After the NBP interest rate cut in May, the comments basically focus on just one issue: how much debtors will gain. And why is no one talking about how much savers will lose and how much higher inflation will cost us all?

“Interest rates finally down”. “How will the loan installment change”. “Lower interest rates will please borrowers”. Installments will drop by as much as several hundred złoty”. This is how the media reflects on the May decision of the Monetary Policy Council. The overwhelming majority of media content focuses only on how much debtors will gain and how happy they will be. This is how a machine for making people (at least some of them) happy on a mass scale was invented.

The only thing is that the interest rate was not invented to make debtors happy. The interest rate determines the price of money. That is, it determines how much you have to pay to borrow it and how much you can expect to pay to lend it (e.g. to a bank). In theory, central bank interest rates determine the so-called risk-free rate. But if someone actually wanted to borrow money on the market, they would have to pay an additional premium for individually assessed credit risk (i.e. the possibility that they will not return the money).

Advertisement See alsoProposal for you: 7% on a savings account for 5 months and an easy PLN 300 bonus for opening an account at Bank Pekao

Interest rate, or two sides of one coin

The interest rate is therefore the equilibrium price that determines the amount of savings and available sources of financing (that's the theory). The problem is that today this value is not set by the market, but by committees of state officials in central banks. They are not guided by the issue of market equilibrium, but by a whole range of different goals, the main one of which is usually maintaining a given level of inflation. In the case of central banks, the priority is to prevent deflation and the bankruptcy of large banks.

Read also

What is the actual inflation target of the National Bank of Poland? Because nobody believes in 2.5% anymore

Personally, I consider manual control of interest rates to be a harmful experiment and a dishonest element of central economic planning. But it is what it is and we must accept that such an important price in the economy is set by politically appointed state officials. And they recently decided out of the blue to lower interest rates at the NBP.

This arbitrary and POLITICAL decision (after all, we commonly talk about monetary policy) has very serious consequences for the entire economy. First, it divides costs and benefits between savers and debtors. What pleases the latter works to the detriment of the former. Why doesn't anyone calculate that each percentage point of interest rate decline translates into some PLN 21 billion in potential interest losses for households and businesses? It also reduces the interest costs of the banking sector by that much (or more).

On the other side of this balance sheet are borrowers who will pay lower interest on their debts. But not all of them. This only applies to entities indebted based on a variable interest rate . We are talking here mainly about two groups of debtors. The first are, of course, those indebted on housing loans, whose interest rate depends on the equation: WIBOR xM + margin (usually constant over time). They are the most talked about and they dominate the media headlines. The second group are enterprises, where the same interest rate model dominates in the case of corporate loans.

On the other hand, the change in NBP and interbank rates (i.e. WIBOR rates) will have no major impact on most consumer debtors. All installment or cash loans are often based on a fixed interest rate. Relatively, it is so high (e.g. 15%) that a change of 25-50 basis points has no significant impact on the amount of the monthly installment. This applies especially to the most expensive debt in the world, i.e. credit card debt.

It is worth adding that lower interest rates have two other consequences that are not often discussed. First, they increase the demand for credit and at the same time reduce the propensity to save. Simply put, when credit/loan is cheaper, people are more willing to take it out. This is how the law of supply and demand works. Second, when deposits pay next to nothing, why make them? Third, lower rates (and thus lower first loan installments) increase the creditworthiness of potential debtors and encourage them to take on larger liabilities. This is why bankers are unlikely to cry over the NBP interest rate cut.

Read also

MPC cuts interest rates. Tusk: Better late than never

And let's not forget that the largest debtor in the country is the State Treasury . When the Council lowers interest rates, the Minister of Finance pays less to service the monstrous public debt (which reached PLN 1.61 trillion at the end of 2024). The government can then allocate this money for other purposes. That is why politicians so widely demand the lowest interest rates. They also have another, more hidden goal in this.

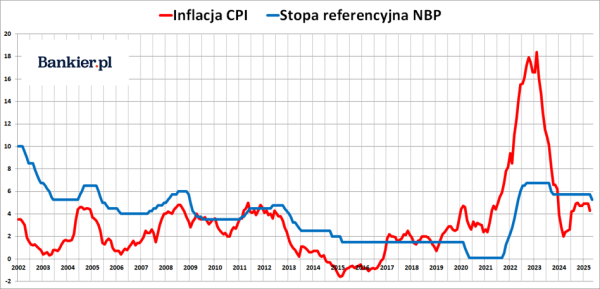

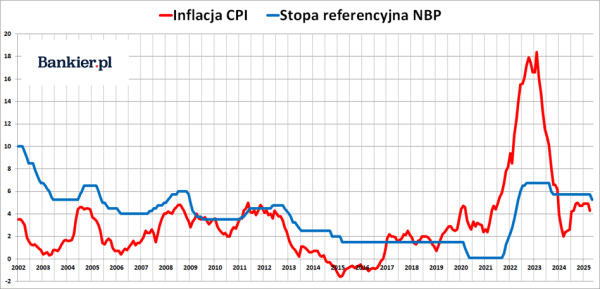

Lower rates mean higher inflation

They won't tell you that lower interest rates mean – ceteris paribus – higher inflation . That is, in conditions of lower interest rates, inflation will generally be higher than it would be in the scenario if rates were not cut. I would like to be understood here correctly: CPI inflation may fall anyway, regardless of the rate cut by the MPC (e.g. due to falling fuel prices, administrative freezing of energy prices or market disinflation processes). The point is that if the Council did not cut rates, then according to the NBP theory and models, in a year or two inflation would be lower than it actually will be.

– Interest rates lower by about 1 percentage point in a two-year horizon translate into inflation higher by about 0.7 percentage points two years later . This simple relationship does not depend on the specific level of market rates. An additional 0.7 percentage points means that in 2027 we are outside the upper band of deviations from the target. (…) In the light of the March and numerous previous projections, any reduction today is a departure from the mandate and harm to the Polish economy – said Joanna Tyrowicz in April, quoted by DGP.

So anyone who advocates lower interest rates is really asking for higher inflation. Of course, maintaining very high interest rates in an environment of low or even zero inflation would also be harmful, but that is not the dilemma we are currently facing (for example, the Swiss have such a “problem”, where CPI inflation has just fallen to zero, and with it also SNB interest rates).

And who is happy about higher inflation? First, debtors, because the decrease in the purchasing power of money reduces the real value of their obligations. Second, ruling politicians, because price increases drive nominal tax revenues (VAT, ZUS, PIT, etc.). Third, banks, because demand for their main product (i.e. loans) is growing. And third, those entities that will be the first to gain access to the money newly created by banks (e.g. development or construction companies, manufacturers of household appliances or cars – everything that is currently usually bought on credit).

However, the overwhelming majority of society loses out on inflation. First, because of the real loss of purchasing power of savings (even very small ones). Second, because of the increase in the cost of living. On a national scale, these are costs counted in tens of billions of zlotys. Let's make simple (not to say primitive) calculations. In 2023 (the latest available data), the average expenditure per person in Polish households amounted to PLN 1,636 per month. For a family of four, this amounts to about PLN 78,500 per year. The Central Statistical Office calculated that in 2024, CPI inflation averaged 3.6%. This means that, on average, just to maintain the current standard of living, such an average household had to spend PLN 2,827 more per year. This is the cost of inflation. It is different for everyone, depending on their expenditure structure, income level, balance sheet structure, etc. But it applies to everyone. To a greater or lesser extent.

Capitalists like low rates. Workers like low inflation.

The issue can also be approached in a more socialist way. Supporters of the “left sector” should note that the wealthy benefit the most from low interest rates, while the poor lose the most. It is the latter that is hit the hardest by inflation and it is they who have the hardest time making ends meet in conditions of faster growth in the cost of living. Although they usually do not have savings, they are not “owners” of housing loans either. Therefore, they do not benefit from the decrease in their interest rates. This privilege is reserved for representatives of the higher-earning part of society. The poor do not have creditworthiness and “will not get” a loan.

On the other hand, a reduction in interest rates usually leads to higher stock and bond prices. Therefore, the holders of financial assets – the wealthier part of society – benefit. Cheaper credit usually also leads to higher property prices. For leveraged fans of investing in concrete, this is a double bonus. And who cares if a young family has to pay n thousand more for their first apartment? They can take out a cheaper loan!

Read also

How Zero Interest Rates Are Making the Rich Richer

Therefore, a policy of low interest rates in the long run leads to subsidizing the rich at the expense of the poor. We saw this very well in the United States in 2009-21. In Poland, we are currently far from the ZIRP regime (zero interest rates), but the real rate (i.e. after taking into account inflation) after the upcoming reduction in credit costs may approach zero.

To sum up, the wealthier part of society has reasons to rejoice at lower interest rates: indebted property owners, investors, bankers, shareholders of development companies and politicians in power. The costs will be borne by everyone else, especially the poorest, who usually suffer the most from inflation and who do not care about the amount of the loan installment paid by their “landlord”.