Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The Devil's Hole pupfish is often described, perhaps rightly, as “the rarest fish on the planet.” The fish grow to be about an inch long, are sapphire-blue in color, and have alert, dark eyes. They are found in only two places on Earth. One is the real, or at least the original, Devil's Hole, a pool of crystal-clear, geothermally heated water located at the bottom of a limestone cave in the Mojave Desert. The other is the fake Devil's Hole, a pool of very clear, artificially heated water located inside a large barn-like structure, also in the Mojave. The fake pool was designed to closely replicate the top twenty feet of the real thing, including the contours of its walls, which are made not of stone but of plastic foam sealed with fiberglass.

The fake Devil's Hole was created by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service after the real pool's population of toothfish had dwindled to just thirty-five individuals in 2013. The idea was to create a reserve population to prevent the species from going extinct. When I visited both pools a few years ago, the real pool had more fish than the fake. That has now changed, however: The fake Devil's Hole has more toothfish than the real thing.

Theme park “Italy in miniature”, Italy.

While reading Zed Nelson’s new book, The Anthropocene Illusion, I often thought of the toothfish and their two tanks. Nelson is a London-based photographer known for his previous work, including Gun Nation, which explored America’s dangerous embrace of firearms, and Love Me, which examined the beauty industry. For his latest volume, Nelson traveled to fourteen countries to explore our increasingly complex relationship with what we might once have called nature.

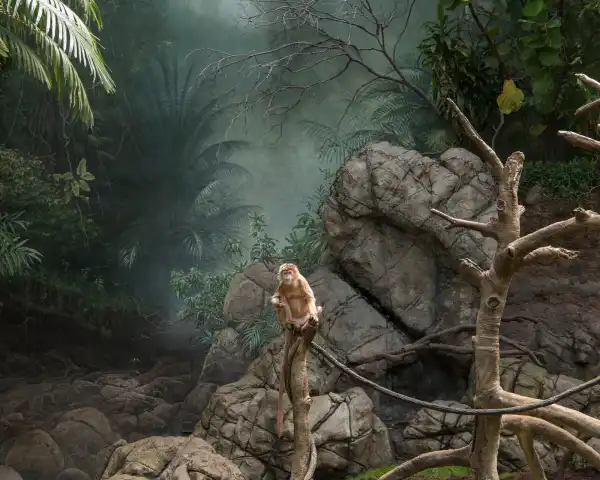

Bronx Zoo, USA

Facsimiles take center stage. In “I

Sourse: newyorker.com