Of all the images that the photographer Clémentine Schneidermann and the art director Charlotte James have made of (and with) children in South Wales, few show interior scenes. Here is one, in which, amid the gloom and clatter of a community center, two figures are brightly lit. A young girl with blond ringlets gives the camera a bored glare, while a red-haired boy, wearing a luxe hillock of green fake fur, flashes us his newly augmented fingernails. Beside his sullen companion, the boy looks like a prepubescent night-club impresario, or a glamorous tween art star. In a photographic project that invites children to style and invent themselves, he might be the most daring of all. Elsewhere, you’ll spot him in platform boots and off-the-shoulder brown velour, his face full of cheek, and his cigarette delicately plied.

The series is titled “It’s Called Ffasiwn”—the word means “fashion” in Welsh—and twenty of the photographs will go on view at the Martin Parr Foundation, in Bristol, on March 27th. (Since the nineteen-seventies, Parr, the celebrated English photographer, has been documenting various garish strata of British life. His foundation’s gallery opened in 2017.) Schneidermann is from Paris, and moved to Wales as a student; James is a native of Merthyr Tydfil, the town in and around which most of the photographs were taken. The two met in 2015, and soon began running workshops for eight-to-twelve-year-olds—James teaching the rudiments of design, tailoring, and styling—before photographing them in the mostly deprived districts where the children live. The first shoot, in November, 2015, produced one of the most startling pictures. Five girls, photographed in front of a stone wall and scraggy hillside, have tricked themselves out in full Gothic-Victorian funeral garb: black lace mantillas, black fans, and teary marcelled locks.

“Cherry,” Gellideg, 2017.

“It’s Called Fashion (Look it Up), Merthyr Tydfil,” 2016.

“Rio, Labour Club,” 2017.

Many of the photographs seem to document some vernacular ritual; one shows what I thought, at first glance, was a group of Catholic girls dressed for First Holy Communion, or for regional variations of folk dance. But the girls, bride-like in white, have climbed onto the roof of a low concrete building, and, in another image, six kids, clad in more green fur, have convened on a housing estate in an eerie, children-of-the-damned array. If this is fashion, then the trend among these girls and (far fewer) boys is for an uncanny amalgam of childish dress-up—a girl in a laundry-bag dress, a little boy trimmed with gold tinsel—and gleeful-sinister surrealism. The workshops and the photographic series are carrying on as the models grow older: Will they lose their edge as the strictures of embarrassed adolescence set in?

“Trago Mills, Merthyr,” 2018.

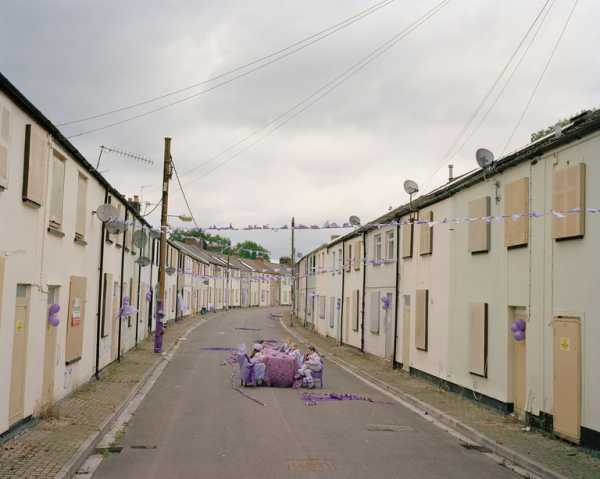

“Summer Street Party, Merthyr Vale,” 2018.

The Welsh valleys—their beauty, their culture, their economic depredations—have long been subjects of photographic attention, both documentary and visionary. In 1950, W. Eugene Smith was dispatched to Wales by Life to record the general-election campaign of the Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee, and came back with darkling studies of generations of miners. Robert Frank followed, three years later, photographing more coal-darkened faces against slag heaps and terraced cottages hugging the hillsides. Bruce Davidson, in the mid-nineteen-sixties, added color to this image repertoire, but his famous picture of a Welsh bride and groom, taken on a hill above a power station’s cooling towers, is in black and white, cleaving to a certain monochrome vision of poverty and profundity.

“Spring, Gurnos,” 2017.

“Valentine Disco Party, Gurnos Social Club,” 2018.

“Tia with a Ginger Cat, Winchestown,” 2018.

This mid-century photographic bequest surely haunts some of the work that Schneidermann, James, and their young collaborators have made. But their photographs respond more directly to a later iconography. Most Welsh coal mines were closed by the end of the nineteen-eighties; they were already depleted, and their ends hastened by Thatcherite decree. Images of the valleys now signal post-industrial decline and, lately, a degree of Brexit-voting political self-harm. “It’s Called Ffasiwn” depicts spalling gray housing estates, but they are not always what they seem. In a photograph that will be blown up to wallpaper scale in the Bristol exhibition, a group of children parade in lilac costumes along an abandoned street. The shuttered windows and doors have nothing to do with poverty, only with threatened flooding from a nearby river. The kids carry on as if it’s a royal jubilee—as so often, glamour, comedy, and some innocent purchase on the future have met in the ruins.

“Gellideg,” 2017.

“Last Days of Summer, Blaenavon,” 2018.

Sourse: newyorker.com