In 1997, after watching a friend, inspired by “Jerry Maguire,” cold-call a big sports agency for an internship, I talked my way into a summer job at an Asian-American newspaper in San Francisco’s Chinatown. It was my first brush with professional journalism, and everything about it was intoxicating. The newsroom was filled with Asian-Americans unlike any I had ever met—people who looked like my parents but spoke in the cadences of the jaded gumshoe. I studied the way they transcribed their interviews in shorthand, the way they checked in with their sources and shit-talked the editor, their ability to discern when a local restaurant microwaved their food. The boss thought my name was Curtis, for some reason. I had a small desk in a room in the back, and when I wasn’t running errands I could write arts pieces.

I was assigned to cover an Asian-American film festival somewhere in Southern California. That year there were four films, by filmmakers in their twenties and thirties, that everyone was excited about, in part because they were all so different from each other. “Yellow,” Chris Chan Lee’s stylish coming-of-age story, was full of high-school kids flirting with one another, hanging out in parking lots, and scheming. Quentin Lee and Justin Lin’s trippy “Shopping for Fangs” felt like Wong Kar-wai adapting Franz Kafka. Rea Tajiri’s “Strawberry Fields” was a haunting road trip across middle America and deep into the past, in which a fierce young Japanese-American woman pieces together her family’s long-forgotten experience in an internment camp during the Second World War. And “Sunsets,” directed by the cousins Eric Nakamura and Michael Idemoto, was a black-and-white film about slacker buddies who seem both bereft of ambition and deeply appreciative of every new day.

The directors of these movies were known, collectively, as the “Class of ’97,” and they seemed like the start of something. In 1993, Wayne Wang had adapted Amy Tan’s best-seller “The Joy Luck Club,” and a year later ABC had briefly aired a sitcom called “All-American Girl,” based on the standup comedy of Margaret Cho—both of which came to be seen in retrospect as thwarted opportunities for Asian-American storytelling to break into the mainstream. But as a sarcastic, stubborn teen-ager I felt ambivalent about Wang’s movie, and didn’t see it until years later. (A white teacher had recommended Tan’s novel to me, saying that it had taught her a lot about my people. This did not have the intended effect.) I didn’t learn about “All-American Girl” until it had already been cancelled. Though I’d rarely glimpsed people like my family in the novels I read at school, or in the American movies and television I would have rather been watching at home, I didn’t feel starved for mainstream representation. There was an eclectic world of Asian people around me: at the local market, at our boisterous family get-togethers every weekend, and in all the slapstick comedies, historical epics, and gangster videos imported from Taiwan and Hong Kong that I grew to adore. Maybe I didn’t know that it was something I was allowed to desire.

But I was excited about the Class of ’97. Their movies didn’t seem particularly hung up on what it meant to be Asian-American, at least not in any explicit terms; they were alternately mystical and mundane, anguished and breezy. I used my assignment as an excuse to talk to Nakamura, whom I already admired from afar, on account of Giant Robot, a zine that he and his friend Martin Wong published. I asked him why he’d decided to make “Sunsets.” He said that sometimes you just have to try something really big, and no matter how it turns out it will change you. I remember looking at the tape recorder, to make sure that I could listen to this sage advice again someday. And I remember looking up at the wood panels lining this small room, noticing how narrow it was, wondering where my sense of duty would take me.

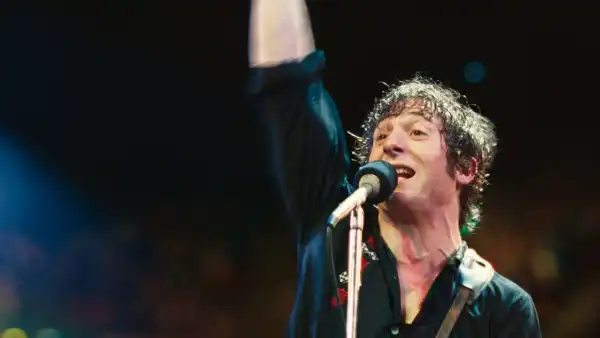

A group of high-achieving Asian-American high-school seniors dip into criminal activities in “Better Luck Tomorrow.”

Photograph from Entertainment Pictures / Alamy

Five years later, I was freelancing in Boston when “Better Luck Tomorrow,” Justin Lin’s film about Asian-American overachievers whose competitiveness eventually turns them toward crime, premièred at the Sundance Film Festival. After one screening, a white critic stood up and accused Lin and his cast of letting down their community with such a violent and, in his words, “amoral” portrayal of Asian-American life. Roger Ebert, among others, defended the movie, and “Better Luck Tomorrow,” which was eventually acquired by MTV Pictures for theatrical release, prompted a larger conversation about what responsibility a film and its audience have to one another. I felt for Lin and his cast, whose low-budget crime flick was suddenly given the weight of representing an entire community. They became fodder for endless discussions about whether bad representation—which could mean anything from gaudy stereotypes to a movie, like “Better Luck Tomorrow,” that was just O.K. but not great—was worse than no representation at all. It was a reminder that you don’t always get to choose the moment, or the cause, to rally behind.

As the film graduated from festivals to a national release, there were campaigns, particularly on college campuses, to insure it had a successful opening weekend. It was as though the movie’s partisans were mobilizing people to vote. I interviewed one of the film’s producers for the Village Voice about this grassroots movement, and as we wrapped up, he said it was great to have me “on the team.” As a journalist, I wasn’t sure if I could ever really be on their team or not. Still, I wanted them to flourish, even if I wasn’t sure what that would mean.

I thought about all of this in the run-up to “Crazy Rich Asians,” the director Jon M. Chu’s adaptation of Kevin Kwan’s best-selling novel. As every article about “Crazy Rich Asians” is obliged to mention, it is the first film from a major studio with a predominantly Asian-American cast since “The Joy Luck Club,” twenty-five years ago. In the past, the duty of representation could feel like a crushing, now-or-never burden. But the cast of “Crazy Rich Asians” seems emboldened by the challenge, and the campaign among fans to buy out screenings and get #GoldOpen trending has been explicit about turning opening-weekend box-office returns into politics by other means. (Those efforts helped the film reach the No. 1 spot this past weekend; it has made more than thirty-five million dollars in the U.S. so far.) That the film’s release has sparked debates about income inequality and immigrant communities, intra-Asian discrimination, and cultural appropriation speaks to how rare it is for an Asian-American product to become a spectacle shared with everyone else.

I watched it opening weekend, at a theatre that showed a mini-documentary about Asian-Americans in popular culture before the trailers. The mini-doc reminded viewers of disparaging Hollywood practices: white actors in “yellowface,” Asians cast only as inscrutable foreigners. It noted the previous glimpses of a possible but repeatedly stalled revolution: Wayne Wang’s breakthrough début, “Chan Is Missing,” his “Joy Luck Club” adaptation, Mira Nair’s “Mississippi Masala,” “Better Luck Tomorrow,” the “Harold and Kumar” franchise. When the trailers were over and “Crazy Rich Asians” began, it very quickly became clear that it was a polished and extremely savvy departure from this tradition, largely untroubled by the questions of authenticity and foreignness that dogged previous generations. The movie seems ready made for an increasingly global movie business, featuring stars already famous throughout America (Constance Wu), Europe (Henry Golding, Gemma Chan), and Asia (Michelle Yeoh). But amid the family-dysfunction slapstick and the haughty splendor I found myself moved by moments when very little was happening, the kinds of everyday moments that I’ve always wanted to see onscreen: friends eating at the night market, an elder slowly studying the face of a newcomer, the pained but sympathetic expression of a native speaker trying to decipher another’s rusty Mandarin. Maybe it’s the end point of representation—you simply want the opportunity to be as heroic, or funny, or petty, or goofy, or boring as everyone else.

A couple of years after I covered the Class of ‘97 for that Chinatown newspaper, my friend Eric told me he was making a film. We were both seniors at Berkeley, and our conversations about his script often branched off into riffs about Roman Polanski’s “Chinatown,” Chinese folktales, the latest issue of Giant Robot, the radiance of Hype Williams’s “Belly.” I was still living in the shadow of a tragedy it would take me years to get over, and I was often wary of going outdoors once the sun had set. But by making this movie he was defining a community, one that met every night of spring break—and I wanted to be a part of it. I would hang out on set, constantly looking over my shoulder. A tape of Sister Nancy’s “Bam Bam” and D’Angelo’s “Devil’s Pie” seemed on a perpetual loop. I got to play “Chinese Youth No. 3.” The only way you could distinguish me from the others in our little gang was that I dressed like a raver, and in one scene I got beat up. I was a terrible actor, and it had been months since I felt that good. After my scene was done, I remember running through the streets, no longer away from something, but into the San Francisco night, toward an uncertain light.

Sourse: newyorker.com