Artist-portrait documentaries have become art-house staples, because they have a ready-made fan base, but also because many filmmakers, like many artists, have an inherent inclination to ponder artists’ lives and to lend their aesthetic enthusiasms an enduring form. Most of these films are as much about the filmmaker as about the subject—yet most of them have an arm’s-length, encyclopedia-like impersonality. There’s no danger of impersonality in “The Rest I Make Up,” Michelle Memran’s documentary portrait of the playwright María Irene Fornés (which screens August 23rd through the 29th, at MOMA). It’s very much a four-handed film, made (as the credits say) both by Memran and by Fornés, and it’s explicitly, inescapably about their collaboration. The resulting film is a profound, tragic, yet joyful vision of art. It’s more than the portrait of an artist (or even of two); it’s a revelation and exaltation of the artistic essence, of the very nature of an artist’s life as an unending act of creation in itself.

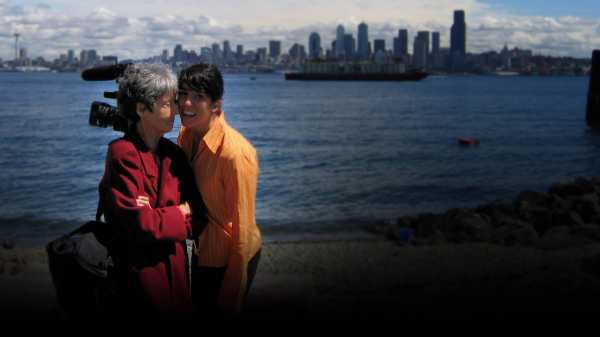

“The Rest I Make Up” distills fifteen years of connection between the filmmaker and the playwright into a brisk, teeming, aesthetically rarefied and emotionally raw eighty-minute jaunt into the void. Memran and Fornés met (as the film itself details) nearly two decades ago, when the filmmaker, then twenty-five, interviewed the playwright, who was in her sixties. They stayed in touch, and Memran began to film Fornés, at Brighton Beach, with no particular project in mind. The filming, along with the friendship, continued and deepened, and it was anchored, as the movie makes clear from the start, by a mystery of clear medical origin. Memran had wanted to write a play; she sought advice from Fornés, who had herself stopped writing but didn’t know why. Fornés was, from the first days of filming, suffering from memory loss, and, in the course of filming, she is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

In their decade-plus of filming, Memran became a frequent, seemingly near-constant companion to Fornés. The filming continues in a doctor’s office, where Fornés (accompanied by her sister, Carmen Nute), fills out a form to explain the reason for her visit, and struggles to write it—the phrase first emerges as “loss of me,” which is, surprisingly, quite the opposite of what the movie displays. On the contrary, even as Fornés’s short-term memory falters, her immediate observations and interpretations remain powerfully insightful, emotionally charged, and vitally imaginative.

Memran films in Fornés’s West Village apartment and the nearby streets; at public events, such as a celebration at the theatre La MaMa with its founder, Ellen Stewart; on a trip to Fornés’s native Cuba to visit members of her family whom she hasn’t seen in decades (she came to the United States at the age of fifteen, in 1945); on a visit to Nute in Miami on the way back from Cuba. She presents a useful compendium of Fornés’s career as a playwright, in which other luminaries of the theatre (including Edward Albee, Paula Vogel, and Oskar Eustis) detail the enduring and crucial influence that Fornés has had, as playwright and teacher. Her work is described as a reflection of her embrace of the unconscious, her teaching is hailed for her application of Method-acting liberations to the playwright’s practice, and the movie puts her artistic process—and its inseparability from her own automatic, immediate, yet deeply rooted powers of mind—on glorious yet poignant display.

Above all, the movie embodies Fornés’s inherently and irrepressibly creative presence. The text alone, transcribed, would be a primer in live-wire poetic lucidity. As they leave Fornés’s apartment and enter the elevator, Memran is having a little trouble with the camera. Fornés asks how long she has been a cinematographer; Memran says, “Not that long.” Fornés jokes, “A couple of hours,” and continues: “I do not trust professionals; but people who have confidence in their artistic”—she gives a confident click with a hearty fist-pump—“instinctive knowledge, are all on my side of the artistic road.”

The collaboration lurches through a wide range of modes and tones. Fornés is clear about her uninhibited self-revelation in the film—and Memran shows herself to be well aware of the ethics of filming Fornés in a state of increasing disability. Fornés speaks of her specific intention, even desire, to present herself fully and frankly to the camera, saying, “I prefer not to hide anything,” explaining, “If you expose anything about you . . . you are a freer person,” and adding that she trusts Memran. Fornés is also entirely aware of her performative presence: “The camera, to me, is my beloved . . . and I give everything I have to a camera.”

Even Fornés’s occasional loss of focus prompts insights of piercing authority, as when, in her apartment, seeing Memran filming her, she asks, “Who is doing the writing?” Memran says, “You are,” and Fornés says to the camera, “I’m using now Michelle’s language; she calls talking to a camera writing.” Albee characterizes Fornés’s theatrical art as “taking stuff from the unconscious and letting that create form . . . she discovers what she’s writing by writing it.”

Fornés’s idea of writing is existential, physical, inseparable (she says) from performance—and she delivers an extraordinary performance throughout “The Rest I Make Up,” dancing, imitating the street-strutting styles of her Cuban youth, teasing Memran and the camera with incisive flashes of seductive delight. One of Fornés’s former partners, Harriet Sohmers Zwerling, speaks of the extraordinary erotic power that Fornés exerted on her, decades ago, saying that she called Fornés “Doña Juana.” Fornés speaks of her relationship with Susan Sontag, calling her “the love of my life”—yet even this discussion is prompted by a magnificent turn of spontaneous artistry.

The story comes up while they’re sitting at a café table in Cuba. Fornés can’t remember how she and Memran met; Memran asks her to make up a story about it. Fornés tells one, about an encounter in a Paris café, loses her way midstory, and then says, “It was not Michelle that I met in a café in Paris, it was Susan Sontag.” Memran asks about Sontag; in her response, Fornés says, “Right now, my eyes are beginning to tear, and this is one hundred and fifty-five years later. . . . Why is someone the love of your life? It is a mystery, it is magic. It is as real as this table, but you cannot analyze it; because it is.”

In her recollections and insistences, there’s a powerful, if fragmentary, view of social history at work. Fornés recalls having been beautiful in her youth—and of having deliberately made herself look ugly in order to avoid the catcalls of men in Cuba, even when she was nine or ten. (She also asks Memran if such a thing as catcalling still happens and is dismayed to learn from Memran that it does.) Fornés is entirely lucid about the dangers faced by L.G.B.T.Q. people in Cuba, where it’s impossible to live openly, and she intentionally remains vague about her personal life when speaking with her relatives there. Yet, the day after she and Memran returned from their two-week trip to Cuba, Fornés has no recollection of having been there.

While there, Fornés tells Memran, “The artist is a person who is made of two: one who goes in and another who goes out. The one who goes in enters through observation and, in some mysterious way, then transforms it to produce a thought, a poem.” Soon thereafter, Fornés, visiting her sister Nute, in Miami, is encouraged to stay there because of her increasing difficulty living alone. She resists moving, because she needs to be in New York’s theatrical community in order to write plays (she offers, throughout, a moving tribute to the city), and is surprised to learn from Memran that she hasn’t, at the time, written a play in years. Yet Fornés has, nonetheless, written a movie, given a performance, spoken poetry, created—in collaboration with Memran—theatrical moments of exquisite cinematic power.

Sourse: newyorker.com