On August 12, 1963, Bob Dylan recorded a version of “The Moonshiner”—a dismal, repentant drinking song that’s been part of the American folk vernacular since at least the nineteen-thirties—at a session for his third LP, “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” The rendition is grim. (Dylan didn’t formally release the song until 1991, for the first installment of “The Bootleg Series,” an ongoing, multi-volume collection of rarities and live material.) His voice sounds particularly low and fragile on the first verse, as he describes an inevitable retreat into the mountains:

I go to some hollow,

And sit at my still

And if whiskey don’t kill me

Then I don’t know what will

Most versions of the song are mournful, if not bereft. I can’t think of a single iteration that doesn’t make me want to drink, and then feel deep shame about drinking. There’s Uncle Tupelo’s arrangement, from 1992, or Roscoe Holcomb and Wade Ward’s, from 1962, or Cat Power’s particularly gutting variant, from 1998 (“You’re already in Hell, you’re already in Hell, I wish we could go to Hell!,” she wails toward the end). The song seems to force its singers into a kind of funereal reckoning: life is simply too long and hard to bear sober. Cheers!

In his book “Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey,” the historian Michael R. Veach suggests that the bourbon industry itself offers a kind of parallel history of America, from the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791 through the Industrial Revolution and beyond: “Even the general health of the bourbon industry mirrors that of the country as a whole,” he writes. Dylan, too, can feel like an America in miniature: a nobody from Minnesota ventures East, reinvents himself, channels the Zeitgeist, makes it big. Perhaps Dylan is the true canary in America’s coal mine—each seemingly inscrutable move is merely a reflection of the national condition.

Now he has curated a series of American whiskeys. In 2015, Marc Bushala, the C.E.O. of Spirits Investment Partnership, and a former partner in Angel’s Envy bourbon, discovered that Dylan had registered a trademark application for a “bootleg whiskey.” He approached Dylan about realizing the idea, and their first three creations—a Tennessee bourbon, a blended double-barrel whiskey, and a straight rye whiskey, all with suggested prices of between fifty and eighty dollars a bottle—are available in select cities. That these have arrived during a season in which Americans are hungry for deliverance of any sort—even the kind that makes you want to eat an entire saucepan of macaroni and cheese, moaning feebly in the morning sun, a pillow still pressed to your face—feels in keeping with this mythos.

The collection is called Heaven’s Door, in a sly and enticing nod to “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” a song Dylan wrote, in 1973, for the Western “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” (a movie that, too, is mostly about dying). “I’ve been travelling for decades, and I’ve been able to try some of the best spirits that the world of whiskey has to offer,” Dylan said of the stuff. “This is great whiskey.”

The first three creations in the Heaven’s Door series—a blended double-barrel whiskey, a straight rye whiskey, and a Tennessee bourbon—are available in select cities.

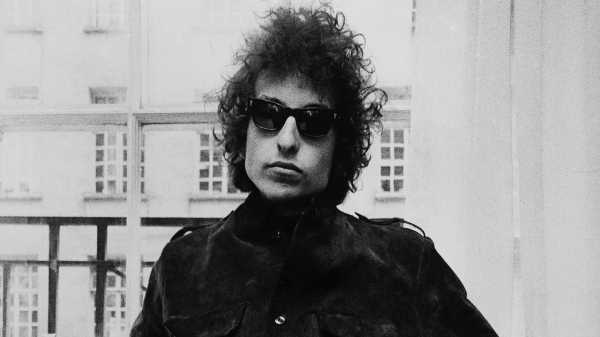

Photograph by Gab Bonghi / Heaven’s Door

In a promotional photo for the brand, Dylan sits in a worn leather chair, wearing a bespoke suit, peering at a hardcover book—surely a first edition—and clutching a glass of bourbon. (For me, the image inevitably evokes thoughts of “Suntory Time!,” the Japanese whiskey commercial that Bill Murray’s character films in “Lost in Translation.”) The Heaven’s Door labels feature thick iron gates, rendered in silhouette, which Dylan himself made in his ironworks studio, using “objects found on farms and scrap yards across America,” including a crow (on the Tennessee bourbon), a heel spur (on the rye), and a shovel (on the double-barrel whiskey). Together, they suggest real labor, capitulations to scabrous terrain, to work that requires spiritual as well as physical decompression—a drink to blur the edges, as the sun finally dips below the horizon.

Did I do anything difficult—hoe a field, corral some cattle, excavate minerals?—to earn my three glasses of Heaven’s Door? Of course not. Nonetheless, on a recent weekday evening, I plonked down a crystal tumbler, cracked a tray of ice, and prepared myself a sizable drink. (“God don’t like it, and I don’t either,” the Piedmont blues guitarist Blind Willie McTell and his singing partner, who was also his wife, announced in 1935, in a song about the many vagaries of moonshine—but such is how we get down to work here at The New Yorker.) Although appreciations of whiskey can feel fussy and leaden, the drink is rugged by design, and an efficient path toward a certain sort of self-obliteration. I will admit now that I tend toward the Raymond Chandler school of cocktail analysis, which is to say, “There is no bad whiskey. There are only some whiskeys that aren’t as good as others.” So I opted to use the professional tasting notes provided by the spirits experts David Wondrich and Heather Greene to pair each bottle with a complementary Dylan song, insuring a full and cohesive experience.

My first pour was the Tennessee bourbon, which I found sweet and light. “This whiskey is fun in that some of the secondary notes that one usually has to hunt around for are right up front,” Greene offers in her notes. “The pronounced hazelnut note on retro-nasal olfaction is really pleasant.” I scanned my record shelf. Dylan had never sung of hazelnuts, or of retro-nasal olfaction. But there’s a verse in “Huck’s Tune,” from 2007, that I’ve always liked:

I’m laying in the sand getting a sunshine tan,

Moving along, riding in style

From my toes to my head, you knock me dead,

I’m gonna have to put you down for a while

It is now my belief that those four lines fairly accurately track the experience of enjoying a generous serving of Dylan’s Tennessee bourbon. (“Sunshine tan” is also, incidentally, an odd and lovely way of describing the drink’s color). “Huck’s Tune” is full of wry, funny bits—things that a person might whisper into her cup: “You think I’m blue? I think so too,” Dylan sings later.

My second serving was the straight rye, which is distilled in Tennessee, but finished in toasted French oak barrels from the Vosges Mountains, near the German border. It was my favorite of the three releases—herbaceous, spicy, and sharp. I paired it with “Idiot Wind,” which is maybe the meanest song in Dylan’s discography (“You’re an idiot, babe / It’s a wonder that you still know how to breathe,” he sings). I prefer the so-called New York version of the song, which was recorded at A&R Recording Studios, on Seventh Avenue, in September of 1974, and features a few unexpected peals of organ. (Dylan eventually re-recorded much of “Blood on the Tracks” at Sound 80, in Minneapolis, before finally releasing it commercially.) In New York, Dylan sounds less sneering and more lost. Though he was going through a grievous divorce at the time, he has said that the record’s tales of thwarted, soured love weren’t autobiographical, but based on Anton Chekhov’s short stories. (Nobody believed him.) I drained my glass.

Wondrich describes the double-barrel whiskey, which was aged for more than seven years in American oak barrels, as having “a little alcohol to lead, followed by dusty, split wood, corn and coconut, with charcoal and even something like Memphis BBQ sauce developing late.” For my last pour, then, it seemed inevitable to cue up “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” from 1966’s “Blonde on Blonde.” Dylan recorded twenty different takes of the song that February, in Columbia’s Music Row Studios, in Nashville. But it’s a Memphis song in both spirit and content—scrappy, panicked, rollicking.

Everything now seemed rosy and warm. As a kind of palette cleanser, I put on Tommy McClennan’s “Whiskey Head Woman,” a cautionary blues from 1939:

’Cause you’s a whiskey-headed woman

An’ you stay drunk all the time

Now, if you don’t stop drinkin’

I believe you’re goin’ to lose your mind

It was time, I knew, to rinse my glass and retreat to bed. Perhaps next year will see the arrival of a much-needed Dylan-branded aspirin.

Sourse: newyorker.com