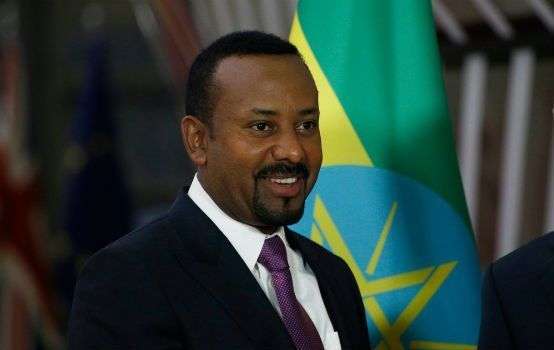

ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA – Legendary Indian peace activist Mahatma Gandhi was nominated five times for the Nobel Peace Prize but never won. Yet Ethiopia’s dynamic 43-year-old prime minister just got it on his first shot, after beating 300 other candidates.

Awarded since 1901 for outstanding contributions to peace, this year’s prize recognized Abiy Ahmed’s “efforts to achieve peace and international cooperation, and in particular his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea.”

The Nobel committee noted Abiy’s other accomplishments, including his lifting of the country’s state of emergency, the release of thousands of political prisoners, the relaxing of media censorship, the legalization of outlawed opposition groups, his tackling corruption, and the promotion of women in politics.

The Addis Ababa locals I chatted with after the October 11 announcement seemed to concur, saying Abiy deserved it, and that they were happy for him and what the award means for Ethiopia.

Advertisement

But you can never be too sure with Ethiopians. They keep their cards so close to their chests as to make my people, the recalcitrant British, look positively flamboyant. Yet certainly on Twitter, where the mask tends to come off all too easily, many posts from Ethiopians—both at home and abroad—were critical of the committee’s choice.

“The mystical Ethio-Eritrean deal continues to win awards and make headlines without actually making any differences on the ground,” tweeted Selan Kidane. “I think it should become the 9th wonder of the world.”

She has a point. Despite the jubilant scenes that greeted Ethiopia’s apparent resolution with Eritrea last year—with the border opening for the first time in 20 years—it’s become clear that Abiy has not delivered what was initially hoped for.

Today, the land border is once again closed, both governments having returned to the status quo. There are few signs that the much-heralded peace agreement has affected any meaningful long-term change on either side of the border.

To obtain what I thought might prove a more candid local opinion, I met with an old acquaintance, a Ph.D. student, and a professor friend of his, both in their thirties, from Addis Ababa University.

“I thought my country was worth something, but to be sold for $900,000, I had no idea it was so cheap,” said my friend, alluding to the Nobel prize money Abiy won. The peace deal with Eritrea was assisted by the likes of Saudi Arabia and the U.S., while the Ethiopian people still don’t know the actual terms of the final agreement, as it has not been made public.

“I was totally shocked. I couldn’t believe the committee would stoop so low,” said the professor. “In my lifetime, I have never known so many people to die in Ethiopia as this year. It’s the worst time for Ethiopia. It is more fragile than ever.”

Over fantastic macchiatos that are the benchmark for Addis Ababa’s café scene and that can, for a caffeine-buzzing moment, help transcend Ethiopia’s woes, both expanded on how the award further confirms their suspicions of foreigners trying to understand Ethiopia. It’s a cynicism with which I have some sympathy. Even the Nobel committee acknowledged that Abiy’s win comes at a time when Ethiopia is in the midst of extreme tumult, with myriad threats to the country’s peace and security.

“Many challenges remain unresolved,” noted the committee in its statement. “Ethnic strife continues to escalate, and we have seen troubling examples of this in recent weeks and months. No doubt some people will think this year’s prize is being awarded too early.”

Indeed, much of the jubilation that met Abiy’s rapid-fire reforms in 2018 has been replaced by concerns over his repressive measures to contain dissent.

This was put into stark relief the weekend after he was awarded the prize, when Addis Ababa was abuzz over whether there would be a protest on Sunday in Meskel Square, a large open area at the heart of the city. The authorities declared that the rally wasn’t permitted and a clampdown ensued. Traffic was held up at checkpoints across the city and along major roads to the capital. There were reports of arbitrary arrests.

The divisiveness of Abiy’s award is not without precedent. The Nobel committee has a history of making questionable choices. In 1973, the award was given to Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho, even though earlier that year, Kissinger had spearheaded America’s secret bombing campaign in Cambodia, which killed hundreds of thousands of people. In 1991, it went to Aung San Suu Kyi, arguably justified at the time given her non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights in Burma, though since then she has refused to speak out against the mass violence committed by the military against the Rohingya. In 1994, the prize went to Yasser Arafat, Shimon Peres, and Yitzakh Rabin, though the Oslo Accords proved just another temporary stopgap in what remains one of the world’s most intractable conflicts. In 2009, the award was given to President Barack Obama “for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples,” even though he was only nine months into his tenure—even he said he was surprised by and undeserving of it. And in 2012, the award went to the European Union for “over six decades contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights” (isn’t that what they should be doing anyhow?). There are other examples.

The committee’s choice of Abiy testifies to how well this energetic and charismatic 43-year-old has gone over on the international stage. But his brash style has fueled accusations, certainly in Ethiopia, that he is more concerned with burnishing a personality cult than focusing on the gritty necessities of his job.

The day before the award announcement, Abiy hosted the inauguration of Unity Park, a $170 million renovation of a section of the Imperial Palace compound that Abiy has opened to the public for the first time.

The unveiling of this once secretive place where former rulers plotted purges and tortured prisoners is meant to show that the government is moving away from authoritarianism and towards democratic values.

But some have labeled this a massive vanity project, arguing the money would have been better spent elsewhere in a country struggling with poverty and shoddy infrastructure.

“People are getting frustrated that he is a showman,” says Dessalegn Channie, chairman of the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA) opposition party. “He focuses on acts that have a public relationship impact.”

Ethiopia has a history of leaders who do well on the international stage while hiding the reality back home. Few modern rulers have become so deeply associated with a country’s image as Emperor Haile Selassie did when he governed Ethiopia from 1941 to 1974. But despite his elegant performance on the world stage, he did very little to develop his country. The Ethiopia at the end of his reign was little less feudal than it had been in the 1930s.

Meles Zenawi, prime minister from 1991 to 2012, dazzled world leaders with his hefty political intellect and oratory skills, and remains beloved by many Ethiopians. But beneath his velvet glove was an iron fist: no dissent was permitted, political opponents were imprisoned or fled into exile, elections results were highly dubious, those who protested afterwards were met with crackdowns, and anti-terrorism laws were used to stifle opposition and gag journalists.

Abiy, admittedly, and thankfully, appears cut from a very different cloth. Even his critics tend to acknowledge that on the whole he seems a pretty decent bloke whose heart is in the right place. (Though I wonder if he also harbors some of the intellectual elitism that openly permeates the higher echelons of Ethiopian society and that condemns the ordinary Ethiopian for being so poor and dumb as to need to be led around by the nose.)

Abiy now finds himself in a position similar to Barack Obama’s. Many argue that Obama failed to live up to his award, especially given his foreign policy stances on the likes of Syria. Abiy, at least, still has a chance to deliver on his promise, though overcoming the challenges Ethiopia faces both beyond its borders and internally will require enormous political acumen, willpower, and stamina.

The Nobel committee says it “believes it is now that Abiy Ahmed’s efforts deserve recognition and need encouragement,” and that it “hopes that the Nobel Peace Prize will strengthen Prime Minister Abiy in his important work for peace and reconciliation.”

A commendable sentiment, perhaps—Abiy needs all the encouragement he can get, given the febrile and labyrinthine landscape of Ethiopian politics. But at the same time, awarding the prize before any tangible success has been achieved only piles further pressure on Abiy when he already must overcome myriad challenges and opponents to succeed.

So whether the award is justified, good luck to him, I say—for the sake of more than 100 million Ethiopians struggling to get by.

James Jeffrey is a freelance journalist who splits his time between the Horn of Africa, the U.S., and the UK, and writes for various international media. Follow him on Twitter @jrfjeffrey.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com