9 essential lessons from psychology to understand the Trump era

Motivated reasoning, bias, fake news, conspiracy theories, and more, explained.

By

Brian Resnick@B_resnick

Updated

Apr 25, 2018, 10:36am EDT

Graphics and Illustrations by Javier Zarracina

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

9 essential lessons from psychology to understand the Trump era

tweet

share

In January 2017, when then-White House press secretary Sean Spicer tried to claim that President Donald Trump’s inauguration was the most-watched in history, it felt like the beginning of a new, dark era of politics and public life.

As it has matured, the Trump era of conservative politics is increasingly defined by its tribalism and fear and the fracturing of our sense of a shared reality.

And it’s pretty disorienting.

I’ve spent much of the past several years reporting on political psychology, asking the country’s foremost experts on human behavior some variation of, “What the hell is going on in the United States?”

Thankfully, at a time when we really need answers, they often deliver.

Here are the social science lessons I keep coming back to, to help me explain what’s happening in America in the Trump era. Perhaps you’ll find them helpful too.

- Rooting for a team alters your perception of the world.

- We can be immune to uncomfortable facts.

- Leaders like Trump have special powers to sway public opinion.

- People don’t often make decisions based on the truth.

- Political opponents are often really, really bad at arguing with one another.

- White people’s fear of being replaced is incredibly powerful.

- It’s shockingly easy to grow numb to mass suffering.

- Fake news preys on our biases — and will be very hard to stamp out.

- Conspiracy theories may be rampant, but they’re a specific reaction to a dark, uncertain world.

An uncomfortable theme you might notice here is that our leaders, the groups we were born into, and, increasingly, our echo-chambered media ecosystems can bring out the worst psychological biases that exist in all of us.

In other words, no one, be they Democrat or Republican, is inherently stupid. “At the end of the day, we’re all human beings and we use the same psychological processes,” Dominique Brossard, a communications researcher at the University of Wisconsin Madison, recently told me.

Consider this a primer on what current events and politics can bring out in the human mind. And be warned: It’s not always pretty.

A version of this piece originally published in March 2017. This has been updated to reflect current events, new studies, and other reporting I’ve done since then.

1) Motivated reasoning: rooting for a team changes your perception of the world

Psychology has been called “the hardest science” because the human mind comes with so many messy inconsistencies. Even the best researchers can get tangled up in them. What’s more, it can take decades to establish a psychological theory, which could be torn down in a month with new evidence. But despite its flaws, psychology is still the best scientific tool we have to understand human behavior.

The key psychological concept for understanding politics, and one of the oldest, is motivated cognition, or motivated reasoning. It often means that rooting for a team alters our perception of reality.

In the 1950s, psychologists noted how fans of two football teams came to very different conclusions about who was at fault for rough play, despite the fact that the fans were watching the exact same footage. The psychologists concluded it was like the two sets of fans were watching a different game.

Our teams are lenses through which we interpret the world. In a more recent experiment, researchers showed participants a video of a protest that had been halted by the police. Half the subjects were told the protest was of an abortion clinic. The other half were told it was a protest against the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

People inclined to support abortion rights thought the protesters were more disruptive in the abortion clinic condition. People who had strong egalitarian ideals were more likely to express support for the protesters for LGBTQ rights. Again, it was the same exact footage. All the changed were who the participants thought the protesters were.

One crucial thing to know about motivated reasoning is that you often don’t realize you’re doing it. We’re quicker to recognize information that confirms what we already know, which makes us blind to facts that discount it.

Which is perhaps why being on a team makes us more susceptible to believing in and remembering false news stories. In a 2013 study, liberals were more likely to (falsely) remember President George W. Bush being on vacation with a celebrity during the Hurricane Katrina disaster in 2005. Conservatives were more likely to say they remembered President Barack Obama shaking hands with the president of Iran (which never happened).

And it can cause us to rationalize the logically absurd. Consider how the head of the conservative Family Research Council suggest Trump should get a “mulligan” for his alleged affair with a porn actress.

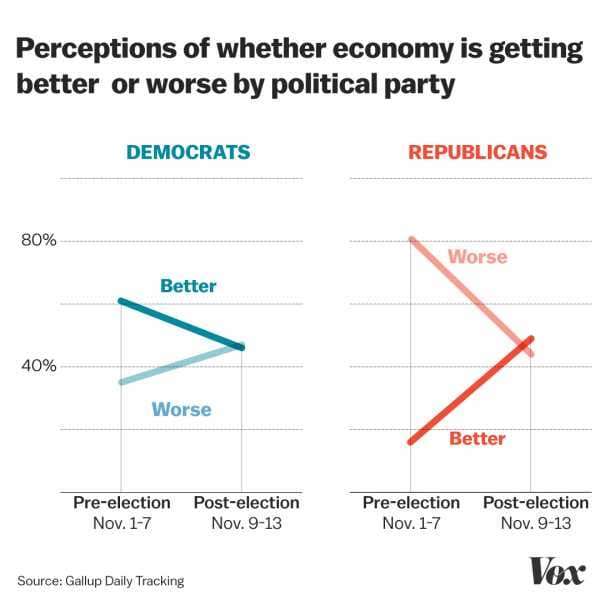

When the status of our teams changes, so do our opinions. When Gallup polled Americans the week before and the week after the presidential election, Democrats and Republicans flipped their perceptions of the economy, even though nothing had actually changed about the economy. What changed was which team was winning. The economic prospects of the country suddenly looked a lot better for Republicans once their candidate won.

We’re so prone to seeing the world in terms of us versus them that psychologists start seeing people exhibit group bias when they’re randomly sorted into arbitrary “blue” teams and “red” teams in an experiment.

But the fact that our group preferences are so quickly formed means they’re also easily changed: We start to view people in a more positive light if we start to view them as a compatriot. “We’re not hardwired to hate or [be] hostile to out-groups,” says Mina Cikara, a neuroscientist who studies intergroup bias at Harvard University. “All of these processes are flexible.”

2) Evolution has likely left us with an ideological immune system that fights off uncomfortable thoughts

There’s a reason we engage in motivated reasoning, a reason facts often don’t matter: evolution.

The human mind is a clever tool. We’ve used it to send rockets to the moon, and to invent wondrous things like pizza and air conditioning. But why did we evolve such cleverness in the first place?

One hypothesis: We became so smart to to be able to cooperate in groups. We’ve since adapted these skills to make breakthroughs in topics like science and math. But when pressed, we default to using our powers of mind to protect our groups.

In this light, motivated reasoning is an adaptation that helps bond us to others and aids our survival. It helps our group members share a common reality. It guides us to favor the people we see as “us” and shun people we see as “them.”

It also forces us to avoid uncomfortable facts that could harm our groups. You can see this immune system working in action. It’s a “motivated ignorance,” and psychologists can see it work in real time.

A 2017 experiment published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology presented partisan participants with two options. They could either read and answer questions about an opinion they agreed with — the topic was same-sex marriage — or read the opposing viewpoint. If the participants chose to read the opinion they agreed with, they were entered into a raffle pool to earn $7. If they selected to read the opposing opinion, they had a chance to win $10.

You’d think everyone would want to win more money, right? More money is better than less money.

No. A majority — 63 percent — of the participants chose to stick with what they already knew, forgoing the chance to win $10. “They don’t know what’s going on the other side, and they don’t want to know,” Jeremy Frimer, the University of Winnipeg psychologist who led the study, said in an interview.

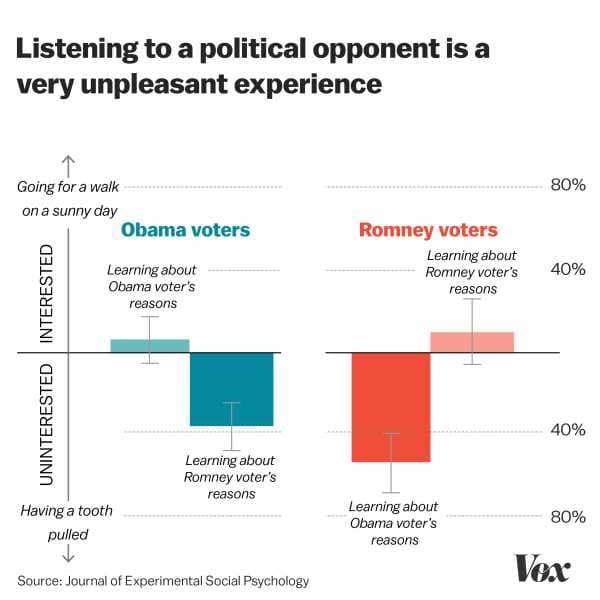

In another test, Frimer and colleagues essentially asked participants to rate how interested they were in learning about alternative political viewpoints compared to activities like “watching paint dry,” “sitting quietly,” “going for a walk on a sunny day,” and “having a tooth pulled.”

The results: Listening to a political opponent isn’t as awful as getting a tooth pulled, but it’s trending in that direction. It’s certainly a lot more awful than taking a leisurely stroll.

This is a key point that many people miss when discussing the “fake news” or “filter bubble” problem in our online media ecosystems. Avoiding facts inconvenient to our worldview isn’t just some passive, unconscious habit we engage in. We do it because we find these facts to be genuinely unpleasant. They insult our groups and, by extension, us. So we reject these facts, like our immune system would reject a pathogen.

“The brain’s primary responsibility is to take care of the body, to protect the body,” Jonas Kaplan, a psychologist at the University of Southern California, said in a 2017 interview. “The psychological self is the brain’s extension of that. When our self feels attacked, our [brain is] going to bring to bear the same defenses that it has for protecting the body.”

And here’s a final sticking point that keeps people away from facts. It’s often not the facts themselves that people fear and avoid. It’s where they lead.

This is called “solution aversion,” and it helps explain why many conservatives are wary of the science of climate change; many solutions to climate change involve increasing government oversight and regulations. Similarly, perhaps, this is why so many Trump supporters discredict the FBI’s investigation of Russian meddling. The possible conclusion — that Trump’s election was doctored by outside influences — is unsettling.

3) Leaders like Trump have enormous power to sway public opinion

We’re motivated to believe what our groups believe. In the Trump era, that has yielded some stunning shifts in public opinion.

Most notably, the rise of Donald Trump has coincided with some remarkable changes of mind among Republicans.

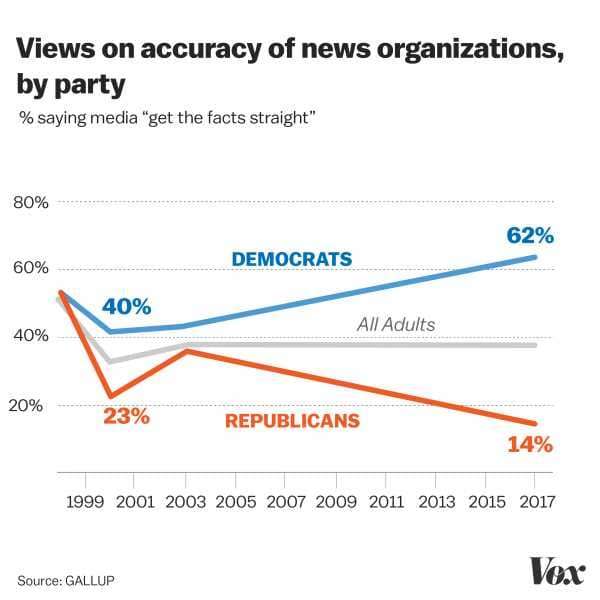

In 2015, just 12 percent of Republicans held a favorable view of Russian President Vladimir Putin, according to Gallup. In February 2017, the firm found 32 percent of Republicans liked him, despite mounting concerns that Russia had run a campaign to influence the election.

In 2014, according to a YouGov poll, 9 percent of Republicans considered Russia to be a friend or ally to the United States. In early 2018, that figure was 23 percent.

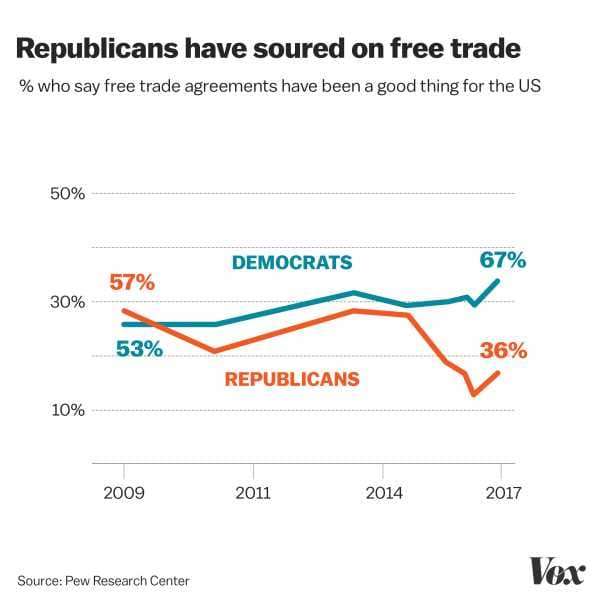

Or take the issue of free trade: Historically, conservatives have been in favor of it. But from 2015 to 2017, Republican support of free trade dropped from 56 percent in 2015 to just 36 percent in 2017, according to Pew.

Researchers have long wondered whether strong shifts in public opinion come from the top down: that partisans simply follow their leaders cues on issues. Or from the bottom up: that leaders try to reflect their followers’ ideology. The Trump era has given us some good evidence that the “follow the leader” effect is real.

In January 2017, two Brigham Young University political scientists designed an experiment to take advantage of the fact that, aside from a few issues like immigration, trade, and a reluctance to disparage Russia, Trump has few consistent policy ideas. They wondered: Will Trump supporters follow him wherever his policy whims go? So right after the inauguration, they ran an online experiment with 1,300 Republicans.

The study was pretty simple. Participants were asked to rate whether they supported or opposed policies like a higher minimum wage, the nuclear agreement with Iran, restrictions on abortion access, background checks for gun owners, and so on.

One-third of the participants read statements where they were told Trump supported a liberal position, like this:

The control group of the experiment saw these questions, but they didn’t mention Trump. Another arm of the experiments tested what happened when Trump was said to support conservative policies.

When participants were told Trump supported a liberal policy, Trump supporters were more likely to support it too. They followed their leader. “The conclusion we should draw is that the public, the average Republican sitting out there in America, is not going to stop Trump from doing whatever he wants,” Jeremy Pope, a co-author of the study, said. The effect even held true on questions about immigration. If Trump supported a lax immigration policy, his supporters said they did too.

Past experiments with liberal participants have found a similar effect: Liberals are more likely to support conservative policies when told their leaders support conservative policies. And it’s possible that when people are changing their minds in this manner, they’re not even aware their minds are changing.

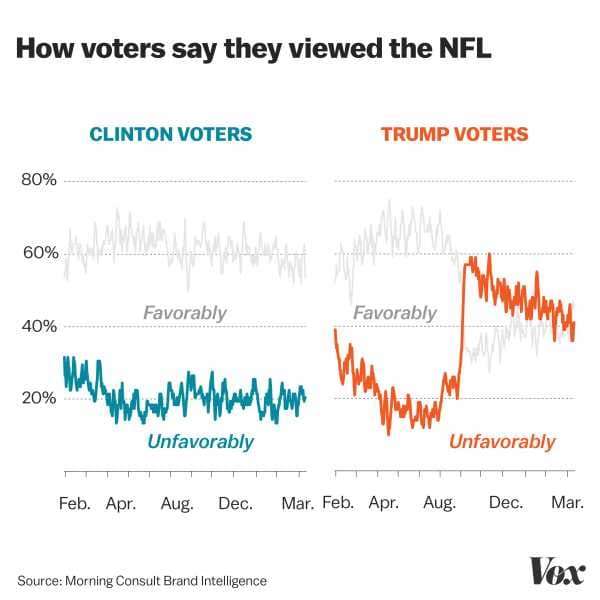

You don’t have to look too far in the news to know Trump is particularly adept at polarizing the public. Just look at what happened when he started going after NFL teams and players this past fall for kneeling during the national anthem. Nearly overnight, Trump supporters began to express strong negative feelings about the league. Yes, that’s conservative Americans expressing a dislike of football. Hard to imagine in a previous time.

The takeaway from all of this: Even though Trump remains a largely unpopular president, he still has enormous power to influence the opinions of millions of people who support him.

But it’s also important to not overstate how powerful an effect this is in the mind of Trump voters. It’s not like they’ve been totally brainwashed, their prior convictions replaced with the whims of their leader.

The truth is that many people don’t think all that often, or all that deeply, about policy (except for you, dear Vox reader). When we’re confronted with a hard question like, “What do I think about tax policy,” we often substitute it for an easier question: “What might leaders of my party say about tax policy?”

It’s a cognitive shortcut. And we all use them.

“These shortcuts can be political ideology; it could be religiosity, deference to scientific authority,” says Dominique Brossard, the University of Wisconsin communications researcher. “We defer to organizations and institutions to make sense of things for us.”

Remember, you can be both biased — say, predisposed to believe climate scientists on global warming — and correct.

4) People can understand inconvenient facts. But it’s very hard to make them matter.

Here’s some good news: It’s possible to use fact-checking to nudge people to believe in the truth. Here’s the bad news: People don’t make decisions based on facts.

In a recent experiment, political scientist Brendan Nyhan and colleagues found that Trump supporters were willing to admit Trump misrepresents facts. “But it didn’t have much of an effect on what they felt about him,” Nyhan says.

So facts can sink in, but they don’t always change our behavior and opinions. Let that sink in.

In fact, studies find that people who know more facts about politics are more likely to be stubborn and partisan. We don’t use our smarts to get at the truth. Instead, “people are using their reason to be socially competent actors,” says Dan Kahan, a psychologist at Yale. Put another way: We have a lot of pressure to live up to our groups’ expectations. And the smarter we are, the more we put our brain power to use for that end.

In his studies, Kahan will often give participants different kinds of math problems.

When the problem is about nonpolitical issues, like figuring out whether a drug is effective, people tend to use their math skills to solve it. But when they’re evaluating something political — let’s say, the effectiveness of gun control measures — math knowledge no longer matters. On these political questions, math knowledge actually makes it more likely for partisans to be biased. “The smarter the person is, the dumber politics can make them,” Ezra Klein explained in a profile of Kahan’s work.

And it’s not just for math problems: Kahan finds that Republicans who have higher levels of scientific knowledge are more stubborn when it comes to questions about climate change. The pattern is consistent: The more information we have, the more we bend it to serve our political aims.

This is another point where the debate over “fake news” is misguided: It’s not the case that if only people had perfectly true information, everyone would suddenly agree.

5) It’s really hard to change political opponents’ minds by arguing with them

The answer to polarization and political division is not simply exposing people to another point of view.

Recently, researchers at Duke, NYU, and Princeton ran an experiment where they paid a large sample of Democratic and Republican Twitter users to read more opinions from the other side. “We found no evidence that inter-group contact on social media reduces political polarization,” the authors wrote. Republicans in the experiment actually grew more conservative over the course of the test. Liberals in the experiment grew very slightly more liberal.

A psychological theory called “moral foundations” can help explain why our arguments often fail spectacularly at changing minds.

Moral foundations is the idea that people have stable, gut-level morals that influence their worldview. The liberal moral foundations include equality, fairness, and protection of the vulnerable. Conservative moral foundations favor in-group loyalty, moral purity, and respect for authority.

Moral foundations explain why messages highlighting equality and fairness resonate with liberals and why more patriotic messages like “make America great again” get some conservative hearts pumping.

Consider the unending gun control debate. Liberals make their arguments for restricting access in terms of protecting the vulnerable, and injustice (i.e., it’s not right that so many Americans have to live in fear of gun violence). Conservatives, meanwhile, ground their case in self-determination (i.e., I ought to be able to protect myself).

The thing is, we often don’t realize that people have moral foundations different from our own. When we engage in political debates, we all tend to overrate the power of arguments we find personally convincing — and wrongly think the other side will be swayed.

In a study, psychologists Robb Willer and Matthew Feinberg had around 200 conservative and liberal study participants write essays to sway political opponents on the acceptance of same-sex marriage or to make English the official language of the United States.

Almost all the participants made the same mistake.

Only 9 percent of the liberals in the study made arguments that reflected conservative moral principles; only 8 percent of the conservatives made arguments that had a chance of swaying a liberal. No wonder it’s so hard to change another person’s mind.

The bottom line: It helps to be empathetic when arguing with another person.

6) White people’s fear of being replaced is a powerful motivator

Last August, the white supremacists marching in Charlottesville, Virginia, were not ashamed when they shouted, “You will not replace us,” and, “Jews will not replace us.”

On the face of it, their fear — replacement — is absurd. White people (particularly white men) have been the dominant political and economic class of Americans from before this country’s founding.

But they actually do seem to feel this way. In April 2017, a team of psychologists got a sample of 447 self-identified alt-righters (though not those involved in the Charlottesville rally) in an online survey and led them through a barrage of psychological survey questions. They then compared the alt-righters to an online sample of 382 non-alt-righters.

The survey revealed that the alt-righters were much more concerned that their in-groups were at a disadvantage, compared to the control sample. The alt-right is afraid of being displaced by increasing numbers of immigrants and outsiders in this country. Yes, they see themselves as potential victims.

It’s easy to think these fears are abhorrent and confined to just people on the fringe. But they also do exist, to a smaller degree, among the mainstream, and among people who might not consider themselves to be racist.

These fears of outsiders, fears of replacement, and racial animus have become a powerful political instigator. Forty-one percent of white millennials voted for Trump. And among this group, political scientists find that a feeling that white people are losing out to other races is prevalent. “White millennials who scored high on the white vulnerability scale were 74 percent more likely to vote for Trump than those at the bottom of the scale,” political scientists Matthew Fowler, Vladimir E. Medenica, and, Cathy J. Cohen explain of their results in the Washington Post.

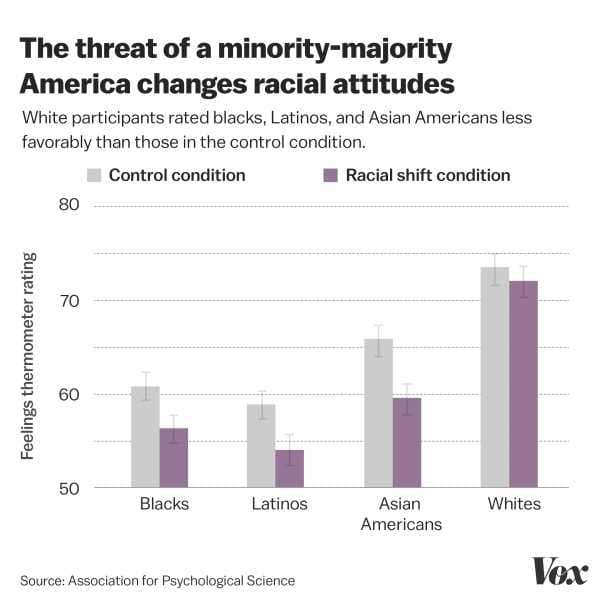

In experiments, when white participants are reminded that a majority of Americans will belong to minority groups in just a few decades, they begin to feel less warm toward members of other races. One test even showed that reminding white people of this trend increased support for Trump.

“People who think of themselves as not prejudiced (and liberal) demonstrate these threat effects,” said Jennifer Richeson, a leading researcher on racial bias who has conducted much of this research.

When people hear of one group rising in numbers, “a sense of a zero-sum competition between groups is activated,” Maureen Craig, who has collaborated with Richeson, says. When people hear about the rise of one group, they automatically fear it will mean a decline in their own. This happens even in well-intentioned people.

What this doesn’t mean is that all white people harbor extreme racial animus. It means fear is an all-too-easy button for politicians to press. We fear unthinkingly. It directs our actions. And it nudges us to believe the person who says he will vanquish our fears.

There’s also this fact to contend with: Negative, scary information is almost always more sticky and memorable than positive information.

And we tend to exaggerate the threat of people we don’t like. A 2012 paper nicely demonstrates this. The test was simple: The researchers asked participants to estimate the straight-line distance from New York to Mexico City. Participants who expressed more animosity toward Mexican immigrants rated Mexico City as being several hundred miles closer to New York than people who felt less threatened. The adversaries, in their minds, appeared to be much closer than they actually were. If people think the wall between the countries is secure, the effect goes away.

Savvy politicians understand that fear is motivating, and craft messages that stoke it. It’s hard to blame people for being afraid, and ideas like border walls might make them feel a bit more at ease. It’s just in our nature. But you can blame politicians who prey on it.

7) It’s shockingly easy to grow numb to the suffering of others

You might think that every time we see a shooting death or we’re reminded that there are millions of refugees and displaced people around the world, we’d all feel greater and greater empathy, and greater and greater sadness.

But no. It’s human to feel numb over time.

There’s a profound and infuriating psychological concept that can help explain increasing numbness in the face of long, slow-burning tragedy like mass gun violence in America. It’s this: As the number of victims in a tragedy increases, our empathy, our willingness to do something, reliably decreases.

This tendency is called psychic numbing. It describes how tragedies turn into abstractions in our minds, and how abstractions are easily attenuated and even ignored.

“There is no constant value for a human life,” University of Oregon psychologist Paul Slovic, the leading expert on psychic numbing, said in an interview. “The value of a single life diminishes against the backdrop of a larger tragedy.”

One of his recent studies demonstrated this simply. Slovic and his colleagues asked participants how willing they would be to donate money to children in need. And all it took was raising the number of victims from one to two to see a decrease in empathy and donations to the children.

In another experiment, Slovic found participants were less likely to act on behalf of 4,500 lives in a refugee camp if the camp had 250,000 inhabitants than if it had 11,000, even though 4,500 lives should be as important in any context. It’s infuriating.

“The feeling system doesn’t really add,” Slovic explains. “It can’t multiply; it doesn’t handle numbers very well.”

That’s why it’s not surprising six out of 10 Americans support a travel ban that, in part, bars refugees from entering America. That many lawmakers aren’t horrified by the possibility of booting tens of millions from health insurance. That the world looked on as millions died in war and genocide in Darfur. That we haven’t really grappled as a nation with the opioid epidemic, which killed 33,000 people in 2015.

It’s not surprising why political leaders often turn a blind eye toward refugees, or grow callous when it comes to the hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants brought to the US as children.

8) Fake news preys on our biases — and will be incredibly hard to stamp out

Hoaxes, conspiracy theories, and fabricated news are nothing new in human history. But today, aided by social media, they spread at alarming speed. And they have terrifying consequences.

Fake news is so pernicious because it preys on our biases. “Fake news is perfect for spreadability: It’s going to be shocking, it’s going to be surprising, and it’s going to be playing on people’s emotions, and that’s a recipe for how to spread misinformation,” Miriam Metzger, a UC Santa Barbara communications researcher, says.

After tragedies like the Parkland, Florida, school shooting or the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, we’ve seen false news stories and rumors spread on social media at a frightening speed — often outpacing the truth.

Recently, the journal Science published a study validating that feeling — at least when it comes to the spread of misinformation on Twitter. The study analyzed millions of tweets sent between 2006 and 2017 and came to a chilling conclusion: “Falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information.” It also found that “the effects were more pronounced for false political news than for false news about terrorism, natural disasters, science, urban legends, or financial information.”

But perhaps even more important is what the study reveals about what’s responsible for fueling the momentum of false news stories. It’s not influential Twitter accounts with millions of followers, or Russian bots designed to automatically tweet misinformation. It’s ordinary Twitter users, with meager followings, most likely just sharing the false news stories with their friends. And it’s perhaps due to a simple reason: False stories are often more surprising than real stories.

What’s frustrating is that algorithms like YouTube’s recommended video feed, or Facebook’s newsfeed, or Google News, often promote false stories (perhaps in part because we tend to find this content engaging).

But each time a reader encounters one of these stories on Facebook, Google, or really anywhere, it makes a subtle impression. Each time, the story grows more familiar. And that familiarity casts the illusion of truth.

Psychologists call this the illusory truth effect. It’s the simple finding that the more often a lie is repeated, the more likely it is to be believed.

When you’re hearing something for the second or third time, your brain becomes faster to respond to it. “And your brain misattributes that fluency as a signal for it being true,” says Lisa Fazio, a psychologist who studies learning and memory at Vanderbilt University. The more you hear something, the more “you’ll have this gut-level feeling that maybe it’s true.”

9) Conspiracy theories may be rampant — but they’re a specific reaction to a dark, uncertain world

Perhaps the darkest consequence of our strange age, where human psychology mashes up against hyperpartisanship and social algorithm-driven media distribution, is how conspiracy theories — often cruel, damaging ones — so easily circulate.

Shortly after the school shooting in Parkland left 17 dead, the No. 1 trending video on YouTube was based on a lie. The video alleged that David Hogg — a 17-year-old survivor of the Parkland shooting, who had become a compelling and sympathetic proponent of gun control, making the rounds on cable news — was an actor.

The pain inflicted by conspiracy theories can be immense: To this day, parents of children slain in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting are charged with making up the whole thing (including the lives of their children), for example.

Consider the agony of the family of Seth Rich, the Democratic Nationally Committee staffer who was murdered in an apparent robbery attempt in 2016. Despite zero evidence, conspiracy theorists and prominent conservative pundits have been fanning the suspicion that Rich’s murder was orchestrated by the Clinton campaign. “Seth’s death has been turned into a political football,” Rich’s parents wrote at the Washington Post. “Every day we wake up to new headlines, new lies, new factual errors, new people approaching us to take advantage of us and Seth’s legacy.” (And rest assured, conspiracy theories spread on the left too.)

Arguably, Trump — who for years boosted the conspiracy theory that Barack Obama was not born in the United States — adds flames to this fire. “Trump, in trying to combat the media, delegitimized the media, and has created an environment in which conspiracy theory is normalized,” Asheley Landrum, a Texas Tech University psychologist who studied motivated reasoning, told me in December.

Conspiracy theories are a type of motivated reasoning, Landrum explains. After the Parkland shooting, conspiracy theories that the teenage survivors were actors could, presumably, undercut their powerful anti-gun message.

But there’s also a more empathetic way to view conspiracy theorists: “It’s a self-protective mechanism people have,” Jan-Willem van Prooijen, a psychologist who studies conspiracy theories, told me last year. The theories are a tool by which people can feel more in control and find explanations in a scary and turbulent world.

People who feel powerless and who are more pessimistic are also more likely to believe in conspiracy theories, van Prooijen finds. And this is where education and outreach can help. Achieving higher levels of education correlates to feeling more secure about the world, and this, in turn, seems to protect against a conspiratorial mindset.

The thought of kids being gunned down at school is horrible. Why wouldn’t we seek refuge in a theory that insists it wasn’t so bad after all?

Further reading: political psychology in the age of Trump

You’ve just read more than 5,000 words on political psychology! Wow. Congrats! I’m impressed.

But if you want to read a few thousand more, here’s what I recommend:

- NYU psychologists Jay Van Bavel and Andrea Pereira have a great, easy-to-read academic explainer on how our political identities shape our beliefs. Follow the citations in this article and learn nearly everything there is to know about political psychology.

- Racial bias isn’t always subdued and implicit. It’s often explicit, and people are not ashamed of it. The psychology of dehumanization helps explain racial animus. Researchers Nour Kteily and Emile Bruneau find in their work that literally thinking of some racial groups as less than human is uncomfortably common in America.

- Ezra Klein’s How politics makes us stupid was one of the first pieces published at Vox, and it’s still relevant. In it, he discusses Dan Kahan’s work on how we use our intellect to benefit our groups, not the truth.

- After Trump’s election, America may have grown coarser, meaner. At the New Yorker, Maria Konnikova explains how societal norms change.

- Vox’s German Lopez sums up the evidence that racial resentment was a key factor in Trump’s victory.

- Lopez also has a great, thorough discussion on ways to reduce racial bias.

- And finally: Political persuasion is very hard. But it’s not impossible. Here are two promising efforts that show it’s possible to reduce bias.

Sourse: vox.com