From the seventies until his death in August last year at the age of sixty six years, photographer Arlene Gottfried combed the streets of new York, parks, beaches, metro, and night clubs, in search of the shock of recognition you sometimes find in total strangers. She understood the certainty and security that will make the public face. She liked sharp cheekbones and strange, thin proportions; she loved the children, who behaved like adults, with Laden, the Sphinx-like features. When Gottfried died, she left behind fifteen thousand paintings. (For her first posthumous exhibition, “life of wandering” which is on view until the end of April, its owner, Daniel Cooney, has pores, through her archive, choosing fifty photographs that capture her fantastic openness.)

From left to right: Arlene Gottfried, Gilbert Gottfried, Gottfried and Karen.

Photo courtesy of the family of Gottfried

Gottfried came from a family of original. Her younger brother Gilbert Gottfried, comedian and actor, best known for voicing Iago, the loud parrot in Disney’s “Aladdin” and for what is widely recognized as the first 9/11 joke on the monks club roast in less than a month after the fall of the twin towers. The sonorous voice of Godfrey, to say nothing about his love for Blowjob jokes, contrary to his kindness and the depth of his family life. When the health of his sister began to deteriorate and she died from complications from breast cancer, he constantly visited her, keeping her spirit. “It’s a gift” she said “Gilbert,” a documentary on him that came out last year, “enable anxiety and doubt about the life on something funny.” Arlene shared that the gift towards her.

“Isabel Croft Jumping Rope,” Brooklyn, 1972.

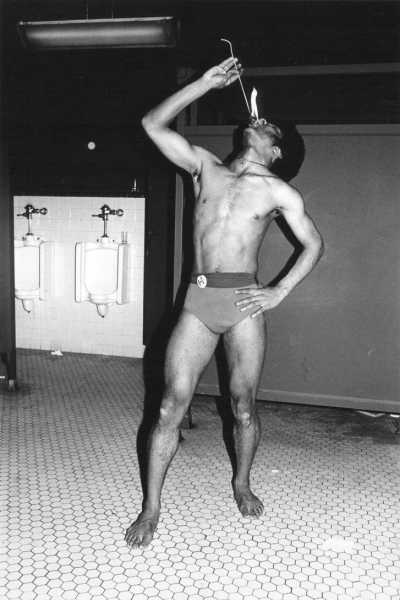

“The men’s room at the disco,” 1978.

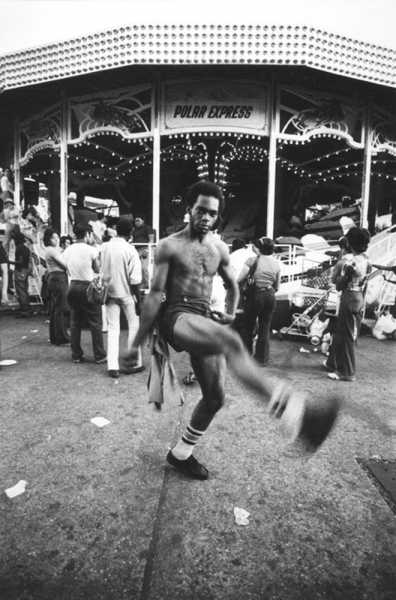

“Most people remember me as a very quiet growing up,” Gilbert told me recently. Arlene, by contrast, “were the most inclined to pick up a rock and see what crawled underneath.” In Gottfrieds were born in the Coney island five years, with his sister Karen between them—where their father ran to the store. Next to her amusements and seedy attractions, attracts new Yorkers from all walks of life. Arlene once compared this kind of therapy: seeing so many weirdos meant that for the rest of her life, she “never had difficulty with walking up to people and asking them to be photographed”. When the family moved to crown heights, she wandered too thrilled and from the community in the vicinity of Puerto Rico. To provoke her roaming, her father gave her an old camera. She carried it with her wherever she went.

“A woman with a baby,” nineteen-eighty.

“Woman with a bandage,” nineteen-eighty.

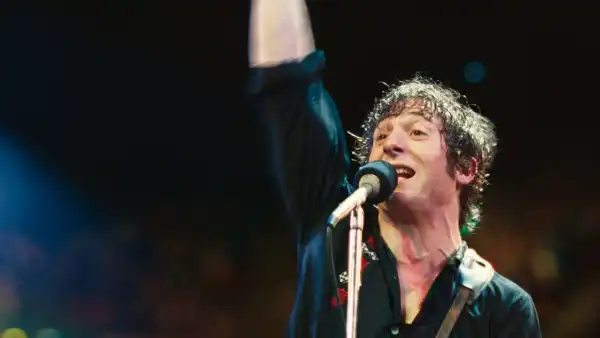

Gottfried studied photography at the fashion Institute of technology (she was the only woman in her class), and soon found commercial work. But in the world she was interested, said Gilbert, “people and scenes that the average person will see and go, ‘Oh, that looks bad—let’s cross the street. ” The work of Gottfried has been compared with Diane Arbus, who also had eyes for the freaks. But Gottfried was still attracted to the Frick-next: ensemble cast of the delicate of new York eccentrics, its cool customers and would-be fashionistas, vulnerable and indomitable. Many of the people shown in the “life of wandering” look as if they have become so accustomed to our screwing up their courage that they found peace in it; they just get out there and let it all hang out. The skater with the angelic face resting on the pavement. In the men’s restroom at the disco, a fire-eater dressed only in underpants, practices his craft near some urinals. A woman with a bandaged nose standing quietly against the chain link fence. Susan Sontag once despised street photographers to “cruising the urban Inferno”, but in the pictures of Gottfried that Ada feels more like a warm bath. There’s neighborliness in its approach, gentle curiosity. “It was a mixture of excitement, joy and warmth,” said she again, in 2016. “There was this striking beauty of the people.”

The “gospel” of nineteen nineties.

As Arlene has honed her craft, she helped Gilbert with his too. Noticing that he enjoyed joking and imitating the celebrities, she persuaded him to try an open MIC night, she heard in Manhattan. With Karen, the two of them “made the long journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan and found a place,” he told me. “They sat in the hall and I wrote my name down: ‘Gilbert, humorist.’ These were mainly folk singers and the like. I’m sure they thought it could be a disaster”.

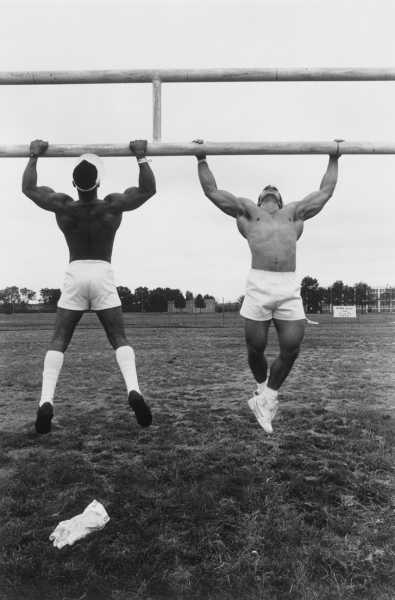

“The Olympics Rikers Island,” 1987.

“The Polar Express”, ” Coney Island” 1976.

Maybe it was, maybe it’s not years later, these two couldn’t even agree on where they went that night. It took so long, said Gilbert, was to encourage his sister. He cultivated a manic, madcap approach to the Desk that seemed to tickle her. One of his early bits were “Mickey mouse on acid”. (You can watch the clip on YouTube, Gilbert, flapping a pair of large red plate over his head, shrieking about the bad trip. He looks scared, but at the same time elated—as if his sister might want to take a picture.) Later, in the clubs, Gilbert would put Arlene’s guest list. When Caroline moved to times square, he told me: “it will be night for her. Her health was not so good then. She’s coming to get something to eat and watch the show.” Maybe she was the only one in the crowd who heard his real voice. In conversation, Gottfried is measured and calm, with no trace of his squeal trademark.

“First communion” in the early nineteen eighties.

“Purim, Williamsburg, Brooklyn,” the end of the seventies.

Although Gilbert has spent his career as a performer, and Arlene held her as observer, they shared a fixation on the masks that people wear to go on stage or to go through life. When, a few years ago, their mother fell ill, Arlene followed a desire to do away with these masks. In a photo essay called “mommy”, she has sealed the downfall of her mother, her stints in nursing homes and hospitals, in stark but compassionate detail. “I am afraid,” Arlene says in the documentary. “That’s how I knew how to cope with it, taking photos . . . that’s how I coped with the pain.” As a comic, Gilbert has built his career on raw nerve, touching all that had been told not to touch. (In 2011, after he joked on Twitter about the tsunami in Japan, Aflac dismissed it as honking the voice of their spokes-duck.) Arlene found on the same subject that was closed—the one who always came too early. “I wanted to help my mom to get off the bus because she was very weak,” Gilbert told me. “And my sister was taking pictures. I was horrified by the idea of photography, and confused. But I also knew it had to be done . . . She had to take these pictures”.

“Mom in the kitchen in Boro Park,” nineteen-nineties.

Not long after “Mama” was published, a private health Arlene began to falter. “I have stage four breast cancer,” she says in the film. “And I was so scared”. Her fear is simple in one scene when Gilbert accompanies her to the clinic, sitting beside her, as doctors put a tube in his chest. “If I were here only today, I’m in a horrible mood,” she says. “He makes me laugh”. Gilbert scrunches face and flops his tongue out of his mouth, and Arlene cracks.

“Mommy and grandma kiss,” nineteen-nineties.

Looking at her pictures, it seems to activate a sense of loss in Gilbert. “I see one, and I think, Oh, Gee, I was standing next to her when she was taken,” he said. Her work creates a family leave in the past, and with it, in the town, which was superseded by its own identity. (When I told Gilbert that I was living in my old neighborhood of crown heights, where I was among a demographic he once inveighed against wall Street Journal editorial titled “Brooklyn before the Hipsters,” he forgave me, with the caveat: “just . . . to go on drugs, at least”.) With photos, Arlene was, as she put it, “able to go to places other people will see only in pictures.” Back in the nineties, when she photographed the Eternal light community singers, a gospel choir from Harlem, she eventually joined the group. Gilbert told me: “I remember one of the guys from the choir at the funeral, spoke about how different she was, how unique. And he goes, how else do you explain how a Jewish girl from Brooklyn raised to be a Pentecostal gospel singer?’ ”

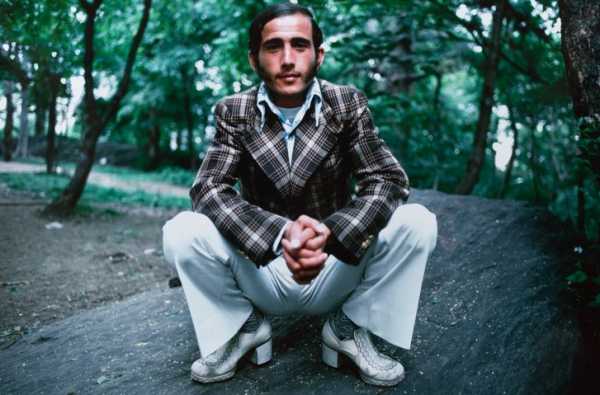

“People in Central Park” of the seventies.

Sourse: newyorker.com