In recent months, the crisis of immigrant children separated from their parents and held at detention centers has dominated the public imagination. Meanwhile, our understanding of another form of captivity in the U.S.—mass incarceration, including that of juveniles—continues to evolve. “Caught: The Lives of Juvenile Justice,” a nine-episode podcast series from WNYC Studios hosted by Kai Wright, introduces us to some of those kids, who are trying to find their way out of trouble—trouble they got into, and also trouble related to the incarceration itself. Many of those we hear from are black, many are poor, and many struggle with mental-health issues. (And those issues can begin during incarceration, we learn.) On top of all that, many young inmates are dealing with draconian sentences. The series doesn’t shy away from the complexity of the kids—their anxieties, their bad decisions—or from the severity of their crimes. It explores ideas about freedom, control, and what it means to be incarcerated at all. As the podcast puts it, “What happens once we decide a child is a criminal? What does society owe those children, beyond punishment?”

Wright, a columnist for The Nation and a veteran WNYC reporter, whose recent work includes the excellent podcast “There Goes the Neighborhood,” about gentrification, makes for a sharp, sensitive guide. Several reporters contribute to the series; Wright narrates throughout. He appears most prominently in the story that frames the series, which concluded in the spring, about a boy he calls Z. When we meet Z, he is sixteen and incarcerated at a facility in Queens after an armed-robbery conviction. Z talks to his mother in the visiting room, and we hear the love and weariness in her voice. As a kid, she says, he used to wear a Spider-Man costume and sing the “Spider-Man” theme. After he was diagnosed with a learning disability, she bought a dictionary and encouraged him to learn new words and to rap—which he did, composing his own songs at age eight or nine. We hear a clip of one: a young boy’s voice, at once sweet and posturing, rapping “bouncing like a bunny” over and over, and mentioning haters and how he’s “fresh like Jay-Z.” It’s a catchy, gently funny song; hearing it, you feel tenderness toward him. “Now look at you,” his mom says, sadly but without bitterness.

This moment is the kind of masterly detail we hear often in “Caught.”(It makes an excellent companion to other recent work about incarceration, including the Vice documentary “Raised in the System,” hosted by Michael K. Williams, and the podcast “Ear Hustle,” about life in San Quentin.) We get to know Z well in the course of the series, and his frustrating, heartbreaking story is presented alongside a contrasting narrative—that of Reginald Dwayne Betts, who served nine years for carjacking as a teen-ager, in the nineties. Betts is now a poet, memoirist, and juvenile-justice lawyer. Like many of the people profiled in “Caught,” Betts was a kid who impulsively bumbled into a bad choice. He’s “kind of dumbfounded” by it now, he says. Betts didn’t initiate the carjacking; he didn’t even know the names of the kids whose idea it was. (“Caught” is highly attuned to the workings of the teen-age mind, and in one episode explores its neuroscience.) Betts hopes that admitting how little he thought about it beforehand “makes it more obvious how kind of oblivious I was.”

Betts didn’t hurt anybody—he flashed a gun and stole a car. But during his trial the prosecutor called him a “menace to society,” evoking the 1993 Hughes-brothers movie about bored, murderous black teens. The nineties were “a moment when the American imagination became fixated on a particular kind of black masculinity,” Wright says, involving “super-predators” and violent crime. “Tough” sentencing was often a response to this; often, it still is. Betts says that at his sentencing the judge said, “ ‘I am under no illusion that sending you to prison will help.’ And then he sentenced me to nine years in prison.”

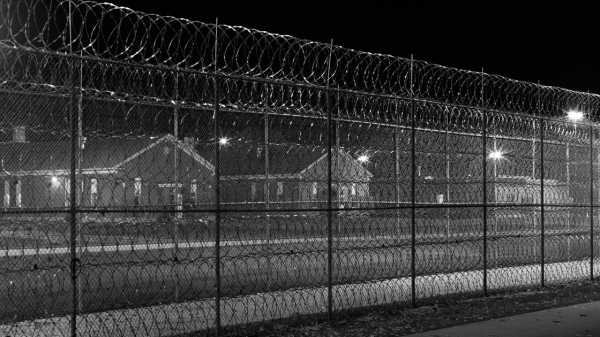

At sixteen, Imani was arrested after being charged with shoplifting at a dollar store. She ended up in an adult prison in New York, where she spent four months in solitary confinement.

Photograph by Alberto Morales / NYCLU

“Caught” navigates its ambitious themes with an approach that’s both focussed and impressively wide-ranging. In Episode 3, it provides historical perspective through the story of Willie Bosket, who, in 1978, at the age of fifteen, murdered two strangers on the subway and shot a third, terrifying much of New York City. Bosket’s case led to the creation, that year, of New York’s Juvenile Offender Act, which allowed minors as young as thirteen to be tried as adults; the other forty-nine U.S. states followed suit. The episode explores attempts to rehabilitate him and the wider consequences that his case—plus politics—brought about. Elsewhere, the show explores a diversion program that serves as an alternative to incarceration; wilderness-therapy programs that, though expensive, can be quite effective; solitary confinement; and female juvenile offenders, who make up a small percentage of incarcerated teens, and for whom sexual abuse is often a key factor. Many of us are aware of the poverty-to-prison pipeline; for girls, we learn, there is also a sexual-abuse-to-prison pipeline.

What makes “Caught” truly stand out is the voices of its subjects. For one thing, the kids sound like kids, which, considering their circumstances, is startling in itself. In their words and tones, many sound lost. Most are honest about their bad choices and emotional struggles. They are still finding their way, discovering who they are, who to trust, how to act. Often, their behavior perplexes them, too. “There’s some people that belong in jail and there’s some people that’s misguided and don’t know what to do,” Z says. He says he’s a mix: “I want to be a good guy but sometimes I’m a bad guy.” Desirée, who’s been in and out of foster care and keeps acting out, knows that she’s difficult. “I’m not going to blame, like—I’m not going to put my trauma to be, like, Oh, that’s an excuse to be bad, or whatever,” she says. “But I’ve been through things—I just want attention, I just want somebody to love me. I don’t care if it’s, like, for a second.”

In that moment, and in many others, “Caught” makes us consider some of the most basic questions about being human and being humane. A young woman called Imani touches on those themes with a grim eloquence. At sixteen, Imani was arrested after being charged with shoplifting at a dollar store; her problems snowballed from there. She ended up in an adult prison in New York, where she spent four months in solitary confinement. No TV, reading, calls, education, talk, or mental-health services. “You just sit there and wait for the next day to come,” Imani says. “It made me feel like nothing. Like a animal. You wake up, they give your a tray through your slot—that’s it.” It changed her in lasting ways. “When you get out, you still feel like a animal sometimes,” she says.

Sourse: newyorker.com