The big shebang this week is the Met Breuer’s “Like Life: Sculpture,

Color, and the Body,” a sprawling, at times carnivalesque survey of

three-dimensional approaches to the human figure over the past two

thousand years. A few blocks north, at the museum’s Beaux-Arts HQ, there

was a less splashy, but no less momentous, unveiling: the redesign of

the museum’s musical instrument galleries, which have been shuttered for

the past two years. Part of me will miss the former cramped quarters,

which felt like stumbling onto a secret compartment from a quainter

era—some of the labels in the wall-mounted cases were still typewritten

index cards. The new, airy, open-plan installation, in contrast, has

audio and video kiosks. My favorite addition is a dazzling display of

brass instruments (and one conch shell, carved in the Republic of

Vanuatu, in the South Pacific), suspended in midair inside a giant

vitrine, as if they are dancing in space. The sculptural finesse of the

objects—a spindly German brass trumpet in D, designed by Andreas

Naeplaesnigg, in 1790; a coiled horn, clear with red-and-blue stripes,

fashioned by glass blowers in southern Belgium in the nineteenth

century—is undeniable, an invitation to lend music your eyes, as well as

your ears. Are instruments works of art? Consider Kandinsky, who

believed that his paintings could induce us to hear musical chords. He

advised against getting hung up on distinctions between sight and sound,

and wrote, “Just ask yourself whether the work has enabled you to ‘walk

about’ into a hitherto unknown world. If the answer is yes, what more do

you want?” Below are some of our suggestions for your walkabout over the

weekend.

UPTOWN

Allan Kaprow

Kaprow is best known for inventing “happenings,” a term he coined sixty

years ago in the essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock.” But he started

out as a painter, as this museum-quality show makes sensationally clear.

Several mid-fifties views of the George Washington Bridge, portraying

both the bridge and the sky with bars of glowing color, may bring to

mind the early realist work of Piet Mondrian. Two “action collages” from

the same period, incorporating jagged pieces of foil and fabric, are

nearly transcendental in their exuberance. A series of colorful,

vigorously impastoed portraits push against formal limits with strange

cropping. By the nineteen-seventies, Kaprow was making extremely simple

charcoal drawings of lines and circles, inspired by Zen breathing

exercises. The energy of the assembled works is so consistently restless

that it suggests an artist for whom one medium alone would never

suffice. As Kaprow inscribed on the stretcher bars of his canvas

“Standing Nude Against Red and White Stripes,” which he completed in

1955, “I will always be a painter. Of sorts.” Through April 7th. (Hauser

& Wirth, 32 E. 69th St. 212-794-4970.)

“Kiss Off”

Artwork by Francis Picabia. Courtesy ARS / ADAGP / Luxembourg & Dayan

This eighteen-person meditation on a Hallmark-worthy theme (the subject

of kisses in art) steers clear of schmalz, thanks to the smarts of its

curator, Francesco Bonami. It opens with a 1970 lithograph of undulating

red lipstick marks, made by the experimental filmmaker Joyce Wieland

while she sang “O Canada.” The work hangs next to the show’s title

piece, “Kiss Off,” made a year later (in Canada) by Vito Acconci

(1940-2017), who applied lipstick to his mouth, kissed his hand, and

transferred the marks to a lithography stone. The show closes with

another game of compare and contrast. In Francis Picabia’s strange,

brightly colored “Couple de Monstres,” from 1925-27, two lovers embrace.

Nearby, in Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s heartrending untitled sculpture, two

rings of silver-plated brass hang side by side on a wall, so close that

they appear fused together—but, in fact, they’re not touching at all.

Through April 14th. (Luxembourg & Dayan, 64 E. 77th St. 212-452-4646.)

CHELSEA

Barnaby Furnas

The mid-career, Brooklyn-based painter tackles his angst, both aesthetic

and political, by depicting echt American imagery with a custom-designed

arsenal of technologically enhanced sprays, drips, and washes. “Mt.

Rushmore,” with its stained-gray triangles under cloudy streaks of

white, seems to be as much about the construction of a painting as it is

about national monuments. But “The Rally,” in which a generic

Presidential figure behind a zigzagging podium waves to a sea of

upraised hands, while tiny fighter jets strafe his head, makes it clear

that Furnas is deeply concerned with the messy spectacle of America now.

Through April 14th. (Boesky, 509 W. 24th St. 212-680-9889.)

Robert Gober

In the American sculptor’s first New York solo show since his 2014 MOMAretrospective, an abundance of small works mine his familiar, if

mysterious, themes. Barred windows and patches of forest (images that

recall past installations) are nestled inside bare chests in a series of

pencil drawings. Twenty wall-mounted assemblages are nursery-ready nods

to Joseph Cornell, with green apples and blue robins’ eggs suspended

against cloth diapers and floral-patterned wallpaper. Gober’s

idiosyncratic lexicon, drawn in part from childhood memories, lends his

work an eerie lyricism, whatever the medium or scale. The pathos of a

little, sunken cellar door near the start of the show—a

foam-core-and-balsa-wood maquette for a sculpture first exhibited at the

2001 Venice Biennale—gives way to the near-mythic aura of its full-sized

counterpart, which provides the show with its finale. Through April

21st. (Marks, 526 W. 22nd St. 212-243-0200.)

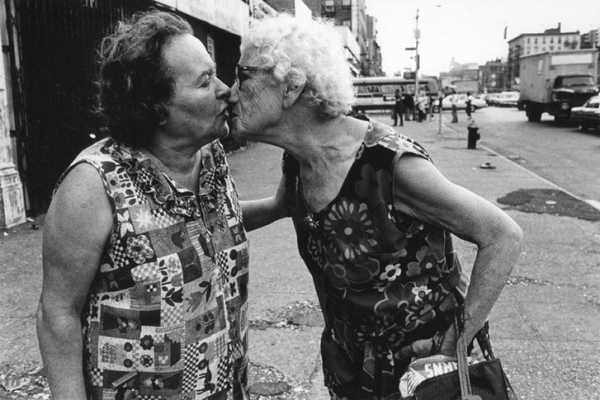

Arlene Gottfried

Photograph by Arlene Gottfried / Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Aptly titled “A Lifetime of Wandering,” this posthumous exhibition of

the photographer’s street scenes and portraits captures New York’s

demimonde of the nineteen-seventies and eighties from a warm and

impromptu perspective. Among Gottfried’s coöperative subjects were

Brooklyn beachgoers, Harlem gospel singers, and disco-era clubbers, as

well as underground icons and international celebrities. A shot of the

transgender activist and performer Marsha P. Johnson shows her posing,

with a wide smile, in the middle of the street. Diana Ross, standing by

a wall and dressed to blend in, likewise beams for the camera.

Gottfried, who died last year at the age of sixty-six, also photographed

those closest to her. One of the show’s high points is “Mommie Kissing

Bubbie on Delancey Street,” from 1979, which celebrates two generations

of her Jewish immigrant family in an unguarded moment on the Lower East

Side. Through April 28th. (Cooney, 508 W. 26th St. 212-255-8158.)

Oliver Laric

Despite the cartoonish friendliness of the young Austrian artist’s drawn

lines, there’s an undeniable melancholy to his new video, “Yet to Be

Titled,” in which animals and people transform in a series of surreal

vignettes. Two hairy male faces, made up of curving dashes, rearrange

into monkeys; a teapot evolves into an ostrich; a marching phalanx of

ants carries grasshopper legs and a tiny human embryo. This fantastical

sequence seems to make a case for a transhumanist outlook, reinforced by

three polyurethane sculptures of anthropomorphic dogs, each titled

“Hundemensch.” Through April 14th. (Metro Pictures, 519 W. 24th St.

212-206-7100.)

DOWNTOWN

Elle Pérez

Photograph Courtesy Elle Pérez / 47 Canal

Nine enigmatic pictures by the New York photographer create a world of

their own. “Nicole” is an intimate, dusky portrait of a young woman

lying on a pink couch, her arms thrown above her head, glancing sideways

at the camera as her reflection is mirrored in a glossy coffee table

below. In “Stone Bloom,” an expanse of dark rock is marked with rust-red

splotches, echoing the blood-covered hand in “Dick,” a neighboring

cropped composition of tangled bare limbs. In previous work, Pérez has

focussed on L.G.B.T. night clubs and an underground wrestling scene in

the Bronx. This show, with its careful edit of subjects and moods, feels

unified by more formal associations, and the effect is as powerful as

ever. Through April 8th. (47 Canal, 291 Grand St. 646-415-7712.)

Jacolby Satterwhite

Pick up a pink glow-stick bracelet on your way into “Blessed Avenue,”

Satterwhite’s impressive début with the gallery. A large screen bisects

the black-walled space, playing a hallucinatory video—a Boschian sci-fi

tableau—which attests to the artist’s command of digital animation and

3-D-modelling software. In the endless simulated shot, dancers and S & M

performers populate a gay mega-club, a maze of fragmented machinery

apparently adrift in space. The dystopian scene has a surprisingly

poignant twist: the action is set to an electronic soundtrack created

from cassette tapes of the artist’s mother, singing a capella. In the

accompanying installation, a conceptual boutique, the artist hawks

affordable items from pill organizers to tambourines, all printed with

dashed-off drawings and charming, handwritten notes. Through May 6th.

(Brown, 291 Grand St. 212-627-5258.)

Sourse: newyorker.com