Hard to be a Saint in the City: The Spiritual Vision of the Beats by Robert Inchausti, Shambhala (January 30, 2018), 208 pages

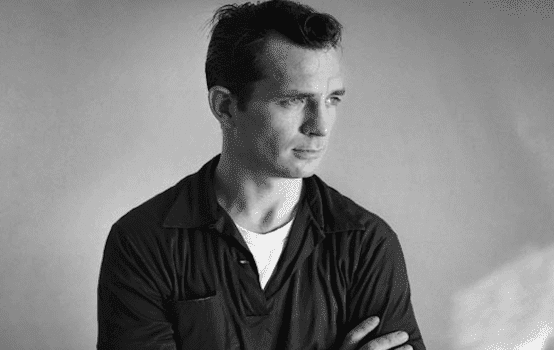

Catholic mystic poet Jean-Louise Kérouac, better known to the American public as “Jack,” was destined to be misunderstood. The spiritually inverted radicals of the Sixties who sacralized their politics and secularized their spirituality—blame Reich and Marcuse—read Kerouac with blinders on. They only saw what they wanted to see, and what they wanted to see was a celebration of the “freedoms” of hedonism. The rootlessness. The veils of marijuana smoke drifting through jazz clubs. The anonymous, sweaty encounters in bohemian apartment buildings decorated with abstract art. Kicks for the sake of kicks. The very definition of nihilism.

The real tragedy of Kerouac’s reception was that the people who should have known better took the en vogue hedonist reading at face value, writing him off as a word-vomiting miscreant. But that’s a caricature of Kerouac that over-emphasizes the most obvious personal flaws of an intensely spiritual writer. It’s an oversimplification by way of calling someone a simpleton. The truth is more complex and so much more interesting: Kerouac was one of the most humble and devoted American religious writers of the 20th century. Robert Inchausti’s recently published Hard to be a Saint in the City: The Spiritual Vision of the Beats makes an attempt at recognizing the heterodox spiritual focus of the entire Beat oeuvre, but it only points the reader in the right direction. Its simple and hodgepodge construction suggests the vast amount of analysis, particularly of Kerouac’s work, which remains to be done in order to change his reputation in the popular imagination.

The charge of mindless hedonism dogs Kerouac despite his wearing his spirituality on his sleeve. In most of his less famous books, such as Visions of Gerard, Dr. Sax, and Tristessa, you can read his influences like a palimpsest. The Romantics, especially Shelley and Keats, are there. The Transcendentalism of Thoreau looms large. But there’s also a deep dedication to the Buddhist vision of the Void and escape from the spinning wheel of Samsara, which was cultivated long before Buddhism became a lifestyle trend among certain American crowds.

Underlying all of this as Kerouac’s spiritual bedrock was his Catholic upbringing in Lowell, Massachusetts among working-class French Canadian immigrants. Kerouac described himself as a “strange solitary Catholic mystic” whose ecstatic vision of life was the direct result of an eschatology of the end of time. What he longed for was contact with the heavenly eternity overlaying and occasionally penetrating our anodyne perceptions of time. “Life is a dream already over,” he said. It was the furthest thing from an existential claim of the primacy of death and absurdity. It was life reinvigorated by recognition of a transcendent reality.

Kerouac wasn’t a hedonist and he wasn’t an Epicurean. However questionable his methods and his theology, he believed that his life had a spiritual purpose. Benedict Giamo explains in Kerouac, the Word and the Way: Prose Artist as Spiritual Quester: “As a modernist mystic, Kerouac believed that direct knowledge of God, spiritual truth, and ultimate reality could be attained through subjective experienced (conceived as intuition or insight). This was both his wager and means for being intoxicated—drunk with life—(helped along, as always, by alcohol and/or drugs). His aim, however, was not to get smashed; rather it was to get a higher purchase on the ecstasy of being in order forge a mystical bond with the divine or ultimate.”

This spiritual focus is what Inchausti tries to emphasize for Kerouac and other Beat writers in Hard to be a Saint in the City, which is a compendium of quotes organized and edited by Inchausti that also includes a very brief introductory essay by Inchausti explaining the project. The thing is a hard sell. For one, as is apparent even from a collection of quotes organized thematically, the Beats were wildly diverse. To even lump them into a single literary or generational movement was, from the beginning, a bit of a marketing ploy. Allen Ginsberg was a Marxist-turned Buddhist anti-nuke gay liberationist poet. William Burroughs had more in common with the Dadaist who preceded him and the punk movement that followed than his fellow Beats. Eco-poet Gary Snyder longs (he’s still alive) for some kind of Native American-Buddhist synthesis. Amiri Baraka was a homophobic Marxist-Leninist.

But even allowing for the amorphousness of the category, some of the choices Inchausti makes are confusing. Including Leonard Cohen suggests a continuity with Sixties pop culture that books like this should do their best to refute or at least complicate. And not including seminal figures like Kenneth Rexroth gives the false impression that the Beats sprang fully formed from Eisenhower’s shadow rather than the messier truth that they represent various strains of American thought and art that have existed since the founding.

The collection of quotes, varying in length and pithiness, are fascinating. Hard to be a Saint reads like a courtroom transcript of The Establishment vs. The Artist, providing expert witness testimony on behalf of the defense. But structured as it is, the book raises questions that it can’t answer. The quotes are mostly taken from interviews, letters, and editorials. But the people being quoted are poets and novelists. Their spirituality is primarily embedded in their art. In order to understand the depth of their spiritual engagement, we need to read their poems and novels. And in order to understand their art in new and different ways, we need the kind of analysis that Inchausti provides in his brief section on Kerouac in 2005’s Subversive Orthodoxy, interpretation which is mostly absent from the present volume.

The most interesting part of Inchausti’s too-brief introductory essay is his mention of Oswald Spengler, the German historian whose cyclical vision of history is probably the only significant common influence between the major figures of the Beat Generation. Inchausti writes:

At the heart of this re-visioning of American letters resides Oswald Spengler’s eccentric, magisterial opus The Decline of the West—a book that greatly influenced both Kerouac and Burroughs and provided the vocabulary and conceptual framework for the very idea of a Beat Generation. Central to Spengler’s thesis is the notion that all cultures begin as “cults”—spiritual enterprises designed to convert that “zoological struggle for survival” into a pursuit of various high ideals…As cultures ag, Spengler observed, they inevitably decline into “civilizations”, which means that the mechanical operation of their institutions come to replace the idealistic zeal that fueled their collective endeavors in the first place.

The decline that Spengler theorized can last a long time, “hundreds and hundreds” of years according to Inchausti, during which underground movements of nascent religious rebirth imbue old symbols with new vitality. “Spengler called these idealistic culture-bearers fellaheen,” Inchausti writes, using a word that originally referred to itinerant Egyptians living on the edges of the Roman Empire, but which a few of the Beats used to describe their own spiritual predicament as artists in an increasingly secular world. Inchausti explains that “Literature was always to be something more than literature, something more akin to scripture” for the contemporary fellaheen.

Of course, for Ginsberg, being fellaheen meant embracing a blend of Whitmanesque sex-worship and a strange Buddhist Utopianism. For Burroughs, it meant a kind of transhumanism in which we leave our species behind and prepare to live in space. Kerouac’s response was different. For him, Spengler’s eschatology was just a secular parallel to his own idiosyncratic (and heterodox) but definitely Christian mysticism. His sensitivity to time and loss and his hunger for eternity moved him to write things such as “All is well, practice kindness, heaven is nigh” in Visions of Gerard and “Practice kindness all day to everybody and you will realize you’re already in heaven now” in his collected letters. And from his novel Tristessa: “I know everything’s alright but I want proof and the Buddhas and the Virgin Marys are there reminding me of the solemn pledge of faith in this harsh and stupid earth where we rage our so-called lives in a sea of worry, meat for Chicagos of Graves—right this minute my very father and my very brother lie side by side in mud in the North and I’m supposed to be smarter than they are—being quick I am dead.”

It’s probably not the best literature you’ll ever read, but that’s because it works differently. Kerouac didn’t want to be Philip Roth. He wanted to be a mid-century jazz version of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz. His unique spiritual vision demands more than what amounts to a coffee table book of quotes can provide. Hard to be a Saint in the City might make an interesting introduction for someone completely unfamiliar with the Beats individually and as a group, but by presenting what could be a rich spiritual and artistic resource completely denuded of context, the book undermines its own premise. It makes the Beats look exactly like what both the longhairs and hardhats took them to be: pioneers of an embarrassingly shallow, self-involved hedonism.

Scott Beauchamp’s work has appeared in the Paris Review, Bookforum, and Public Discourse, among other places. His book Did You Kill Anyone? is forthcoming from Zero Books. He lives in Maine.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com