The impeachment saga of Bill Clinton, the subject of the second season of “Slow Burn,” the Slate podcast hosted by the Slate staff writer Leon Neyfakh, would seem, at first, to have little in common with Watergate, the subject of its first. They were different kinds of scandal, with vastly different causes, trajectories, and outcomes, and the Clinton impeachment didn’t feel like a slow burn, as Watergate was. January, 1998, when the public first became aware of Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky, felt more like spontaneous combustion, and the fire of scandal and political histrionics raged on for the next thirteen months, through Clinton’s impeachment and acquittal. For “Slow Burn,” the story is a bold and curious choice. In its first season, its audience, presumably largely progressive, could revel in Watergate’s absurdities, and in Richard Nixon’s amusing hubris and short-sightedness, while being reassured, almost subliminally, about our own era. We could hope that the special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, whose workings were mysterious, would ultimately prove to be another slow burn, with a Presidential resignation to follow. Focussing on Bill Clinton’s misdeeds provides no such political comfort. But comfort can’t be all that we seek. And I’m pleased to report that “Slow Burn” Season 2 is, so far—I’ve heard two episodes, the first of which was released today—a riveting listen, narratively fascinating, with relevant and urgent themes. If it’s painful for Democrats, it’s appropriately so.

In 1998, the year the mayhem began, Neyfakh was in middle school. Part of what he seeks in the series, which will comprise eight episodes, is to “get into the minds of people who followed the scandal and talked about it and argued about it,” and to figure out why they reacted as they did. As a “child of Democrats,” Neyfakh says, he “took Clinton’s side and believed sort of vaguely and ambiently that Ken Starr was in the wrong.” This reaction was common among adult Democrats, too, though many were chagrined by Clinton’s behavior. Neyfakh says that he hopes that he felt sympathy for Monica Lewinsky at the time. “But I honestly don’t know if I did,” he says. “A lot of people didn’t.” (That, at least, has changed dramatically, in part because of Lewinsky’s own articulate writing and speaking on the subject.) Neyfakh wants to explore “the ideas that swirled around the Clinton saga—ideas about sex and power and privacy and character,” and to consider whether our attitudes and perspectives have changed. “Are we more enlightened now?” he asks. “Or is there something we’re not appreciating about what it was like to live through this story in real time?”

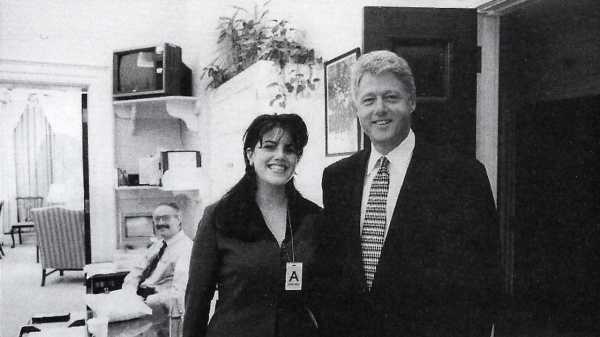

Neyfakh is a gifted and trustworthy storyteller, with a gently wry tone; the details in his writing are lightly comic and well chosen, evincing empathy and amazement. As we meet Lewinsky, it’s January 16, 1998, and she is a twenty-four-year-old former White House intern. (Lewinsky did not participate in the podcast.) She’s waiting to meet a friend from work, Linda Tripp, for lunch in the food court of “a typical suburban mall, brightly lit, with a movie theatre, a Macy’s, and white tiles on the floor,” Neyfakh says. Lewinsky has come from the gym, and she’s still dressed in workout clothes. Her affair with Clinton, which lasted for about eighteen months, consumes her thoughts, and she has confided about the relationship to Tripp. She sees Tripp coming toward her, down an escalator, and Tripp gestures to some men behind her, in dark suits and carrying badges. The men tell Lewinsky that they are F.B.I. agents, “and that the Attorney General of the United States had authorized a criminal investigation into her actions,” Neyfakh says. Then they take her to a nearby Ritz-Carlton, where two men from the office of the independent counsel Ken Starr clarify the stakes: twenty-seven years in prison, for lying on an affidavit in which she denied a relationship with Clinton.

This opening has fascinating parallels to the thrillingly crazy opening scene of “Slow Burn” Season 1, which centered on Martha Mitchell, the wife of the then U.S. Attorney General, John Mitchell, who was in cahoots with Nixon. Each scene tells the story of a woman who is romantically linked to a political figure, held at a fancy hotel against her will, put in a situation of tremendous political import and personal stress, and pressured by powerful, manipulative men. Lewinsky, like Mitchell, resists these pressures.

Neyfakh’s narration captures the often surreal details of political scandal. The agents want Lewinsky to tell them everything about the affair, to coöperate with the Starr investigation, and to participate in an undercover operation to implicate the President. Lewinsky, scared, angry, and upset, wants to wait for her mother, who lives in New York, to arrive before she decides what to do. To pass the hours while they wait, Lewinsky convinces the prosecutors to let her return to the mall, and Lewinsky, an F.B.I. agent, and one of Starr’s investigators proceed to a Crate & Barrel, where they browse the housewares, and Lewinsky tries to “lighten the mood by cracking jokes.” During a restroom trip, Lewinsky, attempting to warn the President, calls Clinton’s secretary’s office from an out-of-view pay phone, but she doesn’t answer. Later, Lewinsky and the agents eat dinner together at a restaurant in the mall called Mozzarella’s American Grill. These are all unexpected moments in an operation that the investigators have named Prom Night.

One of the great strengths of the first season of “Slow Burn” was its deliberate, methodical study of the political Zeitgeist of the seventies. Politics, as ever, was partisan, but behavior in the congressional and judicial branches lacked the extremism and guerrilla tactics of later decades; when the dirty tricks of Nixon’s executive branch came to light, Americans were taken aback. The Clinton era marked a watershed moment for such tactics. “The nineties were a transformative period in American politics, a time when the culture of no-holds-barred partisan warfare that we’re all used to now first took hold in Washington,” Neyfakh says. “January 16th, 1998, represented a turning point in that era. You could argue that it determined everything that happened next.” Beyond the government itself, new, partisan media eagerly fanned the flames of the Clinton conflagration. The Lewinsky story exploded into our consciousness via a new online publication, the Drudge Report; Fox News, which went on the air in 1996, had a field day with it, and with the Clintons more broadly. We haven’t heard much about Fox yet on “Slow Burn,” but we do hear the newscasters of that era, including a recurring Tom Brokaw, who seems to be scolding Clinton at every turn. Brokaw, an anchorman-hero whose beloved book “The Greatest Generation” also came out in 1998, was recently accused of having engaged in work-related sexual harassment, including in the nineties. Brokaw vehemently denied the allegations, and many network colleagues, including Rachel Maddow and Andrea Mitchell, signed a letter of support. The claims, like many of the #MeToo revelations, became a matter of public debate years after the alleged behavior, and it took almost two decades for public opinion to turn in Lewinsky’s favor. Are we more enlightened now? It’s tough to say. Enlightenment is a slow burn, too.

Sourse: newyorker.com