Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

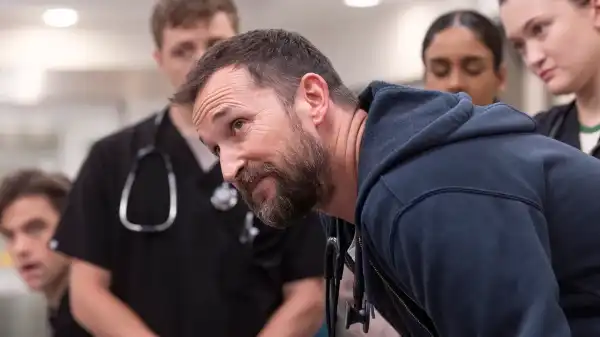

At first glance, the emergency room at Pittsburgh Trauma Center is the backdrop for Max’s new drama Pitt, and it’s the kind of place you wouldn’t send your worst enemy to. The waiting room is packed by 7 a.m., and the wait to see a doctor can stretch into the 12 hours. Rats scurry through the hallways, occasionally getting caught in the folds of one homeless man’s clothing. A long night shift brings one doctor to the edge of the hospital’s roof, where his coworker Michael Robinavich (ER veteran Noah Wyle), known on the department as Dr. Robbie, calls him on camaraderie: “If you’re snaking my shift, it’s just plain rude, man.” It’s an exchange that happens just minutes into the pilot and feels routine. “Pitt,” as Dr. Robbie calls the ER, is short-staffed, staff are being assaulted by patients, and exterminators aren’t expected to arrive until next week. Reviews show that only eight percent of patients who come through the department are “very satisfied” with the care they receive.

In practice, though, Pitt is exactly what you want for compelling, if illogical, television. The plot is simple: It’s ER meets 24, with each episode covering an hour at the hospital, beginning when Dr. Robbie starts his shift. The 15-episode season covers one long, difficult day in his life — the fourth anniversary of the death of his mentor on the same ward. It’s also the first day on the job for a group of young, fresh-faced doctors. With such a large cast made up mostly of strangers and a constant stream of cases and crises, the show’s pacing is disorienting, almost frantic. Forget about lunch breaks; Dr. Robbie can’t even take a bathroom break without facing a code red. Yet the show also relies on nostalgia and predictability. It’s designed in such a way that you know your heart will be broken and mended several times per episode — the only question is how.

It’s probably worth coming clean that I’ve never been a fan of medical dramas. Procedurals like House rarely resonate with me, and I’m not swayed by romantic soaps like Grey’s Anatomy. I’m horrified by the trope of treating patients’ suffering as fodder for personal growth, recently satirised in the promising mockumentary St Denis Med. The anti-heroic protagonists that are so common in the genre also put me off; I’ve encountered doctors who are more distant or dismissive than I’d like in real life. My favourite show in this vein is This Is Going to Hurt, a BBC miniseries starring Ben Whishaw as a burnt-out obstetrician, which appealed to me partly because it explored not just patient care but the NHS’s budgetary woes.

Still, I found “Pitt” gripping, even seductive, in its depiction of emergency room doctors not only as dedicated professionals but also as informal social workers. Dr. Robbie’s patient satisfaction ratings may be abysmal, but you’d never know it, even on his worst day. He allows the parents of a college student who died of an accidental fentanyl overdose to come to terms with his loss as gently as possible — even running unnecessary tests — and extends similar gentleness to a pair of adult siblings as they negotiate taking their elderly father off life support. The resident Dr. Robbie most often chastises for disciplining is the one whose instincts most closely resemble his own: Dr. Mohan (Supriya Ganesh), whom he chides for lingering too long on each patient. Her pathology is that she cares too much.

There’s a popular theory that Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, which focuses on sexual assault cases, is popular with viewers because its detectives pursue criminals with a tenacity we know is much rarer in real life. Pitt displays the same old-school heroism. It doesn’t feel out of touch with the darkness of our world; one plotline centers on how anti-abortion laws make it difficult to access health care. But most doctors in this universe have learned to respond to that darkness with supreme compassion. Particularly adept is Dr. McKay (Fiona Dourif), who shares her story of addiction with a patient living on the streets in an attempt to earn her trust. After spending a few extra minutes with a disoriented makeup influencer, Dr. Mohan is able to save a young woman from being falsely diagnosed with schizophrenia—she’s actually suffering from mercury poisoning caused by makeup. The fantasy of hypercompetence here is not just that these doctors reach the right conclusions almost without fail, but that they treat patients as people in need.

Sourse: newyorker.com