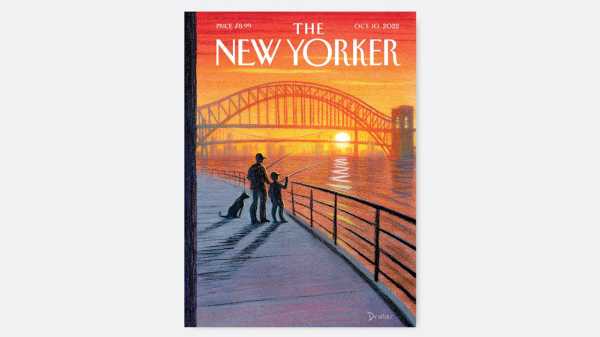

These days, the Hell Gate Bridge, which connects the Astoria neighborhood of Queens with Randall’s Island, is one of the more obscure New York City bridges, appreciated mostly by those who know it for being a good fishing spot. This was not always the case. When the bridge opened, in 1917, it was seen as a triumph of engineering. The steel-arch design inspired the engineers of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, in Australia, and the Tyne Bridge, in Newcastle, England. (In 1991, this magazine ran a piece chronicling how the bridge had faded over the years, literally as well as figuratively—the bridge’s paint had, because of years of neglect, flaked in patches.) I recently talked to the artist Eric Drooker, who depicted the bridge in his cover for the October 10, 2022, issue, about his love of picturesque views and the time he spent hanging out with fishermen as a child.

Do you have a particular relationship to bridges?

When I was a kid growing up in lower Manhattan, I was mesmerized by the wild variety of bridges around the city. Through my bedroom window, I could see the Brooklyn Bridge off in the distance, and, when I grew older, I would walk across to Brooklyn. My first-grade class also walked across the Wards Island Bridge, on 103rd Street, over the Harlem River. [No cars are allowed on it.] I was psyched when I realized most of the bridges have a pedestrian footpath.

Have you ever visited Hell Gate Bridge?

A few months ago, I went there for the first time. It always mystified me—spooked me a little. Hell Gate Bridge is named for the strait of water it crosses. Back in the colonial days of New Amsterdam, the treacherous currents and rocks in the area would pull sailors down to their watery graves. I wanted to study it, paint a picture of it. When I got there, I discovered that you can’t walk across it—you can’t even drive across it—it’s simply a railroad bridge. The water around the bridge is still not safe for swimming, but I hear the fishing there is excellent.

Did you go fishing yourself?

I used to go fishing a lot when I was a kid. There was a pond full of catfish and sunfish about an hour upstate, where I got really good at catching turtles with my bare hands. I enjoyed hanging out with the guys fishing in the East River. Once I saw this dude catch nothing but eels all day. He had a whole bucket full of squirming serpentlike creatures—totally freaked me out.

You now live in California, with its famous sunsets. Do you think New York City sunsets can compete?

New York’s sunsets were most spectacular in the nineteen-sixties, when the pollution was so thick, the sun looked like a colossal penny hanging in the air. Now, California sunsets are at their most sublime during wildfire season. Through the smoke, the sun looks like a glowing red-hot rubber ball.

See below for more covers featuring the city’s bridges:

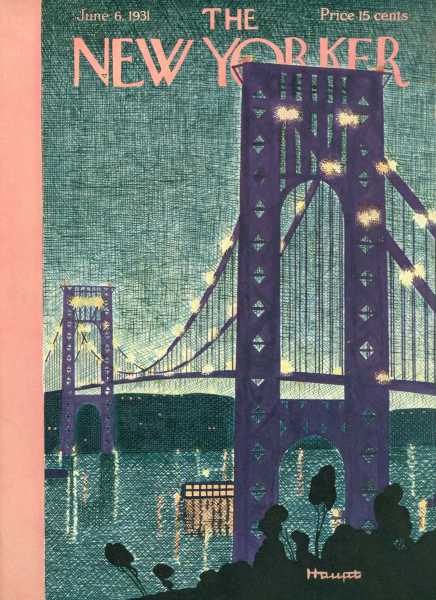

“June 6, 1931,” by Theodore G. Haupt

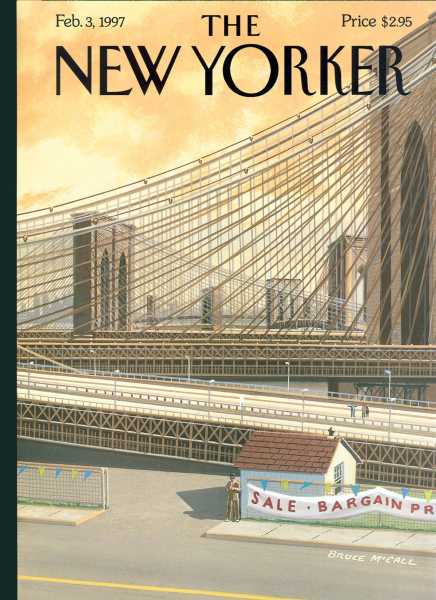

“February 3, 1997,” by Bruce McCall

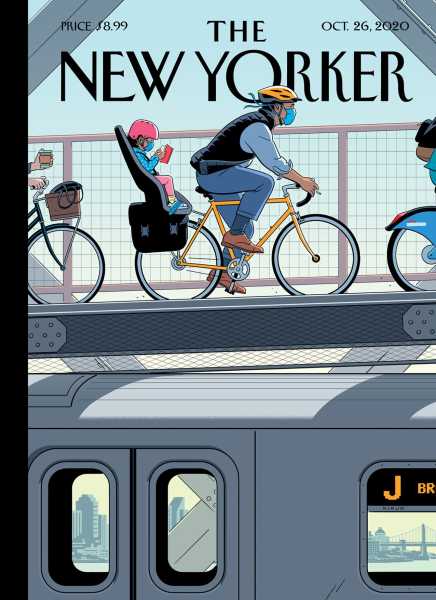

“Shifting Gears,” by R. Kikuo Johnson

Find Eric Drooker’s covers, cartoons, and more at the Condé Nast Store.

Sourse: newyorker.com