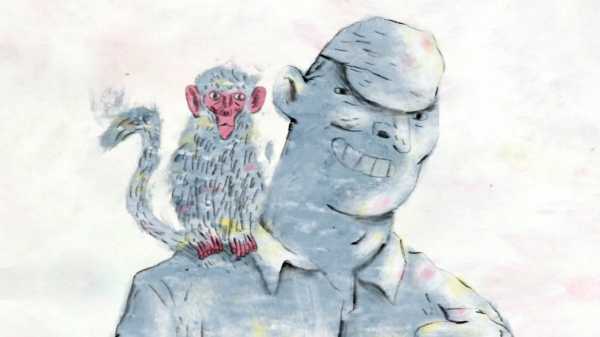

A family meal can have a certain magic. At the outset of Laura Gonçalves’s animated short “The Garbage Man,” a group of relatives gather around a table, and the conversation drifts—naturally, inevitably—to Manuel Botão, the filmmaker’s late uncle. Botão watches over the festivities from a photograph on the wall, sporting a cheeky smile and a monkey on his shoulder. As each narrator in turn picks up the thread of his life and passes it along as seamlessly as they pass the wine, Botão expands beyond the confines of his picture frame, and another portrait of him emerges—part MacGyver, part mischievous Santa Claus—from the composite of their recollections.

Though the style of the film is magical and imaginative, the details about Botão’s past—his conscription in the Portuguese Colonial War, his family’s flight across the border during the dictatorship, and his thirty years as a sanitation worker in Paris—are true to life. The audio in the film is drawn from interviews that Gonçalves conducted with her family members, which she then stitched together to create the narrative. Since her uncle’s death, more than a decade ago, Gonçalves has become fascinated with her family’s love of reciting the same well-worn stories over and over. “It’s kind of automatic. You all use the same words,” Gonçalves told me. Even so, “people still laugh. It’s like they’re hearing it for the first time.” Sometimes the tales that came out in the making of “The Garbage Man” surprise and inform—Gonçalves had never known, for example, that her uncle brought pineapples home from the war in Angola—but they are primarily incantations, keeping Botão alive, tapping into a readily available reservoir of joy.

As time passes and stories pile up, it can become difficult to distinguish between original memories and those borrowed from family lore or photographs, “those memories that are not really yours,” as Gonçalves put it. The animation in “The Garbage Man” revels in this ambiguity, bringing together the past and the present, the real and the imagined, and sitting them all down over lunch. While the present is rendered in monochromatic pencil, the more surreal elements of the film are awash in dreamy blues, pinks, and yellows. “I wanted to go really far away into the past, while never leaving the table,” Gonçalves said. “So we are here, but we are also in a house on a farm more than fifty years ago.” All the while, the line drawings shift and flicker, contingent as memory itself.

By the time Gonçalves started conceptualizing the film, in 2019, she could no longer clearly picture her uncle’s face. Drawing him from photographs felt disingenuous, so she cropped his head out of the frame for most of the film, hoping that the resulting anonymity would allow viewers to more easily see their own lives reflected in the narrative. “This is, of course, a personal story,” she said. But, she added, “the more abstract you let these things be, the more people can feel represented.” When Botão steps out of his portrait into the room, a giant brought to life by his relatives’ stories, his mythic proportions ring true for anyone who has conjured a loved one by memory.

Sourse: newyorker.com