In September, 1973, just a few days after General Augusto Pinochet staged a violent coup in Santiago, the photographer Evandro Teixeira, who had spent the previous decade covering the military regime in Brazil, was sent to Chile. “Of course, the hook was that bastard Pinochet, but otherwise we had to wing it, find our own way,” Teixeira, who’s now eighty-seven, told me recently. Teixeira, accompanied by a colleague from one of Brazil’s major daily papers at the time, the Jornal do Brasil, stayed at the old Hotel Carrera, right by the bombed Presidential palace, La Moneda. He ate and drank at the hotel bar after curfew, chatting with other guests and staying tuned to gossip and rumors, trying to get a sense of what was going on. The trip lasted only a few days, but it became one of the most important of his career.

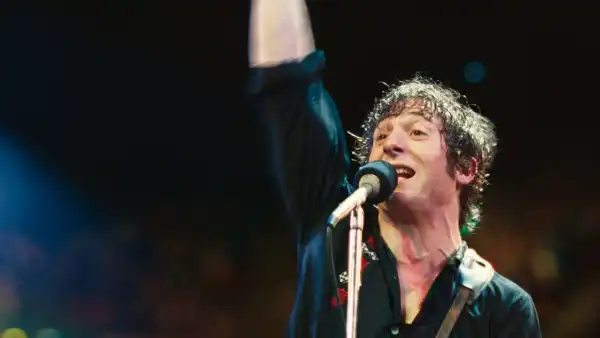

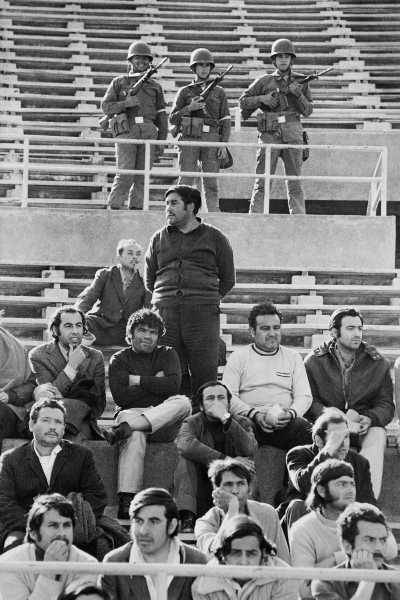

One day, he went to the Estadio Nacional, a grand soccer stadium in Santiago. Pinochet’s newly installed government had quartered prisoners there, and was allowing members of the press to visit. The intention, according to Teixeira, was to show that the people detained were not being mistreated. Men sat in the stands, staring out at the field, surrounded by soldiers. “Those were some poor old souls,” Teixeira said. He had visited the same place roughly a decade before, in 1962, for the World Cup, and, based on a vague memory of the stadium’s architecture, he intuited that there were other detainees elsewhere. “I knew the important prisoners were being held in the basement,” he said. He took pictures of the men in the stands, but he also managed to find small cells, more like cages, where men were cramped together.

Political prisoners held by the military at the Estadio Nacional, Santiago, Chile, September 22, 1973.

Political prisoners incarcerated underground at the Estadio Nacional. This photo was published in the Jornal do Brasil, in 1973.

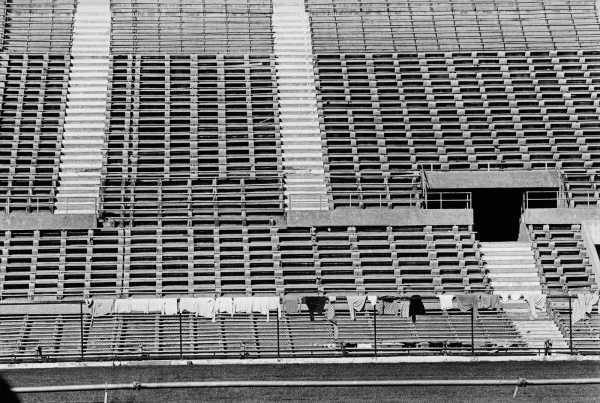

Estadio Nacional, Santiago, Chile, September 22, 1973.

Teixeira’s photos in Chile are the main subject of a retrospective at the Instituto Moreira Salles, in São Paulo, from March to July. They provide haunting depictions of the aftermath of a military coup, when quotidian life is assaulted by a new regime that has claimed for itself a right to extrajudicial violence. I recently met Teixeira at the institute’s offices in Rio de Janeiro, along with the organizers of the upcoming exhibition. Teixeira is burly, and spoke with a raspy drawl, partly a result of age and partly from a recent battle with COVID. He described his Santiago trip with a mix of gravity and mischievousness that seemed typical of not only his personality but his style.

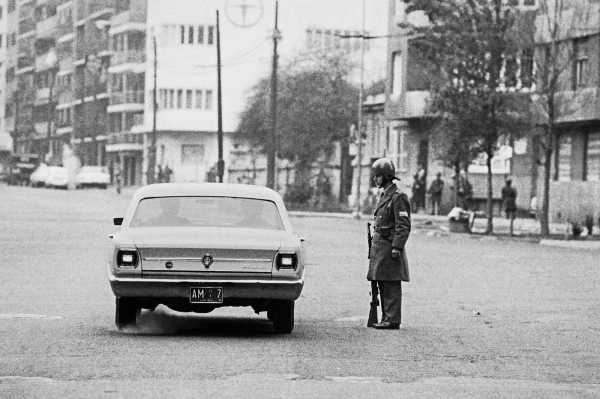

Teixeira’s pictures offer glimpses of both the brutality of illegitimate power and the fragility of it; he captures odd moments, when the absurdity of the regime’s claims—or the pathetic quality of its posturing—is laid bare. In one photo, detainees sit in the stands at the Estadio Nacional just below three soldiers keeping guard. One soldier is smiling, and the detainees look baffled and resigned; they stare out toward the field, not unlike soccer supporters watching a nil-nil draw. One senses that these men are accustomed to being jerked around by the state. In another photo, a car idles while an Army officer stands a few steps away from it. The officer’s clothes seem slightly too big, as though he were a child trying on his parent’s clothes. His posture is surprisingly unmenacing, as if he has no idea what to do.

The Army on the streets, Santiago, Chile, September 21-30, 1973.

These pictures evade the visual clichés of authoritarianism—masses hypnotized by the charismatic leader, for instance, or soldiers performing martial movements in synch. Such tropes echo the very sentiments a dictatorship aspires to instill, with their emphasis on fear and submission. Conversely, Teixeira’s images nudge the viewer to consider the inanity of those projecting power, and the humanity of those subject to it. Even his portrayals of mass protests are framed such that one can look closely at a wide array of faces. One of my favorites of the Santiago pictures shows a young guard in uniform standing half-heartedly in front of the rubble at La Moneda, machine gun in hand, guarding the building that the junta just sacked. It is a symbol of the paradox at the heart of tyrannies, with their claims to protect the very sense of order and stability that they destroy.

A guard in front of La Moneda, the Presidential palace, Santiago, Chile, September 21-30, 1973.

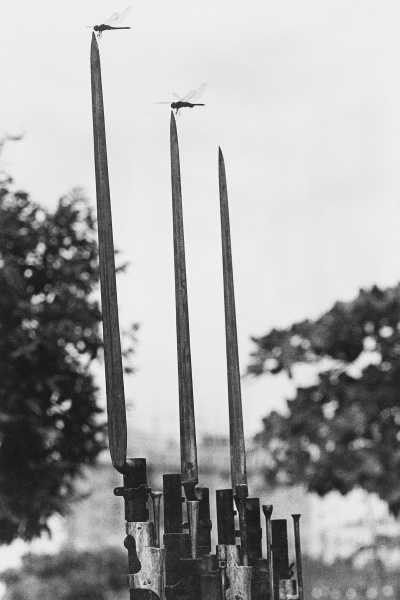

Bayonets and dragonflies during the hundred-year celebration of the Battle of Tuyutí, Aterro do Flamengo, Rio de Janeiro, May, 1966.

Political prisoners arrive at the Estadio Nacional, Santiago, Chile, September 22, 1973.

Teixeira was born in 1935, in Irajuba, a small town in the northeastern state of Bahia. He moved to Rio in his early twenties and started working at the newspaper Diário da Noite. In 1963, he was hired by the Jornal do Brasil, and worked there for the next forty-seven years, until the paper discontinued its print edition, in 2010. (It resumed the print edition in 2018.) In his second year at the paper, the military overthrew the government of leftist President João Goulart. A photograph that Teixeira took of the seizure of the Copacabana Fort, in April, 1964, hints at the ironic sensibility that he would develop throughout his career. We see a skinny soldier in the dark, during a torrential rainstorm, his silhouette framed by the blasted lights of what looks like a military jeep. The soldier’s posture is awkward, almost inattentive; the whole mood is one of melancholy, if not desolation. With its air of anticlimax, the picture brings to mind the protracted political process that led to the coup in the first place, its tragedy of errors.

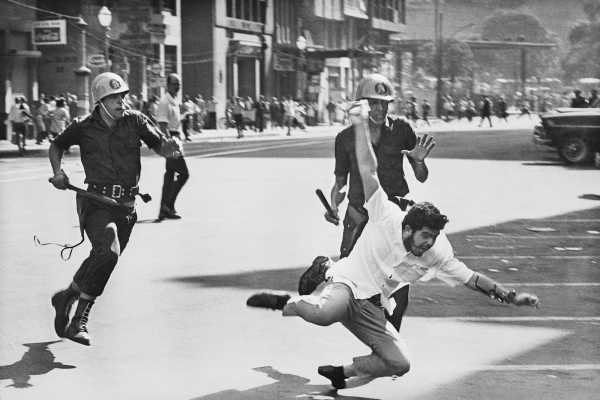

One of Teixeira’s most famous photos, “Caça ao estudante. Sexta-feira Sangrenta,” was taken four years later, during a violently repressed student protest in Rio that became known in the country as Bloody Friday. Two officers carrying truncheons run after a protester, who appears to fall, his glasses caught by the camera in midair. The certainty that the student is about to take a beating is offset, somewhat, by the ridiculous postures of the officers. They seem to be panting, running awkwardly, whereas the student, whose identity or fate could not be confirmed after the incident, appears vigorous, his movements nimble. The photo became an emblem of the regime’s violence. With hindsight, it also subtly underlines the military’s inability to tame the forces that would eventually overthrow it.

The hunt for the student during Bloody Friday (“Caça ao estudante. Sexta-Feira Sangrenta”), a protest against the Brazilian dictatorship which was heavily repressed by the regime, Rio de Janeiro, June 21, 1968.

At the Jornal do Brasil, Teixeira had to nurture his craft while remaining careful not to alarm government officials to the point that they prevented him from returning the following week to take pictures again. There were often censors at the Jornal do Brasil headquarters, checking on what the paper was publishing, and a more heavy-handed approach arguably could have landed him in trouble. His style, then, might have grown partly out of necessity. Still, some of his photographs mock alleged military might in a remarkably unabashed way, as in his image of a Brazilian Air Force officer falling from a motorcycle, a picture that now seems to foreshadow the far-right ex-President Jair Bolsonaro’s obsession with motorcades.

By the time he went to Chile, Teixeira had grown used to furtively taking the film out of his camera, and hiding his own political allegiances to avoid capture. One day in Santiago, a soldier caught him snapping a shot of a military truck unloading beef—Chile had been plagued with chronic food shortages—and took him to be interrogated by a colonel. When Teixeira was asked what he’d been doing, he cursed the “subversives,” and claimed that he worked for the “Condessa’s paper, a Catholic newspaper,” he told me. Condessa was the Countess Maurina Pereira Carneiro, a businesswoman and staunch Catholic who then owned the Jornal do Brasil. “I was always mentioning the Condessa,” Teixeira recalled, laughing. The paper, which became increasingly outspoken against the Brazilian government’s censorship, was not a Catholic paper. But the strategy worked that day. Even so, Teixeira was forced to spend the night away from his hotel. The colonel told him that he wasn’t detained, that they were just having coffee. “And so I stayed there having coffee for the whole night,” Teixeira said.

The March of the One Hundred Thousand (“Passeata dos Cem Mil”), in Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro, June 26, 1968.

A stain made by tear gas, Rio de Janeiro, June 21, 1968.

There were other close calls. During a visit to a cemetery, Teixeira glimpsed corpses of young people arriving and being deposited in a room, the blood on their bodies still apparently fresh. Trying to evade the attention of guards, he managed to reach the room, but was pistol-whipped when he was about to click.

Such tenacity led to one of the biggest scoops of his career, early in that Santiago trip. In one of his post-curfew chats at the Hotel Carrera bar, the wife of a military attaché gave him a tip. There had been rumors, since the coup, about the health of Pablo Neruda, the great Chilean poet, who had prostate cancer; Teixeira’s contact told him that Neruda was very ill and had just been transferred from his house in Isla Negra to the Santa María Clinic, in Santiago. On September 23rd, Teixeira went to the hospital, but was denied access to Neruda; that same night, the poet was pronounced dead. The following morning, Teixeira returned to the hospital, and, although a crowd had already gathered around the building, he managed to sneak in through a side door.

Inside the building, he found Matilde Urrutia, Neruda’s widow, by her husband’s corpse. While speaking with her, Teixeira dropped the name of the Brazilian novelist Jorge Amado, a friend of the couple who had been a Communist militant. Urrutia allowed Teixeira to stay and accompany her, first during the wake at La Chascona, the poet’s house in Santiago, and then throughout the funeral procession toward the city’s main cemetery. Teixeira’s first pictures that day show a desolate, narrow room, where Neruda lay in a cot, and later in a coffin, with his head wrapped in cloth. The procession grew spontaneously into an agglomeration, and then a kind of protest. The facial expressions in Teixeira’s photos are grave, but might betray a degree of apprehension, too—the military, after all, could intervene at any moment, which might have provoked a bloodbath. Participants chanted the “Internationale” and other leftist hymns as the poet was carried toward the cemetery. Teixeira still recalls the emotion of bearing witness to Neruda’s power as a cultural figure. “I was very moved but held the camera firmly in my hands and pressed it to my face,” he told me. “I had tears running in my eyes.”

The body of Pablo Neruda on its way to the General Cemetery of Santiago, Chile, September 25, 1973.

A crowd follows the arrival of Pablo Neruda’s body at the General Cemetery of Santiago, Chile, September 25, 1973.

A huge gathering at the burial of Pablo Neruda. Outside the cemetery, heavy contingents of the junta’s troops stood on alert.

Neruda was a former Presidential candidate and Communist senator, and a close friend to the ousted President Salvador Allende, who had died by suicide while the Presidential palace was under siege. He was also a potential target of the junta. Not long before, the new junta had murdered Víctor Jara, a popular leftist singer. Just this year, after decades of suspicion surrounding the circumstances of Neruda’s death—and ten years after the exhumation of his body—one of the poet’s nephews, Rodolfo Reyes, claimed that there is now conclusive evidence of foul play. According to Reyes, a new report, by a panel of international scientists, confirmed the presence of a toxin linked to botulism in bone and teeth samples, pointing to a likely assassination. The Chilean courts have not yet pronounced any decision based on the findings.

During the funeral procession, fifty years ago, Pinochet did not order an intervention. As Teixeira remembers it, the general called a press conference, probably to stall the event’s momentum. I asked him whether any journalists there that day thought the press conference was more newsworthy than the procession. “Of course, some people scattered,” he said. “But I wasn’t going to leave his body to go see that bastard Pinochet.”

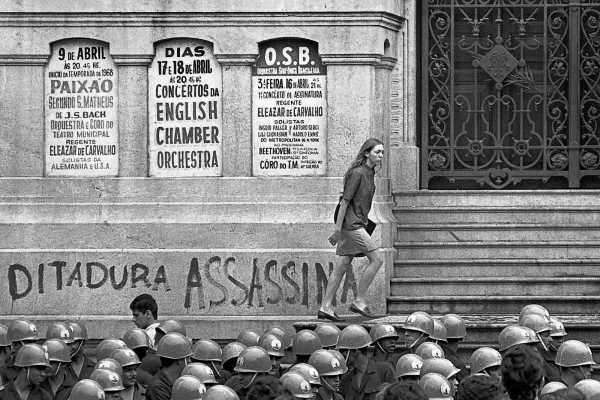

Student on the stairs of the Municipal Theatre, Rio de Janeiro, 1968.

Sourse: newyorker.com