This year, in celebration of Father’s Day, I figured I’d get my media critic on and take a look at how the small screen has portrayed our proud papas and the institution of fatherhood. From the conservative ’50s to the swinging ’70s to the morning-in-America ‘80s to today, the way that dads were reflected in the media’s magic mirror gave those of us who were fortunate enough to have great dads at home something to compare notes with—and those of us who didn’t something to shoot for.

I’m hardly the first writer (of either gender) to point out that there was a slight irony to classic family sitcoms like Make Room for Daddy and Father Knows Best. Not that the dads were dummies, but usually it was Mother (and sometimes the kids themselves) who “knew best.” One TV reference book notes that The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet was kind of an in-joke itself; though it wasn’t a bad show for its day, it would be hard to think of a show less “adventuresome” than that.

Yet for all their plastic artificiality and unintentional camp (Mom vacuuming and cooking in gowns and pearls), the sitcoms of the ‘50s and early ‘60s epitomized the wholesome return to “normalcy” that the postwar era was about. They represented the ideal, the norm, for dads who uncomplainingly (for the most part anyway) supported their families, showed genuine care and concern for their kids, and were always there to throw a ball or help solve a problem.

As the 1960s unfurled, the family-household sitcoms of the later ‘50s gave way to fantasy shows (Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, The Flying Nun) and the CBS country-and-western rural sitcoms. Sheriff Andy Taylor still has championship status among the pantheon of TV dads, and Jed Clampett was the voice of reason (as much as reason ever entered the picture) on The Beverly Hillbillies. The decade’s highest-rated Western starred Lorne Greene as one of TV’s most iconic dads of all—Big Joe Cartwright, who balanced being tough and demanding with love and loyalty for almost 14 years on Bonanza.

- Roseanne’s Profound Ingratitude

- Boomer and Silent-Gen Fathers Sometimes Fell Short

Happily wholesome family sitcoms still had a strong presence—My Three Sons was a top-20 show for most of the decade (it ran until 1972), and the ‘60s ended with the launch of two of the most iconic family sitcoms of them all, The Partridge Family and The Brady Bunch. If ever there was an iconic TV dad for the early ‘70s, it was lovable Mike Brady, with his even temper, groovy threads and hair, and Have a Nice Day attitude. Yet one of the reasons the Bradys probably attained such iconic status in endless reruns was that they were the last relatively intact and supportive family in TV sitcomhood for nearly a decade.

As David Frum notes in his book on the ‘70s, How We Got Here, the TV sitcoms that ruled the ratings roost in the “liberated singles” era were the ones where children suddenly disappeared from the screen. Mary Tyler Moore, That Girl, Rhoda, Laverne & Shirley, and Jack, Janet, and Chrissy on Three’s Company didn’t have small children underfoot; nor did the crews driving the Taxi, nor the ones rocking and rolling over at WKRP. Hawkeye Pierce of M*A*S*H had kids back home whom he missed, though he was busy saving lives in Korea, just as Barney Miller’s home and family were mostly offscreen.

Once again, the pseudo-Western came riding to the rescue, as Bonanza costar Michael Landon promoted himself from youngest Cartwright son to paterfamilias of the Ingalls clan on Little House on the Prairie, alongside his Depression-era counterpart John Walton Sr. on The Waltons. In more contemporary late-’70s settings, Dick Van Patten’s Tom Bradford had Eight kids of varying ages before he said Enough; James Broderick (the real-life father of Matthew) oversaw the Lawrence family on Family; and Don Murray gave the male moral center to the early days of Knots Landing as Karen’s first husband: kind and fair Sid Fairgate.

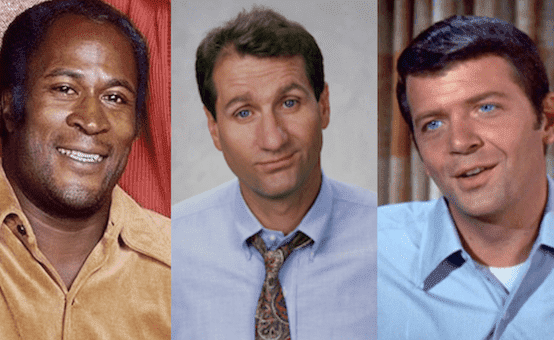

One of the ugliest moments of TV fatherhood in this era came not onscreen but off, when Good Times was in pre-pre production. CBS executives told Norman Lear there was “nothing funny about a strong Black man” and insisted that Florida Evans be a widow or divorced, so as not to have anyone as “threatening” as a mature black male anchoring a sitcom. Lear held his ground. By the show’s premiere in early 1974, there had never been an intact African-American family on regular primetime TV. Alas, as fans of the show know, star John Amos asked to be written out after differing with the direction the network was taking the show. His character was, of course, promptly killed off in the third season. While well-meaning white fathers would care for black children on Diff’rent Strokes and Webster, it wasn’t until Cosby that an intact black family was shown again on the small screen.

But no look at 1970s TV fatherhood could be complete without focusing on the family—All in the Family that is—and perhaps the most iconic small-screen character of all, Archibald J. Bunker. Regardless of whether you swore at or swore by Archie’s ballistically un-PC outlook on life, the reason the character worked for 13 years was because Carroll O’Connor played him with a sense of dusty dignity and working-class honor. As much as he abhorred his “commie pinko” son-in-law’s hippie politics, Archie still supported “Meathead” and the rest of his family on his longshoreman’s paycheck. As ornery as he could be as king of his castle, he clearly loved his “dingbat” wife Edith and “little goil” Gloria, and as the series wore on, his grandson Joey and his niece Stephanie.

Father/son dynamics were also at the heart of the equally long-running Dallas. First was the prodigal son conflict between the two dominant Ewing brothers. It was clear that evil brother JR worshiped his tough-as-nails daddy Jock and built up Jock’s oil company by leaps and bounds. It was also more subtly clear that while Jock might well have favored JR as a businessman, he just plain liked and indulged his handsomer, younger, friendlier son Bobby more. And as diabolically cruel as he could be to the women and business adversaries in his life, one of JR’s few positive values was that he would have done anything for his little boy John-Ross.

This template, of showing a (deeply) flawed anti-hero father who sometimes did horrible things in life but came through for his kids in the end—and of using this to redeem the character in the eyes of the audience—would survive through Tony Soprano, Jack Bauer, and Walter White. (It was also true on the big screen, via Vito and Michael Corleone, just as Archie Bunker had a big-screen counterpart in Robert Duvall’s iconic The Great Santini.)

By the mid-‘80s—with Steven Keaton of Family Ties, Jason Seaver of Growing Pains, Tony Micelli of Who’s the Boss, and Cliff Huxtable of The Cosby Show riding high—the traditional loving TV dad seemed to be making a comeback. But for every action, there was an equal and opposite reaction. When the pilot for Married with Children was first written, the working title was “NOT the Cosby Show.” The Bundy bunch and the (Roseanne) Connor clan were conceived as very purposeful smackdowns and satires of the oh-so-wholesome “family values” sitcoms of the past, as well as their contemporary idealizations in “Cosby,” “Family Ties,” and “Growing Pains.”

There were still lovable and loving TV dads on the ABC “TGIF” lineup of Full House, Family Matters, Step By Step, and on ABC’s other top-rater Home Improvement. (For more adult-oriented TV, Michael Steadman was the least selfish and most caring member of the Thirtysomething main characters, although that’s hardly a high bar to clear.) And everybody loved Raymond on CBS from 1996 to 2005 (and in endless reruns since).

That brings us almost to now. Easily the best TV dad on the current small screen is the late but very much alive (in flashbacks) Jack Pearson of This Is Us. While This is Us might seem hopelessly PC and virtue-signaling to some conservatives, it’s worth considering that Papa Pearson is probably one of the best portraits of a truly “compassionate conservative” ever put on modern primetime TV.

Consider: he overcame a hardscrabble upbringing, served in Vietnam, and then shruggingly went back to his blue-collar, football-and-beer, right-out-of-a-Bruce-Springsteen-song hometown. Jack lived to a Texas “T” the Jordan Peterson ethic of cleaning-your-room and setting your own house in order before trying to change the world, without complaining or playing the blame game. True, he may have spent the ‘70s doing the drinking, drugs, and singles bar thing. But while other Boomers were “finding themselves” by getting divorced and going to group therapy, Jack found his true calling when he watched his young wife giving birth to his family, while Uncle Walter Cronkite beamed down from the hospital TV above.

And in the years when Gordon Gekko was reminding people that “greed was good,” Papa Pearson felt like celebrating when he could afford to get his wife something as simple as a Lady Kenmore washer and dryer or a wood-paneled Jeep Wagoneer. (Or even, fatefully enough, a neighbor’s old slow-cooker.) For a modern-day primetime show, really, does it get more conservative or family values than that?

As we wrap up our look back at TV dads, don’t forget to celebrate the real ones in your life. And if they’re gone (but hopefully not forgotten) or if your own dad wasn’t exactly one to celebrate, then perhaps there might be some Father’s Day binge watching for you to enjoy.

Telly Davidson is the author of a new book, Culture War: How the 90’s Made Us Who We Are Today (Like it Or Not). He has written on culture for ATTN, FrumForum, All About Jazz, FilmStew, and Guitar Player, and worked on the Emmy-nominated PBS series “Pioneers of Television.”

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com