Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

For “The Children’s Melody,” his third collection of photographs, Eli Durst, the lensman, journeyed back to his former grade school in Austin, Texas. The edifice, dating to the New Deal, seemed strikingly untouched, save for the abundance of portable computers. The aroma of the lunchroom was unchanged. One of the teachers from his past was still present, urging pupils to form an orderly line. “It was as though I had become eight years of age once more,” Durst confided.

“Elementary School Audience,” 2023.

“Elementary School Audience,” 2023.

Durst enjoys snapping images of activities—the communal, ordered happenings that exist somewhere between labor and pure leisure. His initial publication, “The Community,” took shape as a project investigating church cellars, later growing to encompass other versatile areas that provided space for theological study circles, along with gatherings of Boy Scouts, team-strengthening activities, and performances by amateur theatre groups. These common American customs, perceived through Durst’s attentive, inquisitive gaze, appear enigmatic, brimming with unforeseen meaning. A group of arms stretches toward a bread roll; a lady, shown from the back, joins hands with a pair of figures. The images underscore the strangeness and occasional ludicrousness inherent within our methods of constructing meaning of ourselves and others.

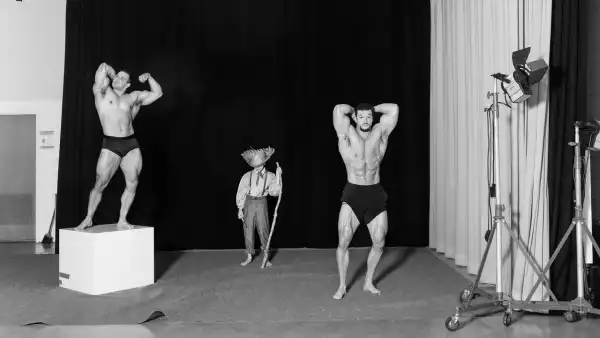

“Props, Texas State History Play,” 2023.

“Props, Texas State History Play,” 2023.

“The Children’s Melody” employs a tighter focus, zooming in on young individuals—typically spanning elementary age to college—as they take part in a spectrum of group activities: R.O.T.C., cotillions, school dramas, cheerleading drills, Irish stepdance. “I’ve felt perpetually drawn toward capturing group undertakings where you find both rehearsal and exhibition. Situations where one is in the process of becoming, of practicing and assimilation, followed by external performance,” revealed Durst. He expresses fascination with “the means by which we absorb mannerisms, gendered expectations, or notions of worth—the ways in which these aspects shape our identities and our subsequent projection of them for others.” The images comprising “The Children’s Melody” were almost exclusively taken within Texas, a locale that, notwithstanding its proclaimed reverence for personal autonomy, is vehemently dedicated to molding its younger generation. The state accounts for over a quarter of the country’s catalogued instances of literary suppression; numerous collegiate networks curtail dialogues on transgender and nonbinary identities; furthermore, a freshly enacted state statute compels the presentation of the Ten Commandments within all state-operated school classrooms. Durst maintains an interest in institutions endeavoring to instruct and exert influence over juveniles, though the resulting pictures are not demonstrations of pure conformity; in “The Children’s Melody,” any form of ideological molding remains consistently conflicted and unresolved.

“Curtain Peek,” 2023.

“Curtain Peek,” 2023. “Irish Dancer,” 2023.

“Irish Dancer,” 2023.

Durst’s sophomore work, “The Four Pillars,” was primarily created in the course of the COVID crisis. Its vaguely theatrical scenes, many centering on a New Age self-improvement group that Durst had observed since his church-basement years, accentuated the awkward superficiality that characterized the era. Undertaking the pictures that comprise “The Children’s Melody” seemed like “stepping back into society,” replete with all its confounding complexities, Durst explained. The concept took firm hold after Durst captured a snapshot of a jubilant assembly of second-grade students singing. The resulting picture displays a casual coordination—various children keep their encircled arms extended, fingertips connected—yet the overarching feeling is one of happy, uninhibited disarray. Children peer to the left, to the right; they vocalize with their eyes shut; they gaze pointedly at each other; they are, quite obviously, lost in daydreams. The picture centers on the challenge of organizing individuals into a collective, the task allotted to our instructors, mentors, and group coordinators. In Durst’s art, such endeavors achieve only partial success. As the collection unfolds, some youngsters within the photos exhibit advanced age and greater command over their external behaviors, yet vestiges of oddity or inconsistency constantly emerge.

“Three Brothers,” 2025.

“Three Brothers,” 2025.

The youths showcased in Durst’s visual narratives experiment with guitars, diadems, military attire, graduation robes, and miniature bow ties, inhabiting these with a fluctuating degree of self-assurance. Some appear perfectly at ease in their adult-like costumes. A young woman in lipstick and a curled blond wig advances confidently, countenance glowing and chest inflated, as if stepping onto an imagined stage bathed in limelight. In other moments, attire seems to magnify feelings of vulnerability: an R.O.T.C. trainee, donned in camouflage gear, glances anxiously past the photograph’s perimeter, seemingly alerted to a threat unseen by the observer. Durst’s images vividly portray the bizarre fluidity of time etched on children’s faces, capturing how they may simultaneously embody aspects of both greater maturity and relative youth.

“Two Couples, Cotillion,” 2025.

“Two Couples, Cotillion,” 2025.

One of the collection’s most arresting visuals is conversely, among its simplest. Four youngsters attired in semi-formal clothing are aligned against a wall. They are of roughly corresponding age—perhaps numbering twelve years—yet exhibit considerable variations in height. The second tallest, a young man, meets the camera with the unwavering gaze reminiscent of a future student-body leader. The tallest, a young lady adorned in a tiered skirt, displays a heightened degree of caution. Their core characteristics are apparent yet remain incompletely realized; the grown individuals they could one day become intermittently materialize, then recede. The snapshot described forms one of several obtained during a cotillion event, a primarily Southern custom involving both etiquette workshops and formal dance training intended for individuals in their middle-school years. Its pronounced theatricality and formality make it a quintessentially suitable subject for Durst. While specific components of cotillion may feel dated (precisely who now needs cha-cha lessons?), Durst’s collection is devoid of cynicism. Cotillion, at its core, embodies the concept of children engaging with one another directly. (My personal reminiscences of cotillion pivot largely around seventh-grade dramas; I’ve since forgotten all the dance steps.) The children remain uncertain as to its meaning for them, and Durst fully embraces their sense of doubt.

“Communion,” 2023.

“Communion,” 2023. “Daisy, Black Eye and Broken Nose,” 2024.

“Daisy, Black Eye and Broken Nose,” 2024. “Praying, Church Youth Group,” 2023.

“Praying, Church Youth Group,” 2023.

Durst employs digital methods, using several off-camera flash devices positioned for strangely subtle effects. The monochrome renderings at times feature backlighting, and at others are illuminated through focused light striking from atypical angles. In one image, a flash makes an appearance within a mirror, manifesting as an eccentric orb and prompting viewers to recall the presence of the individual behind the camera. The environments exhibit both tidiness and the accumulation of time; traces of their dilapidated nature reveal the aggregation of many years, countless children inhabiting these seats, performing specified actions, adhering to established dance patterns. One the collection’s initial images reveals a vacant school theater. A platform traverses the stage, bordered on a single side by Texan and US banners, and on the opposite by a simulated tree in a sizable planter. The curtain is partially opened, providing a hint of a backstage region that escapes the eye. There are performance lights, a microphone, an amplification device. The depicted setting contains nothing surreal, and yet the image is imbued with dreamlike energy, a distinctive form of archetypal power that prompted recollections of how my recurring anxiety-laden dreams revert me to places bearing a distinct likeness to the setting depicted.

“Cheer Pyramid,” 2024.

“Cheer Pyramid,” 2024.

The introductory quotation for “The Children’s Melody” consists of a terse, instructional poem pertaining to children’s activities, penned in the sixteenth century by Henry VIII. The monarch extols the “feats of arms” along with supplementary “good disports” seen as “pleasant to God and man,” a commendable form of busy-ness that suppresses threats associated with “vice.” Feelings of concern over how the young elect to occupy their waking moments represent a recurring pattern among adults, one predating the arrival of Minecraft by an extensive margin. Hardly any instances of digital technology infiltrate Durst’s images. Instead, children perform, compete, and consider one another. They exist within settings defined by brick exteriors, collapsible chairs, dropped ceilings, exposed duct conduits, and fragmented laminate at the base of a split door. A projector rests atop a scuffed desk, supported through a collection of religious texts. The surface of a gymnasium constructed with timber is so polished as to almost transmit the sound of sneaker soles squealing. An absence of time exists across these zones, but the feelings that images trigger are more refined and unsettling than unadulterated nostalgia. “I have memories of experiencing profound anxiety in my youth, experiencing acute nervousness associated with self-understanding,

Sourse: newyorker.com