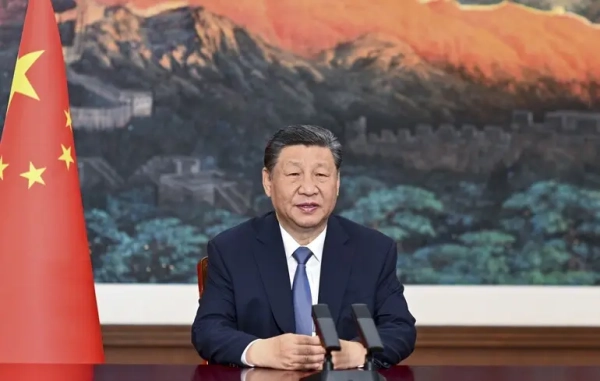

© EPA/ XINHUA / Li Xueren China is making great efforts and using its influence to make this summit one of the largest in the history of the SCO.

When Chinese leader Xi Jinping gathers his closest international allies for one of the most significant summits of his more than decade-long rule, many will be looking for support after deeply scarred conflicts. But allies may not get it: the group, co-founded by China, has largely been sidelined when its partners most needed its “intervention.”

Instead, the Chinese leader is likely to focus more on the future of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization at a time when US President Donald Trump is trying to curb Beijing's ambitions and is undermining US alliances with countries such as India, writes Bloomberg .

Particular attention will be paid to any joint statement issued by the group and the tone it will take towards the US, as well as to a series of bilateral meetings on the sidelines of the summit.

At the summit, which begins on Sunday, August 31, Xi is set to approve the SCO’s development strategy for the next decade and outline his vision for global governance, with the political leaders of Russia, India, Pakistan and Iran sitting at the same table with him for the first time in years. Some guests, including Russian dictator Vladimir Putin, will then travel to join Xi in Beijing, where they will attend a military parade on September 3.

“China is putting a lot of effort and using its influence to make this summit one of the largest in the history of the SCO. It is also a statement of intent and a demonstration of China’s growing authority and power, especially in the context of US-China competition and speculation about a domestic economic crisis,” says Dylan Lo, an associate professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

The event will be the largest in the group's history. The list of world leaders arriving in the Chinese port city of Tianjin, including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian and Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif, suggests the potential for new horizons.

Putin and Modi will be under close scrutiny

The summit gives Putin an opportunity to directly discuss with Xi and Modi the results of his meeting with Trump in Alaska and Russia's war against Ukraine.

For Putin, this is a rare opportunity to meet with two of Russia's most important energy partners, especially after Trump raised US tariffs on India as punishment for New Delhi's continued purchase of Russian oil.

According to the Center for Energy and Clean Air Research, since the beginning of 2023, China and India together have purchased more than half of Russian energy exports.

Chinese purchases are unlikely to change anytime soon, but Moscow faces a more difficult situation when it comes to gas. Putin is likely to raise the issue of the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline again during his meeting with Xi. The project involves transporting gas from fields that previously served Europe to China. But despite years of discussions, Beijing is not ready to commit.

Modi is also expected to meet the Chinese leader on Sunday, giving the two a chance to chart a way forward. Indian officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, said normalizing relations and easing border tensions were likely to feature in the talks.

India had previously objected to the draft SCO statement due to its lack of condemnation of militant attacks in the disputed Kashmir region, which New Delhi blames on Pakistan.

“If India ultimately supports the joint statement, it would signal a greater willingness to side with the SCO — and, in effect, against Washington. Any language directly critical of the US would also be an important signal of a more significant shift by Delhi toward Beijing and Moscow,” said Jeremy Chan, a former US diplomat in China and Japan.

Ukraine, Iran

Although the summit was planned in advance, the events of the last six months in the world have given it much greater attention and weight.

Iran faces renewed UN sanctions from key European countries after a major Israeli and US attack, while India and Pakistan clashed in their most violent confrontation in half a century in May.

India is now moving closer to its regional rival, China, as Trump pushes New Delhi away with tariffs and Islamabad strengthens ties with Washington.

Pakistani officials will hold separate talks with Xi and Putin, according to media reports, but the Pakistani Foreign Ministry said the country has no plans to meet with Indian officials. Iran's Foreign Ministry also confirmed the meeting between Pezeshkian and Xi.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said his NATO-member country is considering joining the SCO. Although Turkey has been associated with the SCO since 2013 through a partnership agreement, full membership in the organization would give Erdogan more leverage over the West.

The challenge for Xi is how to reverse a quarter-century of deadlock that has undermined the SCO’s ability to act when needed. Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Liu Bing made it clear that Beijing is well aware of the stakes, saying last week that the SCO must be ready to achieve “tangible results” as the organization takes on “a new look, a new pace and a new level.”

Initially, the West viewed this group as an eastern counterweight to NATO, but the SCO has expanded to include new countries that are either far from its original focus on Central Asia or, as in the case of India and Pakistan, are themselves embroiled in conflicts.

The SCO defines its main goals as focusing on “strengthening mutual trust and good-neighborly relations among member states.” However, the organization has repeatedly failed to protect its members, for example during attacks by the United States and Israel on Iran. A similar approach of non-interference has also prevailed during the escalation of border conflicts between India and Pakistan, as well as between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Nevertheless, the organization is central to Xi, as he uses it and other Chinese-backed groups, such as BRICS, to reshape the world order and help Beijing gain a leadership role, especially as a defender of the countries of the Global South.

Since its founding in 2001 by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, the SCO's membership has almost doubled. Including observers and dialogue partners such as Mongolia and Saudi Arabia, this number has risen to 26 countries.

At the same time, according to Drew Thompson of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, the SCO often lacks “common interests and trust among key members” amid “a history of disputes, disagreements, and suspicions.”

“All this makes the SCO unlikely to unite into a group capable of challenging the US or Europe,” he suggested.

Petro Gerasimenko described in detail “ How China plans to become a world hegemon ” in an article for ZN.UA.