This story is part of a group of stories called

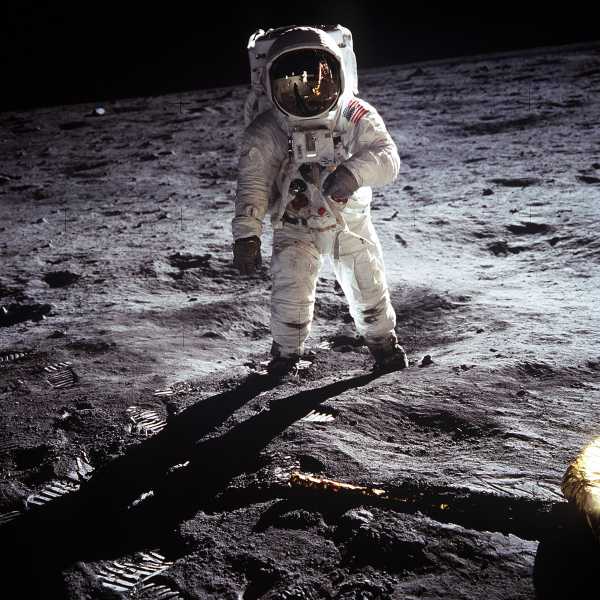

The holy grail for collectors of space memorabilia is anything that was flown to the moon during the six Apollo missions and unloaded onto the celestial crust. It would be junk in any other context; vintage scientific equipment lucky enough to be projected at escape velocity to a barren destination 234,000 miles away. What makes those spare parts invaluable, explains Robert Pearlman, editor of the space-hobbyist consumer guide CollectSPACE (and an avid lunar antiquary himself), is when they’ve been stained by lunar dust — physical proof of a journey that still seems impossible.

”As you can imagine, the number of those items that are in private hands is very, very small,” he continues. “So part of the reason they’re valuable is simple supply-and-demand economics. But the other reason is that they represent the pinnacle of human achievement.”

“They represent the pinnacle of human achievement”

Pearlman says the items slowly decrease in desirability from there. Just below the relics caked with moon dust are those that landed on the surface but were left inside the lunar module; a staircase away from a massive spike in secondhand value. After that are items that were isolated in lunar orbit, with astronauts like Michael Collins and Richard Gordon, who managed the command module while they waited for the away team to conclude their business a few hundred meters below.

Then you enter the Wild West of merchandise that remained on Earth — various appendages of the Apollo program, and its lesser-known progenitors Project Mercury and Project Gemini. (The value basement, says Pearlman, are the items mined out of the latter-day Skylab and Space Shuttle ventures throughout the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Space collectors, like most Americans, prefer to remember NASA when it was at its apex.)

But memorabilia from the Apollo 11 mission reigns supreme. The maiden voyage to the moon is the one most fixed in the American storybook, so it is no surprise that the trickle of mementos from that flight demand a higher price than anything that’s come before or since.

July 20th marks Apollo 11’s 50th anniversary, and Sotheby’s is celebrating on that day with a specialized auction full of material from the space program. The marquee item? Three bundles of magnetic videotape, filmed at Mission Control in Houston, Texas, which represent the “earliest, sharpest, and most accurate” documentation of the broadcasts beamed out by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as they took their first steps on the moon. The estimated market value is between $1 million and $2 million, but the original owner was a NASA intern, who bought the tapes at a government surplus auction for $217.77 in 1976. Cassandra Hatton, a senior specialist at Sotheby’s who focuses on science history, explains that the field is new enough, and volatile enough, that prices are able to jump 10,000 percent in about 40 years. This is unusual.

”Sotheby’s has been around since 1744. The first auction we had was a book auction. We had that many years of auction records on the books. We had that much data on the value. If somebody came to me and said, ‘What do you think this book is worth?’ It’s so easy for me to give someone an answer,” Hatton says. “For the space material, it’s so much more difficult. The stuff was created so recently, there’s so few auction records, there’s a wide variety in the different houses that have sold this material. It’s a very steep learning curve. Coming up with those values takes a tremendous amount of research, both in pricing and history, just to know what these items are.”

Who owns the moon?

Space hobbyists have been around for the length of the space race, but Pearlman explains that the first formal high-society space auctions were hosted in Beverly Hills in the early ’90s by a (now-defunct) house called Superior Galleries. It was a biannual event, drawing interest from all over the country, and it gathered its merchandise by either cosigning items directly from other collectors or asking former astronauts to put their personal effects on sale. The market tends to spike whenever people are talking about space again: 1995, after the release of Apollo 13; 1999, during the 30th anniversary of Apollo 11, and so on. By 2010, major auction companies like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams were organizing their own space galas, each focused on a period of 15 years between the mid-’60s and ’70s — Earth’s brief love affair with the moon.

It’s odd to consider how private collectors could spend massive amounts of money in order to claim ownership over one of the most famous public projects in American history. After all, taxpayers paid to get that equipment to the moon in the first place. Shouldn’t all that merchandise have been awarded to the Library of Congress minutes after splashdown? Pearlman tells me he hears that question a lot. The reality, he says, is that NASA, like any other governmental organization, has a surplus.

In the ’70s, the administration reached an agreement with the Smithsonian, effectively giving the museum the first right of refusal on all the major artifacts that NASA no longer needs. That means that Apollo’s big-ticket items — the garments that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin wore on the lunar surface, the specimens they brought back home — are in government hands, and are available for display at museums across the country.

The remainder, says Pearlman, were the “nuts and bolts” of the space program — knickknacks that carry plenty of historical relevance but don’t make nearly as much sense behind a glass pane on a museum floor. (A good example is an Apollo 11 flight manual, which is expected to fetch around $9 million at a Christie’s auction this week.) A shocking number of those artifacts were plucked out of the government surplus system, just like the multimillion-dollar videotape on sale at Sotheby’s.

”Collectors recognized what that surplus material [actually] was. Sometimes after it had already reached the garbage dump,” says Pearlman. “It was saved, it was salvaged for years to come.”

The other legal way Apollo material hits consumer channels is via the men who lived it. NASA outfitted astronauts with what’s called a personal preference kit, or PPK — a small bag to stow keepsakes during their missions. After they retired and returned to Earth, that material was donated, or handed down to their kids, or, as the space auction market started percolating, sold at an enormous profit margin.

These sales, in particular, did not sit well with NASA. The agency could never squabble with the material purchased legally out of surplus stores, but it did file grievance with what it saw as former employees flipping government property to make a buck. Take the case of astronaut Edgar Mitchell, who brought a camera he kept from the Apollo 14 campaign to Bonhams in 2011. The government said it had no record of transferring that camera to Mitchell’s private estate, so after a legal entanglement, Mitchell was forced to sacrifice his keepsake back to his former boss.

NASA did file grievance with what it saw as former employees flipping government property to make a buck

Naturally, “United States v. Former Astronaut Edgar Mitchell” looks pretty ugly to the average American. Mitchell had kept that camera for 40 years before attempting to cash out, and the pettiness on the municipal side looked a lot like NASA eating its own young. That controversy forced the Obama administration into action; in 2012, the president signed a bill into law guaranteeing the “full ownership rights” of most anything the crew members of the Apollo, Mercury, and Gemini missions still had in their possession — records or not. Hatton says she was thankful for the legislation, because it purged a lot of the guesswork out of space appraisal.

“The legislation specifically says not moon rocks, not spacesuits, but any other expendable items they might have kept. Checklists, and other types of hardware, that’s theirs. They’re allowed to sell it,” she says. “It’s so helpful, because I don’t have to make some sort of judgment call. ‘This flew on a mission. Okay! Did it come from an astronaut? No? Then how did you get it? You didn’t obtain this in a legal way.”

The relationship between officials and private collectors has improved — but there’s still tension

Hatton says the relationship between the Smithsonian and her clients is, for the most part, positive. There are some private collectors who think they could do a better job of preserving space material than the museum system, but that is a constant across every moneyed enthusiast community.

Teasel Muir-Harmony, the Smithsonian NASA curator, reports the same buoyancy. “A lot of private collectors get into private collecting because they’re passionate about the subject. There’s a lot of material out there, and we don’t have the capacity to house it all,” she says.

Still, a layer of tension remains when you’re bartering national treasures. The most recent, and perhaps most famous, example surfaced in 2016. A woman named Nancy Carlson bought a yellowed bag that made it to the surface of the moon during Apollo 11. It was labeled “Lunar Sample Return,” and it was previously stuffed with moon rocks that the crew scrounged up during the two hours they spent walking around the landing site.

The specifics of Carlson’s purchase are laughable; she took it home for $995 at an auction in Texas hosted by the US Marshals Service, who were selling off the forfeited artifacts of Max Ary — who was convicted for the theft and reselling of space-related items in 2006. The bag itself was worth a king’s ransom; flown to outer space on Apollo 11, handled by Neil Armstrong himself, and — yes — stained with moon dust.

NASA didn’t even know the bag existed before Carlson sent it off to the administration to verify its lunar residue. The agency confirmed her suspicions, and also said that it wouldn’t be returned to her. NASA’s story is that it misidentified the bag as something far more innocuous before making it available to the public. Now it was out to correct that mistake. Carlson took the case to court, where a judge ruled that she had purchased the bag in good faith, and “in a sale conducted according to the law.” Carlson took the bag to auction in 2017 and walked away with $1.7 million.

It’s the sort of development that scares Michelle Hanlon, the co-founder of For All Moonkind, a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of the lunar expeditions. She says she doesn’t have anything against private collectors, but maintains the position that anything that returned home from Apollo 11 should be classified as a public artifact — treated with tenderness and exempt from commerce. “A lot of what we’re looking for is memorialization versus preservation,” she says. “What do we need to hold in our hand forever? What do we need to make sure we don’t forget that this happened?”

Hanlon analyzes space collecting with a very wide scope. The safety of the fragments that returned to Earth is important, sure, but she also wants to ensure that thousands of years from now, Neil Armstrong’s boot print remains stomped into the Sea of Tranquility. It makes you consider all the other plundered marvels of human history — the decline and fall of the Library of Alexandria; ISIL’s ongoing siege on heritage; the Parthenon of Athens, which has been smashed by mortars and pillaged by colonizers in the past 200 years, leaving you shaking your head as you walk back down the Acropolis. It’s bewildering to consider how quickly human innovation can become human history; how much faith we put into the idea that we are different and better now.

As Hatton says, space auctions are an extremely recent development, perfected by passionate men and women with a deep love for the space program. Perhaps this is the time to engage with those questions of preservation and value more seriously, as we decide that film of the first man on the moon should cost between $1 million and $2 million.

”We have the opportunity to do it right in space,” says Hanlon. “Because we haven’t gotten up there to ruin anything yet.”

Sign up for The Goods’ newsletter. Twice a week, we’ll send you the best Goods stories exploring what we buy, why we buy it, and why it matters.

Sourse: vox.com