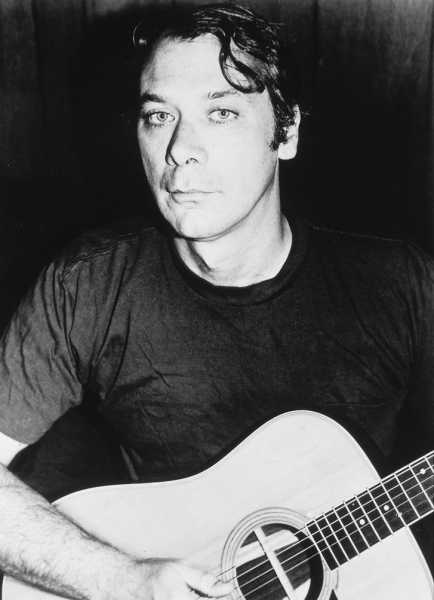

In the fifties and sixties, guitarist John Fahey for the first time a kind of style fingerpicking-called American primitive.

Photo by GAB Archive / Redferns / Getty

This weekend, in Tacoma Park, Maryland, will be one thousand incarnations of the Rose, the first and only festival dedicated exclusively to American primitive guitar music. Takoma Park, a suburb of Washington, D.C., is also the hometown of guitarist John Fahey, who in the nineteen fifties and sixties, made it possible to develop specific and unique style fingerpicking that borrowed from country-Blues—dying music, but Fahey esteemed, possessed—including prickly, dissonant elements more characteristic of avant-garde composers. American primitive is mostly instrumental, and solo, steel-string guitar player working in open tuning. The feeling is introspective, if not clear melancholic—like watching flat water.

Fahey took cues from their ancestors (Elizabeth Cotten, Lena Hughes, Mississippi John hurt), but his sadness was enormous and his own. She forced him to write dozens of albums a strange but exciting songs. Critic Byron Coley, writing in the back, once likened the music of the inventions of Fahey, to “those of John Coltrane and Harry Partch for pure transcendental American power.” Essayist John Jeremiah Sullivan described his songs as “harmonic chambers in which different dead styles were saying to each other”. Fahey, who was famously feisty—it’s been said that in recent years he has become increasingly bitter and choleric, as all people who know too much about things nobody cares about, explained it as an expression of his truth: “the pathos of the suburbs or any other.”

Fahey died in 2001, at the age of sixty-one, after undergoing a sextuple coronary bypass. He had a heart condition, and several decades of predatory for him to drink. He rents a room in the “salvation army” in Salem, Oregon, eating gas station hot dogs for dinner, and sometimes laying your guitar for cash. I wonder what it would be like to spend time with him. I’m pretty sure he would have found me suspicious—lover and a nerd—but I like to think that I could win it in a minute or three, negotiate temporary access to all that is wild and intricate knowledge, which he wore. Fahey was repulsed claims, but he was an intellectual, however, with M. A. in folklore from the University of California (his field work included the discovery and cultural resuscitation Bukka white and Skip James, two titans of the pre-war Blues.) For some time, he knew more than anyone about the music of Charlie Patton. I find my own work Fahey scary and expensive. His songs make me feel closer to something, but, somehow, farther away.

The weekend of the festival coincides with the name of the compilation is guitarist Glenn Jones, who will perform together with a handful of the formation of the American primitive players (Max Baumann, Harry Taussig, Peter lang) and the modern translators (Nathan Bowles, Daniel Bachman, Itasca, Marisa Anderson, Dylan Golden Aycock, Sarah Louise, and many more). In the booklet to “the thousand incarnations of the Rose: an American primitive guitar and banjo, 1963-1974,” Jones is trying to figure out the Name of a genre that never made much sense. Basically, this phrase was for Fahey to avoid being called a folk guitarist, the names of places that he found offensive. It seems to me that it is considered in the contemporary folk as corny somehow too heavy and not heavy enough. (He and his accomplices used to make fun of long-haired folk guitarists crowding the parks of Berkeley in the late sixties.) Eugene Denson, owner and Manager in Tacoma records, the label Fahey founded in 1959, suspects that he may have been the first to use the term, a reference to the self-taught artists of the eighteenth to the twentieth century, and their gnarled, twisted leaf. Of course, “primitive”, with all its Eurocentric connotations, it’s very hard to say, “I have learned to do it myself.” In addition, popular music (in the twentieth century, at least) is not particularly valued or motivated virtuosity, making the difference seem odd. But there is, nevertheless, the scrappiness and the imbalance in the spiritual discord that makes it difficult to follow.

Steve Lowenthal, Fahey great biographer—his “dance of death: the life of John Fahey, American guitarist” was released in paperback this month—understands Fahey music “as the style, his musical influences, but also the time and places where he lived.” While Fahey may be a magician—in the sixties, he was accepted as blind Joe death, staggering to the stage in sunglasses and pretending to be a decrepit sharecropper, deftly mocks the authenticity-obsessed urban revivalists—Leventhal finds his work close and direct. “It seems almost reading a diary,” he told me recently.

“It’s always difficult to pin down Fahey, as it was very opposite, and his thoughts reflect his mood, which wavered,” said Leventhal. “Fahey always wanted to be a composer. In fact, he wanted his unit records were released in the classic series, not the people’s directory. That being said, Fahey lack the discipline or skill to learn to read and write music, insuring its exclusion from this particular Canon. Maybe he used an American primitive in a few frowned, a self-deprecating way that was very revealing of his personality many times”.

Two independent labels from the new American primitive guitarists—Lowenthal for VDSQ and Tompkins square, run by Josh Rosenthal will present their lists in Takoma Park. “The idea of the festival dedicated to the American primitive guitar almost paradoxically, because the music is so inside,” said Rosenthal. “Solo acoustic guitar comes to me better when I’m alone in contemplation, or simply zoning is greatly enhanced due to bad weather on the street. It’s not a very common thing, so the festival should be an interesting experiment.”

Director and guitarist Jesse Sheppard-one of the organizers of the event. “The music scene behind us of the primitive is really quite small, and it can feel like a big family,” said Sheppard recently. “I thought it would be nice to get everyone together—players, loyal listeners, writers, people who run small labels and just enjoy each other’s company. For many reasons and for no reason in particular, no one has ever put this many guitar-solo artists at one event, as far as I know.”

“This music was a huge part of my life for more than ten years,” continued Sheppard. “I don’t think I ever heard anything else that was honest or memories, as an American primitive. Fahey took the guitar and all its rich history of Blues and folk music forms, and then released it to be purely expressive tool.”

Tom Fahey would have received pleasure from his minions have befallen his hometown to contemplate and to honor his legacy is, of course, difficult to say. When Fahey was a student at the American University, he got a job as a night Manager at Martin’s Esso station in Takoma Park. He pumped gas, chatted with cops, and watched quarts of oil. “I have become a very important person for once in my life. I still dream about it,” said Cowley, in 2001, just months before his death. This weekend, at least it will be again—how important the Ghost and inspiration, Enigma and foil.

Sourse: newyorker.com