Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

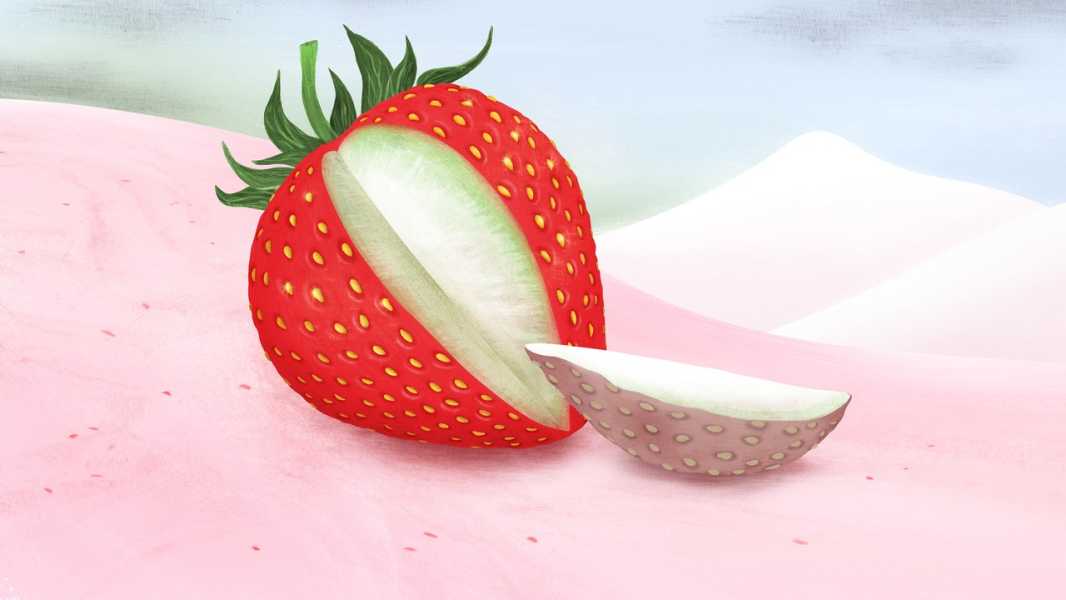

Who among us hasn’t been catfished by a strawberry? At a farmers’ market recently, I bought a carton of strawberries that were vermillion, fragrant, and totally bland. I thought I was just unlucky the first time around, so I bought a second carton further down the road: deep crimson, muffin-topped little berries with an acidity that made me wince. A video has been doing the rounds on TikTok recently—an exposé in which a promising-looking specimen is cut in half and revealed to be watery-white inside. When you see a high-saturation, understatedly bulbous strawberry, a vestige of foraging instinct will tell you that this is the good stuff, but you still might be wrong: a strawberry can check every visual marker of quality and still turn out to be a dud.

Some writers have recommended venturing into nature to find better fruit: Edna Lewis suggested earmarking a patch of good wild strawberries and coming back each year in pursuit of that original high. But Alexis Nikole Nelson, who goes by the alias BlackForager online, warns that the fraud can run deep even in the great outdoors. In a video posted during last year’s strawberry season, she ran a P.S.A. about mock strawberries—a doppelgänger fruit that belongs to a totally different genus. Mock-strawberry seeds cling to the outside of the fruit rather than tucking into little dimples, she explains, and the calyx—that corona of leaves—is more ornate. “Mock strawberries are edible,” she concedes, “but they taste like cucumber water.” Unfortunately, you can say the same for the real ones, a lot of the time.

All fruit has the potential to disappoint—Ralph Waldo Emerson supposedly said, “There are only ten minutes in the life of a pear when it is perfect to eat”—but there’s something especially disheartening about a bad strawberry. In the U.K., where I live, they’re among the most hotly anticipated agri-drops of the year, along with forced rhubarb in February, and the first slender asparagus in April, so we tend to lose our heads when the season finally hits. Almost two million strawberries are sold annually during Wimbledon. A cup of strawberries with molten chocolate, from London’s Borough Market, has been the most enduring viral food I’ve seen in the U.K. (It costs in the region of eight pounds.) Now that we’re nearing the end of peak strawberry season, I’m ready to face the fact that strawberries are routinely the worst investments I make all year. I still do it, though, because the gamble is at least part of the appeal. I got into Yahtzee at the beginning of this year’s strawberry season, and the odds feel the same.

As a dreamer, I’m egged on by the food writers I admire. In the early-twentieth-century fruit fancier’s bible “The Anatomy of Dessert,” Edward Bunyard makes loving note of more than a dozen varieties of strawberry. There’s the corpulent, burgundy-colored Waterloo—“rather too carnal in appearance for vegetarians”—or the large, juicy Louis Gauthier. Jane Grigson, the beloved British cookery author, wrote about strawberries’ fairy-tale cameo in the stories of the Brothers Grimm: once upon a time, a girl banished by a wicked stepmother found small heart-shaped berries in the snow. It’s hard to reconcile romance with reality. It’s been so long since I had a good strawberry that my hazy memory has it tasting something like a strawberry Starburst.

The trouble is that, like a lot of fruit, strawberries suffer for being good, and this puts the perfect berry in a tree-falling-in-the-forest kind of bind. Berries at peak ripeness rarely make it far from the field before they turn to mush, so they have to be picked before they’ve had a chance to develop their character. In Bunyard’s time, before widespread electric refrigeration, the English gentry were said to have sent lackeys to their country estates for fresh strawberries, brought back to the city that same day while still at the peak of their powers. If it seems like overkill, consider the tart, tight-skinned little things we’ve learned to put up with—fruit that tends to rot, rather than ripen, if you leave it to mature in a bowl.

Nicole Rucker, a chef in Los Angeles and the author of “Dappled: Baking Recipes for Fruit Lovers,” relies on her nose to point her in the right direction. “There’s this fetid odor that happens in really aromatic strawberries,” she explained, as with blue cheese or durian, or the muskier, more barnyardy elements of a truly great perfume. This is another of strawberries’ deceits. “If you buy the strawberries and you leave them in your car, then you go put gas in it, if you open the door and your car smells like hot trash—the strawberries are probably really good.” Commercial varieties of strawberries, which are partly bred for their looks, probably won’t ever reach this level of promising pungency, so Rucker, channelling Edward Bunyard, suggested that I go for the varietal deep cuts. In her own garden, she grows white strawberries that have the funk of a ripe pineapple. She also speaks highly of the Mara des Bois variety, which lean heavily toward eau de trash but taste—Rucker assures me—like the pink strawberry Starburst of my dreams.

Once you’ve got your strawberries, one problem remains: what to do with them. Before they get overrun with cotton-candy filaments of mold, strawberries’ final act of spite is that they aren’t even amenable to being cooked. “Cooking strawberries is a tragedy,” Rucker said. With a fruit like apricots, you can coax the best out by roasting them. A sour blueberry will condescend to become a cobbler, and bananas actually come into their own when you neglect them for long enough to justify making banana bread. A strawberry, on the other hand, will liquefy in protest if you so much as think about introducing it to heat.

The realist’s approach to strawberries takes a mitigatory tack: if the odds are that the fruit will be just O.K., why not make Freda DeKnight’s strawberry pie, in which the berries are cooked with plenty of sugar and given a jellylike body with the addition of tapioca? Rucker’s own pie, which she sells at her Los Angeles bakery, Fat + Flour, casts strawberry in a duet with tart, pink rhubarb, bringing the best out of both fruits. I made a strawberry cake from scratch the other day, leaning into the charms of some very average strawberries. The recipe was thorough, the source reputable, but I did question—half a day later and emotionally barren—whether it wouldn’t have been better to use a box of Duncan Hines.

Anyway, there is a middle path. “The best thing you could possibly do with strawberries is eat them out of hand,” Rucker insists, “and the second best thing is to make them into a strawberry shortcake.” Here in the U.K., our high-impact, low-hassle equivalent is Eton mess—my go-to dessert for strawberries that don’t have what it takes to perform solo, but which I don’t want to give up on altogether. (You’ve lost, not just culinarily but on a soul level, when you give over your strawberries to a smoothie blender.) Eton mess is apocryphally what resulted when some guy got knocked by a ball, or tripped over a dog, or barged into by a snub-nosed Eton schoolboy—whatever version of events you want to believe—and dropped a composed dessert of meringue, strawberries, and cream. Eton mess is to pavlova what Ye’s “Through the Wire” is to the Chaka Khan ballad he samples—chaotic, almost overcrowded, but in a way that brings out the best in those original beats.

When I make it, I bake a quick meringue—the blousy, duvet-like variety that you cook for just half an hour in a hot oven. I whip thick cream with a little salt and sugar, cut strawberries into fork-ready chunks, and macerate them for an hour or so with sugar. Toasting and chopping a few almonds helps, too, for bite. I muddle everything together in a large bowl. The syrupy strawberries mottle the cream rose pink and the meringue becomes polytextural: crisp, crumbly, chewy, and marshmallowy.

The mess is nothing like its cousin the fool—a delicate eddy of compote and cream. A mess is bullish, with the dairy deployed less as an accessory than as a preëmptive strike. Serve your strawberries like this and you’ll never be able to tell if they’re bad, although you won’t really know if they’re exceptional, either. They will, however, taste reliably great, which is about as much as any strawberry fancier can hope for in this economy. Some would say it’s a tragedy to smother the fruit like this, but then someone thought it was a tragedy, too, when that dessert was dropped on the Eton lawn. Sometimes the wisdom of the kitchen is knowing when to admit—and embrace—being beat. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com