I had the pleasure of visiting Siena in August, though I missed the celebrated Palio horserace that takes place in the middle of that month. Like its historic rival Florence, the city is located in Tuscany but, unlike Florence, had to overcome the major disadvantage of not being served by a river. The city was at the height of its prosperity when the Black Death first struck in 1348, and the plague’s long-term impact was particularly severe there. The magnificent urban core that tourists visit nowadays remains essentially medieval in its layout.

When I wrote about the dimensional impulse in Western design months ago, I did not discuss urbanism. So we should take a look at the urbanism of Siena, where this impulse has been very fruitful.

Advertisement

The Loggia della Mercanzia. The arched structure was originally

completed during the 15th century; the upper story dates to the 17th.

Credit: Catesby Leigh

Pictorial values in urbanism are typified by straight streets receding in perspective to their vanishing point on the horizon as well as linear axes (streets, avenues or malls) terminated by institutional buildings or monuments. Dimensional values are evident in streets that curve or are otherwise inflected so as to suggest uninterrupted spatial continuity. The latter values are experienced on old Siena’s narrow, winding, automobile-unfriendly streets.

On a major thoroughfare, the Via di Città, the curving, continuous space is shaped, at one node, by the august façade of the medieval palazzo that is now home to the Accademia Musicale Chigiana. This façade—with its lower portion built of grey stone and upper levels, including the battlements, featuring Siena’s classic red brick—has a more dynamic space-shaping role than a straight façade would. Such continuity is elsewhere punctuated by the gorgeous white-marble, sculpturally enriched Loggia della Mercanzia, originally appended to a merchant guild’s headquarters during the 15th century. The loggia is located at the junction where two streets merge into the Via di Città.

Siena’s physical development was strictly regulated, but there is no sign of the gridiron template variously employed in the planning of ancient Roman towns and modern American cities. The Sienese instead exploited the contours of the city’s hilly topography and sought maximum benefit from sunlight during the chilly Tuscan winter while limiting the impact of the season’s frigid winds. The endearing spatial qualities of the streets that resulted from this approach could hardly have escaped the public’s attention.

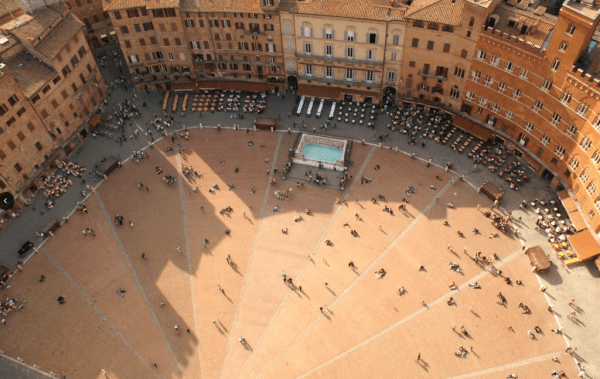

The majestic Piazza del Campo—site of the Palazzo Pubblico and its adjoining Torre del Mangia (1348), as well as the two Palio races held each summer—itself steers well clear of a tidily Cartesian geometric layout. But it was carefully planned and unquestionably ranks among the world’s finest urban spaces. Shaped like a somewhat asymmetrical open fan, it is a gently sloped, concave enclosure.

Advertisement

The Palazzo Pubblico runs along the fan’s base, but its frontage cants inward, toward the piazza, at each end. It is the dominant edifice, faced by buildings mostly designed in a low-key Gothic idiom running along the arc of the fan. The piazza is paved with herringbone-patterned wedges of brick divided by eight travertine bands radiating from an above-ground drain-mouth that features an intricate metal grate with a tangled botanical motif and its shell-work travertine frame. The drain-mouth is situated in front of the Palazzo Pubblico.

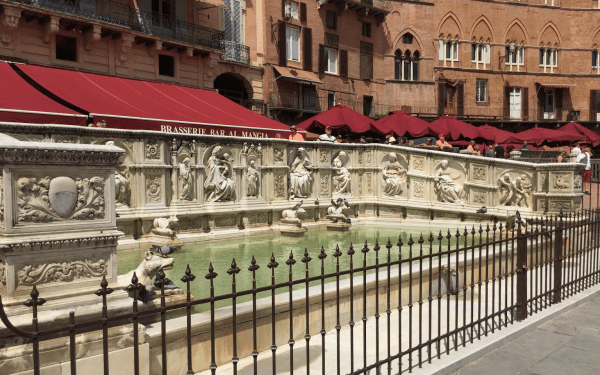

A marvelously elaborate fountain and pool—the Fonte Gaia, originally designed by the sculptor Jacopo della Quercia (1374-1438) and replaced with a copy centuries later—lies at the top of the fan, facing the palazzo. A grey stone pavement that is covered with packed earth for the Palio girds the herringbone fan, which on the race days is crammed with spectators, as the entire piazza—including the buildings looking out on it—morphs into a very crowded stadium, complete with wooden stands. Dashing down the fan’s slope, jockeys—who ride bareback—and their mounts are subjected to a vicious hairpin turn where arc and base meet.

The Fonte Gaia. This replica was completed in 1869, 450 years after

the original fountain. Credit: Catesby Leigh

Only when you enter the Palazzo Pubblico’s stately courtyard, situated at the building’s westerly end, do you experience an open-air enclosure that is geometrically rectilinear. The treeless piazza outside—I actually don’t recall encountering any trees on this commentary’s itinerary—is by no means devoid of formality and conveys a remarkable sense of enclosure. But the contrast between it and the intimate courtyard space registers powerfully, as it was designed to. The Torre del Mangia can be seen looming above one corner of the courtyard. It is the tallest municipal tower in Italy, and it is also taller than the campanile of Siena’s great cathedral, or Duomo, which was mainly completed in 1264. But the cathedral is a far more richly decorated structure than the Palazzo Pubblico and its tower. Combining Romanesque and Gothic stylistic motifs, it is famous for its horizontal bands of white and black marble and profusely sculpted southwest-facing entrance front on the Piazza del Duomo. The palazzo is largely built of humble brick.

The main approach to the cathedral is from the southeast—along the Via del Capitano. This is not a straight street, with the cathedral front terminating an axial vista, as the U.S. Capitol and Lincoln Memorial terminate the National Mall’s main axis. The slightly concave northerly architectural frontage along the Via del Capitano thus flares inward, away from the Duomo’s front, just before ending at the Piazza del Duomo. Instead of gradually looming larger as one makes an axial approach, the cathedral’s entrance façade makes a sudden dramatic appearance. You walk into the piazza viewing the Duomo from an oblique angle that reveals it in all its spatial majesty in a way a frontal, picture-plane vista never could. The Via del Capitano approach was presumably intended to deflect winds blowing through the piazza. Even so, it is a superb example of dimensional urbanism and a more plastic conception of urban space than the gridiron typically accommodates.

The Via del Capitano’s termination at the Piazza del Duomo. Credit: Catesby Leigh

Opposite the cathedral runs the long elevation of a medieval building that was once a hospital but is now home to two museums. At one end, this building’s frontage inflects toward the curia metropolitana, or archbishop’s seat, situated alongside the cathedral. The old hospital building is seemingly pulled toward the curia, whose lower level features the cathedral’s black-and-white masonry treatment, by a gravitational force. The hospital’s configuration suggestively wraps the viewer’s sightline around the curia, while creating a dynamic rather than static relationship between the two structures.

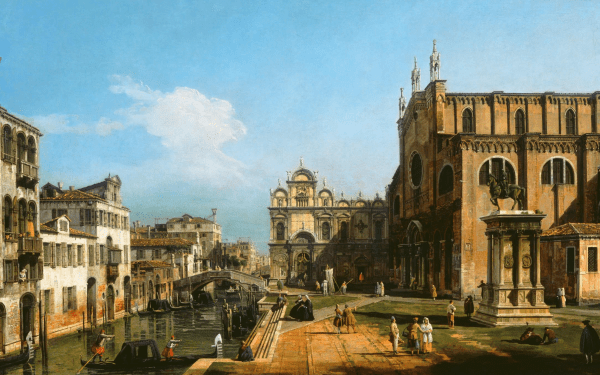

Bernardo Bellotto, The Campo di SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice (ca. 1745). Credit: Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Sophisticated landscape painters of the baroque period were aware of this spatial quality in medieval urbanism as well as in rural landscapes. (This is something I have learned about, along with other aspects of dimensionally-oriented fine art, from Baltimore sculptor Brad Parker.) In the National Gallery of Art in Washington, there is an excellent painting of a Venetian cityscape by Canaletto’s distinguished pupil Bernardo Bellotto (1722-1780). In the background you can see the continuous residential frontage curving along a canal’s trajectory. Bellotto chose this vista in part because that curvaceously continuous spatial corridor enriches his composition. The same principle is at work in the landscape paintings of Meindert Hobbema cited in my aforementioned essay on the dimensional impulse.

Are there any echoes of the urbanism that shaped Siena in these United States? Not many, though we will have to talk about what the New Urbanists might have learned from it and other medieval cities, and from postwar suburbia’s comparatively lifeless winding lanes, some other time. Interestingly, however, Siena’s remote origins lie in three hillside villages—with the site of the Piazza del Campo eventually serving as their nexus—whereas Boston’s early settlers, who were themselves raised in still-medieval English settings, referred to its site as Trimountaine, or three mountains.

Columbian Life Insurance Building. Parker, Thomas & Rice Architects. View down Arch Street in downtown Boston. Credit: Catesby Leigh Subscribe Today Get weekly emails in your inbox Email Address:

Though little is left of those eminences we still find traces of an old urbanism guided largely by topographical considerations in Boston’s downtown. That would be my take, at any rate, on Arch Street where its inflection at the corner of Franklin Street is now beautifully framed by the Columbian Life Insurance Building (1912). Unfortunately, downtown Boston’s historic fine-grained urbanism has been ravaged by postwar redevelopment, which has yielded a number of aesthetically anorexic corporate skyscrapers along with the miserable Government Center complex. Gone, for example, is almost all of the charmingly bent or curvaceous architectural frontage that once lined Cornhill and Brattle Streets. Brattle Street itself is no more.

It’s enough to make a Sienese weep.

This New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. Follow New Urbs on Twitter for a feed dedicated to TAC’s coverage of cities, urbanism, and place.

Advertisement

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com