Photograph by Interfoto / Alamy

Photograph by Kevin Mazur / Getty for March For Our Lives

Since the mass shooting on Valentine’s Day at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High

School, in Parkland, Florida, in which a former student of the school

killed seventeen students and staff with a legally acquired

semiautomatic rifle, several of the survivors have become veteran

public speakers. At the March for Our Lives, on Saturday, in Washington,

D.C., speaking before thousands of people from a stage that framed the

outline of the Capitol, they delivered remarks at least as articulate as

those generally heard on the Hill. David Hogg gestured with disdain as

he called on his fellow first-time voters to turn out for the midterms

in 2018, and told lawmakers who were funded by the N.R.A. to “get your

résumés ready.” In a moment of unscripted eloquence, Samantha Fuentes, a

senior who was wounded in the attack, was so overcome with

emotion—“Lawmakers and politicians will scream, ‘Guns are not the

issue,’ but can’t look me in the eye,” she said—that she broke off and

vomited behind the podium. The Stoneman Douglas students shared the

stage with several other impressive young people, including Naomi

Wadler, a fifth grader who had previously organized a walkout at her elementary

school, in Alexandria, and who spoke in honor of young black women whose

lives have been taken by gun violence without making headlines; and Yolanda Renee

King, the nine-year-old granddaughter of Martin Luther King, Jr., who

gleefully led the crowd in a chant, “We are going to be a great

generation.”

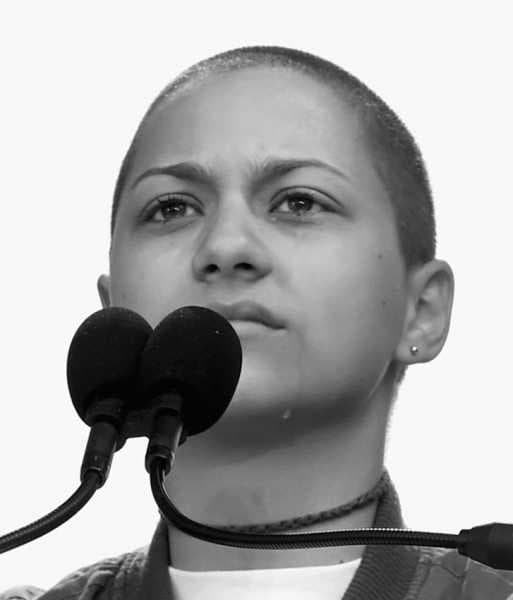

But it was Emma González, a Stoneman Douglas senior, who provided the afternoon’s most memorable moment. Only days after the attack, González

offered a potent combination of composure and fury when she delivered a

speech at an anti-gun rally in Fort Lauderdale, her refrain of “We call

B.S.” swiftly cemented as one of this nascent movement’s slogans. On

Saturday, González, who is small and compact, and who wears her dark

hair cropped close to her skull, spoke for just a couple

of minutes, offering an emotional name-check of the students who had

died. Then, lifting her eyes and staring into the distance before her,

González stood in silence. Inhaling and exhaling deeply—the microphone

caught the susurration, like waves lapping a shoreline—González’s face

was stoic, tragic. Her expression shifted only minutely, but each

shift—her nostrils flaring, or her eyelids batting tightly

closed—registered vast emotion. Tears rolled down her cheeks; she did

not wipe them away. Mostly, the crowd was silent, too, though waves of

cheering support—“Go, Emma!” “We all love you!”—arose momentarily, then

faded away. She stood in this articulate silence for more than twice as

long as she had spoken, until a timer beeped. Six minutes and twenty

seconds were over, she told her audience: the period of time it took

Nikolas Cruz to commit the massacre.

Further Reading

New Yorker writers respond to the Parkland school shooting.

In its restraint, its symbolism, and its palpable emotion, González’s

silence was a remarkable piece of political expression. Her appearance

also offered an uncanny echo of one of the most indelible performances

in the history of cinema: that of Renée Maria Falconetti, who starred in

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s classic silent film from 1928, “The Passion of

Joan of Arc.” Based upon the transcript of Joan of Arc’s trial, in 1431,

Dreyer’s film shows Joan as an otherworldly young woman—she is nineteen,

to the best of her limited knowledge—who, in the face of a barrage of

questioning by hostile, older, powerful clerics, is simultaneously

self-contained and brimming over with emotion. Falconetti, who never

made another movie, gives an extraordinary performance, her face

registering at different moments rapture, fear, defiance, and

transcendence. Joan’s defense in the face of her inquisitors is largely

mute: when she is asked to describe Saint Michael—who, she blasphemously

claims, has appeared to her—she mostly refrains from verbal

response, her silence

bespeaking holy understanding greater than theirs. In the final phase of

her life, when Joan knows that she is to be martyred, Dreyer’s camera

lingers on closeups of Falconetti, with her brutally close-cropped hair,

her rough garments, and her anguished silence. Her extraordinary image

in that sequence could be intercut almost seamlessly with footage from Saturday’s rally.

The consonance is, presumably, accidental: González has said she cut her

hair short because longer hair gave her headaches and made her neck hot,

not because she was aiming to embody a cinematic interpretation of one

of the heroines of history. But the parallel is striking, because

González, with her fervor and her charisma, has already been claimed as

this moment’s Maid of Orléans. “Getting serious Joan of Arc vibes from

Emma Gonzalez,” Summer Brennan, the author, tweeted a couple of weeks ago; Victoria Aveyard, the author of the “Red Queen” series of Y.A. novels, told the Cut the same thing. Meanwhile, González and the other teens and preteens who

have been spurred to action by the atrocity at Parkland are being

heralded as future leaders by former leaders, and former would-be

leaders, at the highest levels. Hillary Clinton tweeted that the march

was “a reminder of what is possible when our future is in the right

hands, and when we match inspiration with determination.” President

Obama tweeted, “Michelle and I are so inspired by all the young people

who made today’s marches happen. Keep at it. You’re leading us forward.”

The desire to cede authority—even if it is only rhetorical authority—to

these young representatives whose passions are not compromised by

practicalities, is understandable: “Naomi Wadler is my President,”

tweeted the actress Tessa Thompson, giving voice to the feelings of

many. In the weeks since the teens of Parkland have become known to the

nation, it’s become conventional to point to the paradox that they are

“the adults in the room,” just as it has become a popular trope to

describe the President, who responded to the demonstrations with a

defensive and uncharacteristic silence, as a big baby, or as a

tyrannical toddler. But such characterizations of the President seem to

me misguided, a slur on the developmental progress of a small individual

through the necessary stages of childhood. Trump’s habitual petulance,

small-mindedness, aggression, self-involvement, entitlement,

mendaciousness, and vanity are not the behaviors of a child. Rather,

they more closely resemble the characteristics of an elderly autocratic

monarch of a feudal realm—King Lear without the poetry. The speakers on

Saturday were, on the other hand, genuinely childlike, in the best

sense of the term: uncompromising, passionate, forward-looking,

fearless.

In the iconography of “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” Joan has authority

not because she is wise but because she is innocent. She has the

privileged knowledge of the inspired, not the earned knowledge of the

experienced. The young people of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School have

already experienced more than their elders would wish upon them; their

innocence is lost. Yet, like all young people, they’ve retained faith in

their generation’s unique ability to challenge and rectify the failures

of their elders. “Maybe the adults have gotten used to saying, ‘It is

what it is,’ but if us students have learned anything, it’s that if you

don’t study you will fail. And in this case, if you actively do nothing,

people continually end up dead, so it’s time to start doing something,”

González said in her speech in Fort Lauderdale, in February. “We’re

going to be the kids you read about in textbooks.” If they muster in

sufficient numbers in November, 2018, it’s not beyond the bounds of

possibility that, unlike most young people, they may be correct in this

assessment. In the meantime, our urgent need for the illumination that

they seem to offer—for the blunt, righteous conviction they uphold—is

another indication, were it needed, that a new kind of medievalism is

upon us. Our potential saviors gleam all the more brightly against the

pervasive political and civic darkness of the moment.

A previous version of this article incorrectly described the weapon used in the Parkland shooting.

Sourse: newyorker.com