Lois Weber’s films have been long unknown, mostly lost; some of the few surviving ones only recently became available and are getting the attention that they deserve. But, a century ago, between 1908 and 1921, she was making hundreds of short films and dozens of features and was the most prominent and most successful female filmmaker of the time. She was also one of the most original directors of the silent-film era—she was an artist of historic power, and she knew it. Her accounts of her art—and of her career—is found in a remarkable new book, “Lois Weber: Interviews,” edited by Martin F. Norden, which features a diverse and peculiar batch of texts ranging from 1912 to 1933. Her remarks, mainly taken from brief articles in which she’s quoted a few lines at a time, reveal an extraordinarily self-conscious sense of her artistry and of the nature of movies, and they speak as clearly to the present day as to her own time.

It helps to know that Weber, a onetime Christian missionary, made films with an explicitly moralizing, educational purpose, she herself called them “propaganda.” The films addressed social issues, and, in particular, ordeals endured by women in modern society (and even, sometimes, in historical societies), involving poverty (and men who prey on poor women), birth control, gossip, religious hypocrisy, and the over-all prevalence of cavalier depravity (sometimes on the part of women, too). At the same time, Weber was a fanatical realist whose movies are rich in physical and behavioral detail—and she was also a fantasist whose extravagant visions ranged from the psychological to the metaphysical. She was, furthermore, a master technician—her first films, from 1908, were short talking pictures, in which the images were synchronized to records that played along with them—and her artistic inventiveness went hand in hand with her advances in movie technology. (Norden’s book offers crucial biographical elements—a detailed chronology of her life and also a filmography.)

As early as 1912, enthusing about the rapid pace of artistic and technical progress, she anticipated that movies would very soon be included among the high arts and would even be dominant among them. “The film millennium is not far off,” she predicted. That same year, when asked about the use of intertitles, she asserted that they’re part of a director’s work and that “the management that interferes with the good director is in the wrong business.” Her idea of movies was imaginative and wide-ranging; she said that an emphasis on suspenseful stories got in the way of art and progress and believed that movie genres should include “poetry, more good prose, some philosophy, history, geography, religion, and even a few character sketches.” She was devoted to cinema’s educational potential; she expected that movies would soon be shown in classrooms and houses of worship. She also foresaw the important role that movies would have in the field of science and specifically mentioned the significance of slow-motion cameras for analytical purposes. (She was also politically active; she ran for office, in 1913, on a suffrage-party ticket.)

Weber declared that she wanted to function as her movie studio’s “editorial page” and added, “I admit frankly that I get a large share of my plots from the newspapers” and also “the little, delicate glimpses of human motives and human lives which I catch between the lines.” Weber had little faith in screenplays brought to her by other writers; she thought little of a screenwriter’s independent contribution apart from the direction, saying, “The idea is the thing, if it be only a few words scribbled on an envelope or cuff.” In any case, she either wrote her own scripts or rewrote other people’s scripts to suit her own purposes. She believed that a good movie results from a director’s “inspiration; a definite though perhaps fleeting vision,” which, for her, meant envisioning a film in advance, “in its entirety.” In 1921, a reporter described Weber as what we’d now consider an auteur. “She writes her own stories and continuity, selects her casts, directs the picture, plans to the minutest detail all the scenic effects, and, finally, titles, cuts, and assembles the film,” the reporter wrote of Weber, adding, “Few men have assumed such a responsibility.”

MORE FROM

The Front Row

The Faux-Progressive Politics of “Captain Marvel”

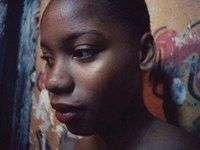

“Black Mother,” Reviewed: Khalik Allah’s Deeply Personal Portrait of Jamaican Life

“An Elephant Sitting Still,” Reviewed: A Young Chinese Filmmaker’s Masterly Portrait of Political and Intimate Despair

The Most Disturbing Aspect of “Greta”

What to Stream This Weekend: “Poor White Trash”

Bruno Dumont’s Vision of a Confused, Far-Right, Alienated France

Weber declared, “A real director should be absolute”; she repudiated the very concept that a producer could interfere with her work. Her autonomy, for the core part of her career, was also financial and administrative, and that autonomy was channelled into her artistic practice. She kept her crew together, from film to film, in a “unit” of her own. When she built sets, she didn’t build only “corners of sets.” She said, “I never know when I may wish to use the whole set, and I like to feel that I can branch out where I wish.” Her total vision also entailed total freedom to invent, to improvise during the shoot. In 1917, Weber founded her own studio, and she planned to fulfill an artistic dream there, “to have every set needed in a picture ready before I begin to take a scene. In that way I shall be able to take my whole picture practically in sequence.” Weber also felt that this continuity would enable actors to better build their characters from scene to scene.

Nonetheless, when Weber had her own studio, she hardly filmed in it: she found that she preferred to shoot on location, renting inhabited houses for the specificity of the owners’ décor, directing scenes, as one reporter said, in a jail and a church, filming another scene, as Weber said, “in the hubbub of the shopping district.” Her obsession with sharply defined moral points was matched by an obsession with physical and psychological realism; she favored typecasting and, that way, often propelled bit players into leading roles. (She was considered a major star-maker, though the stars she made, such as Billie Dove and Claire Windsor, were forgotten when talkies came in.) Weber’s acute sense of morality was also complex; she repudiated simplistic sentimentality and wouldn’t allow a hero to be “a dummy concocted of all the impossible virtues a scenario writer could imagine.” A movie was supposed to “have some intimate bearing on the lives of the people who will see them.” She thought that technology would help—she wanted to make color films and, even more ardently, hoped to be able to work with “stereoscopy,” a.k.a. 3-D films.

Weber crafted and deployed sophisticated special effects in her movies. When directing the historical drama “The Dumb Girl of Portici,” the only movie in which the dancer Anna Pavlova stars, Weber invented a complex system of “animated titles” involving exactingly calibrated mirrors. For another film, she devised systems of three images deployed across the screen. For her 1921 film “What Do Men Want?,” she used a different effect, which a journalist described:

There was a scene, for instance, where a pool-room hanger-on ogled a

girl on the street corner, and mentally disrobed her. The outlines of

her body were made to show through her clothes—in a double exposure,

of course—and the power-that-be fairly stuttered in an effort to

express their horror.

“But men do it,” Miss Weber told me. “I have seen them do it numberless times! It struck home, that’s all.”

Weber had trouble with censorship. In New York City, a drama about the prosecution of a birth-control advocate, based on the story of Margaret Sanger, was banned; Weber successfully sued to have the decision overturned. She also had trouble with fretful exhibitors and, ultimately, with producers. Hollywood became increasingly standardized and corporatized in the late nineteen-tens and early nineteen-twenties. Weber herself suffered personal problems—a badly broken arm and what one journalist called “a nervous breakdown.” She and her husband and business partner, Phillips Smalley, divorced. She withdrew from the industry for a few years and, upon returning, lost her autonomy. Her “unit” was disbanded, she explains in one article, and she had to cope with a different crew from film to film—which, as a female director, she found to be a problem. The new crew, she said, was “an alien group of men who had never worked under me and who suffered resentment and hurt pride at being placed under a woman’s direction.”

In 1928, she wrote of the rapidly declining fortunes of female directors in Hollywood (of whom she was only one of many), saying, “Women entering the field now find it practically closed. Frequently a male writer is given a directorial chance on the supposition that he ought to know better than anyone else how his story should be presented on the screen. But you do not hear of a woman writer being so favored.” Moreover, she wrote, “Men bosses are also less tolerant of failure or mediocrity in a woman director than in a man.” The sexist culture on sets and in offices also posed a problem. “Men also like men’s talk in a business which may or may not always be attuned to the ears of women,” she wrote. At the age of forty-nine, Weber was washed up in the movie business.

Still, Weber wasn’t the only great director of the silent era who had trouble with producers and whose careers were truncated—D. W. Griffith and Erich von Stroheim were also pushed aside around the same time. In her heyday—in 1916, when she was earning five thousand dollars a week ($121,958 in 2019)—Weber anticipated the problem. She feared pandering to the public no less than she feared censorship. “ ‘The people’ have always been reactionary in their ideas. . . . If ‘the people’ alone were consulted, we should still be in the patriarchal stage,” she wrote. She believed that art—her art—was a crucial source of public education and of progress, albeit one with a problem, because, she said, “the true artist is and always has been ahead of his time.” She was confident, though, in the artist’s ability to prevail in the long run. “If his art-message is true, the world grows to him,” she wrote. “I hope and pray for the recognition of motion pictures as an art.”

As it turns out, it took about a hundred years for the world to come around again to Weber’s “art-message.” In the meantime, she—and “the people”—endured the corporatization of Hollywood, the inhibition and truncation of many great directors’ careers, and the mass popularization of movies under the iron fist of studio bosses and producers. Long after Weber’s death, directors, including many who worked in the Hollywood-studio system, were widely recognized as artists. Yet the results of their acclaim, over the past half century and more, has been paradoxical: often, a critical celebration of directors’ art morphs into a celebration of Hollywood norms themselves. Rather than praising the exception, many critics have come to praise the rule, and from recognition of individual “genius” (a word applied to Weber by many writers in this volume) has come, rather, dedication to the so-called genius of the system. That’s why, though Weber is now, a century later, receiving her long-overdue recognition, other filmmakers, in the present day—including many of the best female filmmakers—struggle, in turn, to be recognized.

Sourse: newyorker.com