The Quad Cinema, in Manhattan, ran a miniature film festival celebrating the limited celluloid legacy of Bob Fosse, a genius who was as lauded as a choreographer as he was underrated as a film director. Because Fosse only got to direct five movies and one screening-worthy television special before he died, in 1987, the Quad, to fill out the menu, included in its program four films that he appeared in and choreographed. I am not working now—my TV show “Difficult People” was cancelled almost a year ago—and New York has been experiencing a heat wave so brutal that it evoked the notion of Hell having only been a metaphor for climate change, so I decided to see all of the eight movies and the television special (1972’s “Liza with a ‘Z’ ”) that were shown as part of the Quad’s “Performance Anxieties: Fosse at the Movies.” Here is my log of events.

Saturday, August 4th

Mariel Hemingway in “Star 80,” 1983.

Photograph from Warner Bros / Everett. Courtesy Quad Cinema

I see “Star 80” for the first time—sadly, it’s the last film Fosse made. He should have gone out on “All That Jazz,” right?

“Star 80” is based on the murder of the Playboy Playmate Dorothy Stratten by her scumbag estranged husband. It’s stylish, sexy, and brutal—I made the mistake of watching Brian De Palma’s “Body Double” earlier in the day, so I go to bed with quite enough upsetting images of violence against sexy ladies, thank you very much. “Star 80” is like an “SCTV” parody of a Fosse film, or, as Pauline Kael put it back in the day, Fosse “uses his whole pack of tricks”: there are lots of talking-head interviews about Stratten’s murder, nonlinear chronology, jump cuts, extreme closeups, scenes in strip clubs, and men with black chest hair being edgy. Mariel Hemingway aw-shucks-es her way through the role of Dorothy Stratten, and she’s so innocent that even her bare nipples seem like cheek dimples. I wonder whether Fosse was able to relate to the obsession of Eric Roberts’s stalker character; Fosse seemed like a guy who only stalked the project he was working on. This is a nasty little movie that was highly affecting.

Sunday, August 5th

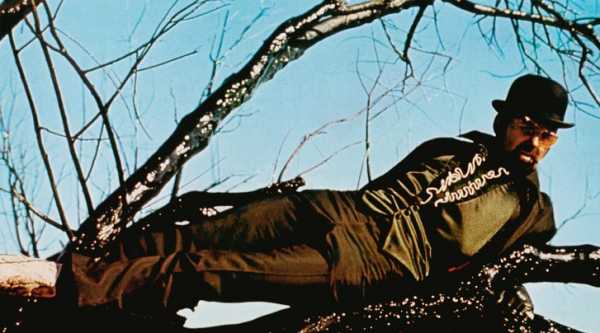

Bob Fosse in “The Little Prince,” 1974.

Photograph from Everett. Courtesy Quad Cinema

“The Little Prince,” from 1974, plays at 1 P.M. It is no bueno. In between cutaways to non-fables and musical scrapple from Lerner and Loewe, a little British boy, whose hair was probably set in curlers and dried under one of those inflatable bonnets, spends most of the movie in the desert talking to a grown man who forgot how to be a little kid at some point in his life. Gene Wilder is the highlight of the movie; he plays a fox. He and Barbra Streisand are the C.E.O.s of soulful Jewish blue eyes. There’s really only one woman in the movie, and that’s Donna McKechnie, playing a blowsy rose. She doesn’t even really get to sing or dance: what a ripoff.

Bob Fosse plays a snake in a routine that’s charted directly to Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean.” He’s a little too tan, his BluBlockers are a little too tinted, and his hair and beard are so fakely dark that they are Grecian Formulaic. He’s also wearing way too many heavy black layers, considering the sun exposure, and, frankly, he’s a bit of a bummer in a bowler hat. Fosse is not the best delivery method for his own genius, meaning he’s not as good a dancer as he is a director or choreographer. Look, I’m a writer-performer who lives in constant fear that I have no right to be in front of the camera, so this is all very hard-to-throw-stones-ish of me, but it wasn’t until I got to the second movie of the afternoon, “Damn Yankees,” and I was watching Gwen Verdon, that I realized: Bob Fosse was a great painter who couldn’t make a masterpiece until he met his paintbrush, and that paintbrush was Gwen Verdon.

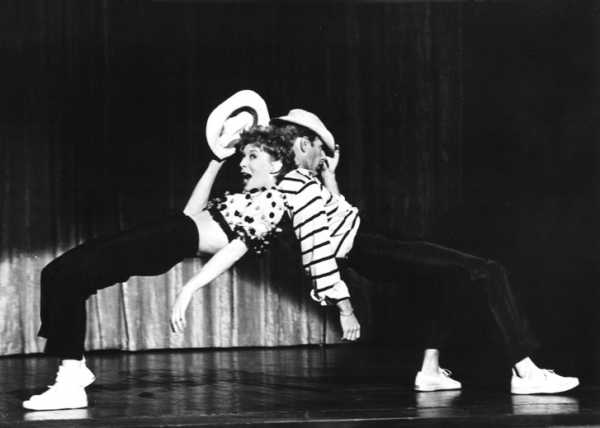

Gwen Verdon and Bob Fosse in “Damn Yankees,” 1958.

Photograph from Everett. Courtesy Quad Cinema

“Damn Yankees” is lemonade on a hot day; it’s loopy and short and funny and fast, plus, the songs are great. Verdon, its star and Fosse’s longtime spouse and collaborator, is precise, daffy, funny, and sexy. She’s such a great actor, she convinces you that she’s not only as beautiful as her character, Lola, has to be, but that she’s as gorgeous as the movie star a studio would have otherwise cast in her role if it had not been for the fluke of stars aligning, or whatever has to happen metaphysically, for a Broadway actress who originated a role to get the privilege to do what she did onstage, onscreen.

Gwen Verdon’s dancing is archery: she is a bull’s-eye-bound soaring arrow shooting straight from Fosse’s bow. As lush and as juicily sublime as Ann Reinking was dancing for Fosse later, Gwen Verdon was the “A” in the alphabet, the gold standard, an apple, a red ribbon with freckled shoulders. Her singing and dancing “Whatever Lola Wants” to Tab Hunter in the locker room is canon. You must watch it on YouTube this instant. Fosse has an exhaustive record of both objectifying women and, also, letting female performers make fun of their sex appeal by being so hyperbolically feminine that it’s funny. Lola as seductress is a joke that I didn’t get when I was a little girl; I took it for granted that, in order to seduce a man, you affect a coochie-coochie quasi-Latinx accent and strip down to a merry widow from a mariachi-themed American Girl doll ensemble. I now see that everything Gwen’s Lola does to “seduce” is drag; it’s a parody of femaleness.

From left: Betty Garrett, Kurt Kasznar, and Janet Leigh in “My Sister Eileen,” 1955.

Photograph from Everett. Courtesy Quad Cinema

I stayed for a third movie, “My Sister Eileen.” It’s a trifle that I have already forgotten, but it was better than “The Little Prince.” It stars Janet Leigh as Eileen and Betty Garrett as her homely-but-J.K.-actually-totally-beautiful sister. Bob Fosse and Jack Lemmon play the girls’ respective love interests, but, honestly, it doesn’t matter. According to IMDb, the tagline for “My Sister Eileen” is “That Joyous New Musical!,” which is fine. The actors in the film all danced as if Fosse’s choreography weren’t the stuff of legend; they’re not phoning it in, but they’re not being rigid and reverent enough, either.

Monday, August 6th

Liza Minnelli in “Cabaret,” 1972.

Courtesy Quad Cinema

It’s time for “Cabaret.” Nicole Fosse, the daughter of Gwen Vernon and Bob Fosse, and who played Kristine in the terrible 1985 movie adaptation of “A Chorus Line,” is there in person to tell us that she and her mom left the set in Germany to travel to the U.S. so they could personally pick up a cuter gorilla costume, per the studio’s wishes. The gorilla costume Bob Fosse had originally wanted to use for “If You Could See Her,” a number so disturbing they had to cut it from the first production of the Broadway show, was apparently too ugly and upsetting. She asked if anyone had questions, and I asked how old Nicole was when she saw this movie for the first time. She said she was seven when they filmed it, nine when she saw it. I asked if it had scared her as a child. It hadn’t. Tough as shit, Nicole Fuckin’ Fosse.

Then I watched “Cabaret” on the big screen for the first time. In the theatre, it is more than sinister glamour marbled into the rib-eye flesh of a cult musical: it is sweeping high art—a knockout masterpiece—with the scale and bearing of those big-man seventies movies, the ones made by Italians and slobbered over by Ms. Kael.

Now I will state the obvious: this movie is a knockout masterpiece. Liza Minnelli is a great actress for many reasons, but one of them is that she is able to feel things more strongly than other people can. Another is that she seems to have very few stops between her brain and her face. Her big, hypnotizing face, sanctified in its symmetry and proportions, is a mirror—or live-streaming security-cam footage—of the exact thing she’s thinking and feeling every moment. I still wonder what the hell Michael York’s problem is at the end, when he goes all distant at the picnic. Yes, Sally makes the decision not to be his wife and move away and raise a family, but in a way, I saw her reacting to him from a place of intuition—he was beginning to disengage, and she didn’t want to be rejected. But, then again, how great is Sally’s intuition if she decides to stay in Weimar Berlin while the shit hits the swastika-shaped blades in the fan?

There remains nothing better than Sally’s face going from regretful and introspective to showbiz-toothpaste sunshine, beaming in a restraint-laden waist-up shot right before she sings “Cabaret” to a room full of, it turns out, more Nazis than is ideal. It shocked me that the second shot in that film is of one of the Kit Kat’s audience members in formation of an Otto Dix painting. What balls Fosse had.

Of course I thought about America in 2018 watching it. Of course I shuddered at the insidiousness of a burgeoning movement. It’s the dread that’s present in the flashbacks on “A Handmaid’s Tale,” too—a country on the precipice of Kristallnacht. You watch things begin to happen. Your moron neighbor babbles over the morning paper about how he thinks there is a Jewish conspiracy, and the next thing you know, Nazis have killed Marisa Berenson’s dog. I hope we aren’t all Sally Bowles onstage, pleading, with her divinely decadent dark green nails, for you to put down the knitting while the world burns. Still, I resolve to be more like Sally Bowles in that, when I receive a compliment going forward, I will reply, “I know, darling!” In a film about encroaching death, Liza’s performance is pure life.

Tuesday, August 7th

Liza Minnelli in “Liza with a ‘Z’,” 1972.

Photograph from Everett. Courtesy Quad Cinema

In “Liza with a ‘Z,’ ” Liza Minnelli is a ludicrous noodle. She shimmies around the stage with ants in her pants; her breasts bounce and her slim hips, when checked, dash for the wings like pebbles out of a slingshot, but even though her star-billing body is a wild, cursive love letter, you can’t forget to study her face the whole time. Because while “Liza with a ‘Z’ ” features outstanding singing and dancing, it primarily shows off Liza Minnelli’s ability to act. She becomes a different character from song to song, and commits to that character’s thinking, feeling, and sensitive intention with every one of her lovely hand gestures or eyebrow furrows or pouts or guffaws. I realize, during the finale—a medley of songs from “Cabaret”—that Liza performed this dual débutante ball/victory-lap concert only three years after her mother died. This gives me chills, and I wonder whether Judy had to leave the world in order for Liza to fully come into her own. I get emotional.

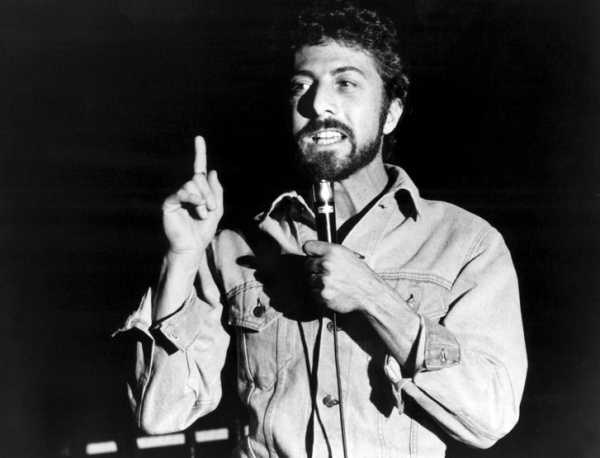

Dustin Hoffman in “Lenny,” 1974.

Photograph from Everett. Courtesy Quad Cinema

After “Liza with a ‘Z,’ ” I stayed for “Lenny,” which I’d never seen before. It was a lot less sprawling than I expected based on its sweeping themes of censorship and heroism and a hero’s journey in the form of an iconoclast raging against a specific machine. Lenny Bruce’s real-life œuvre has never really fascinated or entertained me, to be honest: plus, his fans rival Bill Hicks’s in the insufferability department. The ratio of social importance to actual LOLs when it came to socially strident bros like Bruce was always paltry to me, and, finally, I just have a very low tolerance for white people comparing things that aren’t jazz to jazz and saying “man” after sentences that would have been perfectly fine ending with a dignified period.

But what’s so great about “Lenny” is that Fosse’s directorial and editing styles blend harmoniously with Lenny Bruce’s style. Fosse’s aesthetic titrates Bruce’s self-righteousness while keeping him in the picture as an important artist. Dustin Hoffman is phenomenal and uncanny: I believed he was Lenny Bruce. The strip-club footage is cut like “Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!” and Valerie Perrine is lovely. I begin to get mad at men. I think about the Fosse book by Sam Wasson that Lin-Manuel Miranda is adapting for FX. The book is good, but I don’t think Wasson sufficiently pathologizes Fosse’s sex addiction. I read that Fosse and Dustin Hoffman didn’t get along; that’s no shocker. They were two jerks with their seventies schlongs swinging all over the place and getting away with murder because of their talent. A tale as old as time, but hurting Gwen Verdon’s feelings should have been a felony.

Wednesday, August 8th

Shirley MacLaine and John McMartin in “Sweet Charity,” 1969.

Photograph by Mary Evans / Universal Pictures / Everett. Courtesy Quad Cinema

“Sweet Charity” seems to be the first and last movie that Fosse ever thought he would do, because it has, to paraphrase Stefon, everything. There are so many visual effects and tricks. There are extended sequences where the camera moves over still shots of the action like the opening credits of “Family Ties.” Shirley MacLaine, doing her best Gwen Verdon impression, gambols onscreen like a giddy doo-dah, and then she does the same thing in reverse. Film is sped up and slowed down and overexposed for novelty. Somebody painted an eye on Sammy Davis, Jr.,’s hand. It’s fabulous, but, twenty minutes in, after the busy, madcap, Biblically essential “Rich Man’s Frug” and a lot of freeze frames, I (Carrie Bradshaw voice) couldn’t help but wonder: Who was this movie for? It reminded me of the Monkees’ movie “Head”: both were psychedelic flops. The problem with “Head” is that, because it was rated R, kids who liked the Monkees couldn’t go see it, and the hipsters who took LSD, for whom the movie’s trippy content was ideally suited, wouldn’t go and spend their cash on a film starring the fucking Monkees. “Sweet Charity” seems too weird for lovers of musicals, and too square for pot smokers. I absolutely love it.

I ponder Fosse’s place on the countercultural spectrum. “Sweet Charity” came out, and bombed, in 1969, a time when you had to pick a side in the culture wars: hip versus square.. Fosse has a place in both worlds. The seventies, when he was, in my opinion, at his peak artistically, were a cynical, nasty tunnel of terror when Americans had abandoned the glittering hope of post–Second World War boomerism and flower children had survived the aftershocks of the sexual revolution to realize that things were more complicated when you weren’t high all the time. “Cabaret” was on point. Then Watergate happened, and nobody agreed on what was right and what was wrong. Then everything got dark, and the sequins on the black velvet seemed like a tacky joke.

Thursday, August 9th

I end the week with a screening of “All That Jazz,” my favorite Fosse movie. I see this movie alone, because that’s how it worked out, but also because we all die alone. It remains shimmering and glib and grandiose, and it still leaves me gutted. I sob at the end, when Roy Scheider hugs his daughter during “Bye Bye Love,” and think about other male auteurs whose attitudes toward women are, to be generous, complicated, but who deify their daughters in their art.

I didn’t used to love Fosse. When I was in college, the 1996 revival of “Chicago” was playing on Broadway, and I was turned off by its ad campaign. All those girls in black and white on the sides of buses with glossy lips posing in fishnet body stockings and pleather caps smacked too much of effort to be sexy or cool. In retrospect, I don’t think I was able to see the difference between the old-timey show-biz acts Fosse was inspired by and the language he created, with matching penmanship, from his experiences in the gutter. It wasn’t until I took a deep dive into the aesthetics of the early seventies that I realized how irreverent he was: the 1972 musical “Pippin” was ugly-beautiful. All those grinning m.c.s and players were stand-ins for the devil. Any chorus girls posing in a line had communicable diseases and terrible secrets. And then, his films. I wish there had been more.

Yeah, Fosse was cool. Not just jazz or Broadway cool, either. How many people create their own visual language? Who else used the medium of human beings to create a new way of seeing the entire world? I go back home feeling like I’m a lazy slug. Fosse worked so hard. He would casually reference dying at sixty as his goal, and that’s how he ended his life: at sixty, en route to the opening of the Washington, D.C., revival of “Sweet Charity” starring Donna McKechnie. He collapsed in the street, and died of a heart attack. Gwen Verdon, his long-suffering, oft-humiliated partner, collaborator, and wife, was with him. Maybe you don’t have to die alone after all.

Sourse: newyorker.com