Research into the backgrounds of members of the Integrity Initiative’s Spanish ‘cluster’ has led to some extremely troubling conclusions.

On December 19 2017, the House of Commons’ Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee convened its ‘fake news’ inquiry’s first oral evidence session, hearing testimony from a number of witnesses.

Among them were David Alandete, Editor of El Pais, Francisco de Borja Lasheras, Director of the European Council on Foreign Relation’s Madrid Office, and Mira Milosevich-Juaristi, Senior Fellow for Russia and Euroasia at Elcano Institute.They’d been invited to discuss an alleged Kremlin effort to interfere in the October 2017 Catalan independence referendum via a dastardly nexus of social media, bots, trolls, Sputnik News and RT — and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange.

What the trio failed to disclose, and are yet to acknowledge publicly almost a year later, is they are both directly and indirectly connected to the Integrity Initiative — an “information war effort” based in London that has received millions in UK government funds and is subject to more than one official investigation into its activities.

Even more troublingly however, their testimony — which may have contributed significantly to Ecuador’s March 2018 decision to cut off Assange’s access to the internet, and bar him from receiving any visitors other than his legal team — has been condemned as “exceptionally misleading” an independent data analyst, who also submitted expert testimony to the Committee.

Birds of a Cluster

The shadowy organization maintains ‘clusters’ — secret networks of politicians, businesspeople, military officials, academics and journalists — the world over who “understand the threat posed to Western nations” by Russian “disinformation” and can be mobilized to influence domestic politics.

The files suggest clusters are operational in France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Norway, Serbia, Spain and the UK — and there are plans to extend the scheme to every corner of the globe.

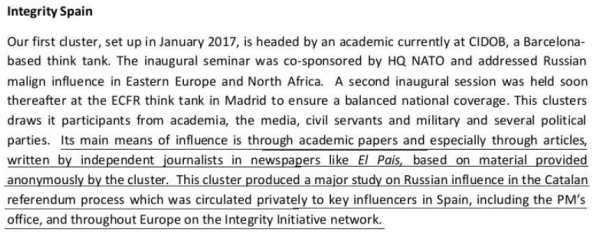

Lasheras and Milosevich-Juaristi are both members of Integrity Initiative’s Spanish cluster, which according to internal files “draws its participants from academia, the media, civil servants, military and several political parties”.

Integrity Initiative on its Spanish Cluster © Integrity Initiative

It’s unknown whether the “major study” referred to one of the pieces of evidence provided by the Committee — but false information was apparently provided to its inquiry by Alandete, Lasheras and Milosevich-Juaristi, and may have informed the incendiary language of its interim report published in July.

“We heard evidence that showed alleged Russian interference in the Spanish Referendum, in October 2017. During the Referendum campaign, Russia provoked conflict, through a mixture of misleading information and disinformation, between people within Spain, and between Spain and other member states in the EU, and in NATO,” the committee wrote.

Setting the Stage

On October 1 2017, the autonomous region of Catalonia convened a referendum on the question of its independence.

In the weeks prior, Assange had tweeted extensively about the impending plebiscite, strongly supporting Catalan separatists’ aspirations of self-determination. His social media activity in this regard would increase significantly when the Spanish government declared the vote illegal, leading to violent protests and arrests of Catalan politicians and activists, as well as the seizure of ballots and raids on polling stations by authorities.

His postings on the subject would be retweeted thousands of times by his supporters — and supporters of Catalan independence — and found their way into a number of Sputnik News and RT reports on the topic.

As a full-blown crisis was beginning to erupt, former Spanish Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez reportedly asked Grupo PRISA — Spain’s most powerful media conglomerate and owner of El Pais — to issue a “firm response” to the Catalonian independence movement.

Mere days later, El Pais duly began publishing stories alleging Assange — and Edward Snowden, who likewise supported the separatists — helping Sputnik News and RT to promulgate “fake news” about events in Catalonia. These baseless allegations were echoed in reports issued by a number of organizations with established histories of disseminating anti-Kremlin disinformation, including the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab, and NATO’s StratCom, and eventually proliferated to such a degree the dubious notion that online support for Catalan independence was effectively a Russian plot, facilitated — if not led — by Assange became widespread in mainstream Western discourse.

It was El Pais’ pivotal initial role in perpetuating this notion that led to Editor Alandete’s invitation to the December 19 Committee session — and he brought with him the two individuals who’d provided much of the data his paper’s journalists cited supporting their theory of Russian interference in the referendum.

Lasheras and Milosevich-Juarist both presented extensive data they said informed their conclusions of Kremlin meddling to the parliamentary panel — but in a telling concession, Milosevich-Juaristi admitted under questioning by Ian C. Lucas MP he “[had] no evidence” the Russian government sought to achieve “any concrete result” in the referendum campaign. Lasheras echoed his associate’s sentiments, saying “we have no specific evidence”, and “we do not know”.

‘Exceptionally Misleading’

Issues with the trio’s ‘expert’ testimony don’t end there. In written evidence submitted to the inquiry by M C McGrath — founding director of Transparency Toolkit, a non-profit organization helping journalists and human rights groups collect, analyze, and understand data online — raises serious questions about their competence and probity.

“I discovered numerous instances of misinterpretation of data sources, use of inaccurate information, lack of attention to detail, and poor research methodology. As a result of these errors, I would suggest that the conclusions drawn in these reports and presented in the December 19 Committee session are exceptionally misleading,” she wrote.

Specifically, her review identified; a failure to accurately use digital analytics tools; dubious research methodology; one-sided analysis ignoring botnets disseminating anti-Catalan independence messages; exaggeration of the influence of bots and trolls; careless analysis of data from questionable sources; overstatement of the influence of Assange on RT and Sputnik.”Reports such as El Pais’identify a suspiciously large number of tweets about Catalonia from Russian bots and trolls. There is nothing is unusual about the proportion of accounts located in Russia that retweeted Julian Assange’s Catalonia-related tweets. A sample of 23,418 retweets of Assange’s tweets discussing Catalonia in September and October 2017 shows 2.1 percent in Russia, in line with world population ratios…[it does] not show disproportionate interest in the situation in Catalonia from Russia. In fact, Julian Assange’s retweeters appear to be concentrated in the US,” she observed.

Even more damningly, McGrath found Sputnik and RT only mentioned Assange in a small minority of their stories about Catalonia. Using Media Cloud, a tool created by researchers at MIT and Harvard for tracking the spread of news stories and ideas, she analyzed the two outlets’ coverage of the situation in Catalonia between September 1 and December 8 2017, during which the pair published 596 stories about Catalonia.”In these stories, 2,998 sentences mention Catalonia specifically. Only 17 of these 596 stories about Catalonia, or 2.85 percent, also mention Assange. Furthermore, analysis of sentences mentioning Assange shows references were centered around a few isolated events and comments. A sample of 53,929 retweets of 1,508 Catalonia-related tweets posted in September and October 2017 by RT and Sputnik’s English and Spanish Twitter accounts shows only 22 of the 1508 tweets (1.46 percent) mention Assange at all….2.86 percent of retweets of tweets from RT and Sputnik about Catalonia mention Assange,”she concluded.

Birds of a Cluster

It’s uncertain whether the trio deliberately misled the committee, but misled the panel certainly were — and these falsehoods could have seismic real-world consequences.

For instance, the committee’s apparent endorsement of the trio’s contention that an individual or group being quoted by Sputnik and/or RT is evidence they are assisting in — if not leading — a Russian disinformation campaign, hands potentially significant ammunition to anyone wishing to discredit or delegitimize critical voices in mainstream discourse.

More sinisterly though, if the recommendations contained in the committee’s interim report are heeded by the government, legislation could severely restrict if not outright stifle the capabilities of alternative information sources and hamper the publication of work by independent researchers and journalists.

If laws do materialise, they will at least in-part be inspired by unsound analysis that, whether consciously or unconsciously, is not based on facts or evidence — and an organization which claims to “defend democracy from disinformation” could arguably be culpable.

Committee Chair Damian Lewis has been asked for comment by Sputnik, but as of December 14 is yet to respond.

Sourse: sputniknews.com