In recent years, on Instagram and in fashion magazines, a girl-centric aesthetic has taken hold. Young photographers such as Petra Collins, Olivia Bee, and Mayan Toledano have been capturing the private rites and practices of adolescents—in school, at parties, on road trips, alone in their bedrooms. The style, pretty and wistful, straddles fashion, fine art, even reportage. We might see a shapely young arm raised to reveal a hint of armpit hair; dewy skin dappled by disco lights; girls huddled around a mirror, putting on makeup.

Someone unfamiliar with the photographs of Justine Kurland might assume that the sixty-nine images that compose her “Girl Pictures,” currently on view at Mitchell-Innes & Nash gallery, were taken by one of Collins’s twentysomething peers. Kurland’s adolescents are messy-haired and free and lovely, smoking, hanging out in meadows or in parking lots, in forests or in playgrounds, enacting their own mysterious routines. But the images in “Girl Pictures” were shot between 1997 and 2002, and Kurland is part of an older generation of female artists who studied at Yale under Gregory Crewdson, another photographer known for his cinematic, highly staged pictures. Kurland, Dana Hoey, Katy Grannan, and Malerie Marder all achieved early recognition after taking part in the 1999 group show “Another Girl, Another Planet,” which anticipated our own era’s photography of the female gaze.

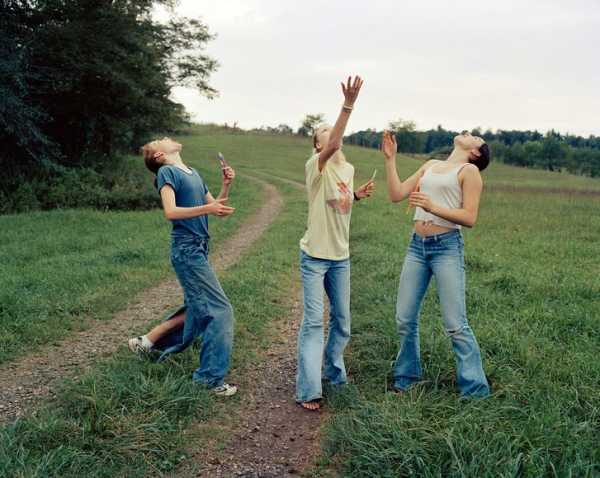

“Candy Toss,” 2000.

Like Collins, Kurland stages her tightly controlled compositions, but Kurland’s photographs are less dreamy, more menacing, charged with a feral sense of possibility. “I channeled the raw, angry energy of girl bands into my photographs of teenagers,” she writes in the monograph that accompanies the show. “All the power chords we would ever need lay within reach, latent, coiled in wait.” In one photograph, taken in 1999, a girl is kneeling in a tangle of weeds and wildflowers by the side of a road, her underpants rolled down to her knees, her arms holding back her skirt as she pees. Her face, turned downward, is lightly overlaid with blossoms of Queen Anne’s lace, the afternoon sunlight dappling her back and hair in a pacific, Vermeerian composition. Her squatting pose evokes a moment on the verge, a bird about to take flight; she is not just prey but huntress. In another image, two waifs explore a dark grove with the aid of a flashlight, their eyes wide with fear. And yet they keep on.

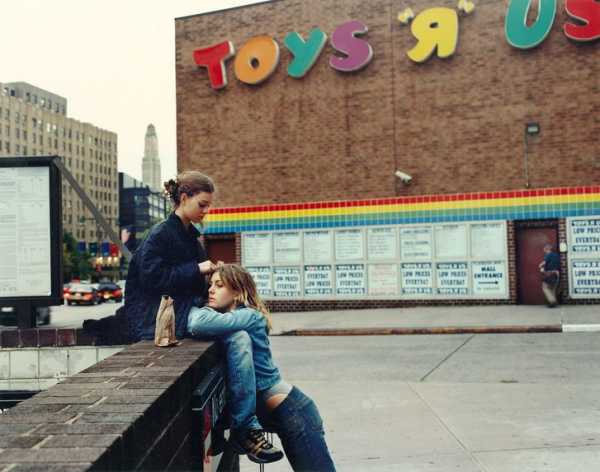

“Toys R Us,” 1998.

”Bathroom,” 1997.

Danger is always just around the corner in Kurland’s work. But what is this danger, exactly? We are used to the teen-age girl who is constitutionally imperilled by virtue of her vulnerable, sexual body. And while there is a rich cultural history of the adolescent who is terrifyingly impervious to the rules of adults—from Kubrick’s futuristic “Clockwork Orange” Droogs to Larry Clark’s spaced-out skaters in “Kids”—such representations rarely put young women front and center. In this way, Kurland’s images of lawless girls, whose menace is a form of power, are almost utopian. In one picture, two girls practice kung fu in a field below an overpass. They are observed by a third girl, halter-topped, sitting on a rock and blowing a large, pink gum bubble. She might seem passive, but she is following closely, awaiting her turn to train in the girl militia. Kurland, like Ryan McGinley after her, took most of her photographs while road-tripping, driving west. Unlike McGinley, who travelled with a group of muses whom he photographed, Kurland’s expeditions were solitary, and her photographs, too, channel an independence of spirit rather than a group mentality. She scouted teens to choreograph wherever she stopped, and the girls, she writes, “went home after we made photographs, while I kept driving.”

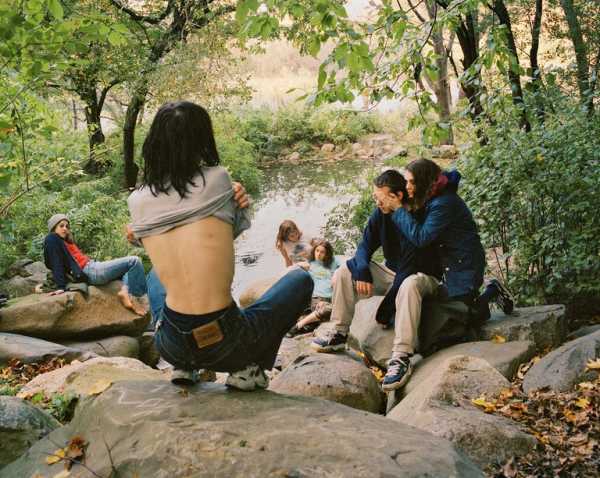

“Boy Torture: Love,” 1999.

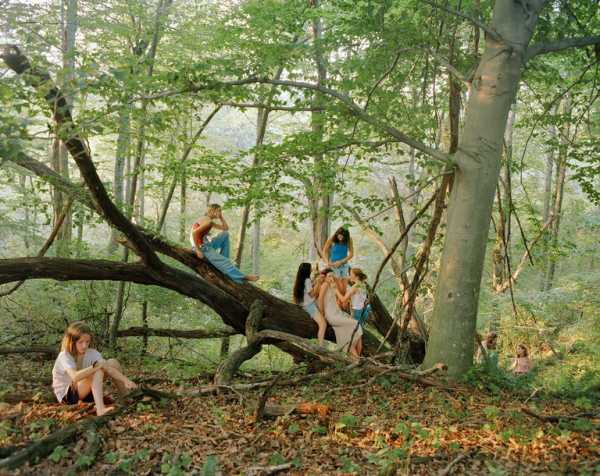

I noticed that, in a number of photos, the teens handle dead animals: two girls carry the body of an elk tied to a stout stick across a creek; a group of mud-stained urchins prepares an armadillo for burial; a girl holds a dead bird by its neck as she trudges down the side of a highway. These girls are Huck Finns in Gap jeans and tank tops and ponytails, exploring an America both grimy and sublime, a country where, to survive, violence must be treated with nonchalance. In another image, three girls gather in front of what looks like a rest-stop-bathroom mirror. One is smoking and reading a magazine, the second casually shirtless, the third casually pantsless. Involved in their own world, they look at each other, uninterested in us. They are a coven in repose. Who knows what they’ll do once we turn our gaze away?

“Superstitious Mountain,” 1999.

“Forest,” 1998.

“Respite Under the Bridge,” 1998.

“Armadillo Burial,” 2001.

“Kung Fu Fighters,” 1999.

”One Red, One Blue,” 2001.

”Dairy Queen,” 2000.

“Forest Fire,” 2000.

”Curtsy,” 1999.

”Snow Angels,” 2000.

Sourse: newyorker.com