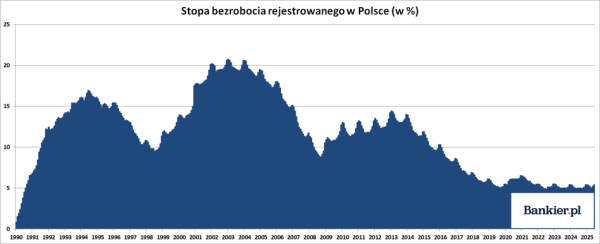

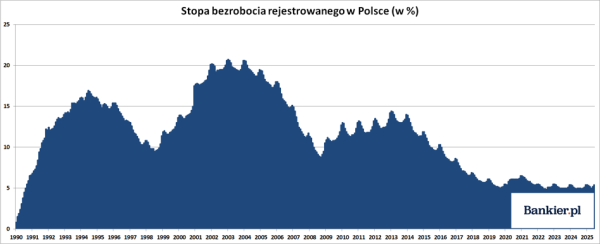

Defying seasonal patterns, both July and June saw increases in the registered unemployment rate. This statistic coincided with numerous reports of mass layoffs in Poland.

A surprise emerged in early July, when data from the Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy showed an increase in the unemployment rate in June from 5.0% to 5.1%. Economists surveyed by PAP Biznes expected unemployment to decline to 4.9% at the time, which would be consistent with seasonal patterns. It so happens that we observe a decline in the registered unemployment rate during the summer months. Due to the emergence of seasonal jobs in agriculture, construction, and tourism, official unemployment almost always declines in June, as well as in July and August.

Bankier.pl based on the Central Statistical Office

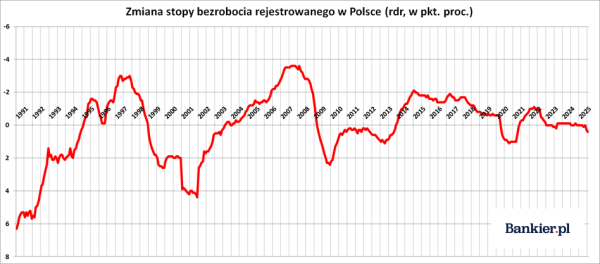

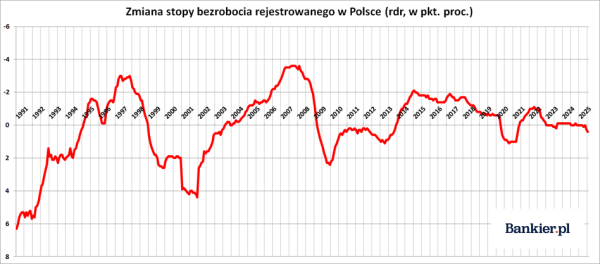

And although the registered unemployment rate remains low (i.e., close to the lowest levels in 35 years), its annual growth rate is already at its highest since the Covid shock of 2020-21. And if we ignore the economic consequences of the madness of government sanitary specialists, the last time we saw such a strong increase in the official unemployment rate was in 2013, during the deep economic slowdown accompanying the debt crisis in the eurozone.

Bankier.pl based on the Central Statistical Office

But the July statistics were an even bigger shock, showing an increase in the registered unemployment rate to 5.4%. Economists had expected a figure of 5.2%. The last time a monthly increase in unemployment occurred simultaneously in June and July was 24 years ago – in 2001, during the deep crisis on the Polish labor market. However, until recently, it was generally believed that the labor market was in good shape. So what happened to cause unemployment to rise?

Advertisement See also: Hungry for profit? We serve hot companies on a virtual plate. Dessert? Real prizes!

The first clue was the legislative changes introduced with the amendment to the Act on the Labor Market and Employment Services. This act entered into force on March 20, 2025, and generally facilitated obtaining unemployment status (desirable for many reasons, including, above all, access to healthcare services financed by the National Health Fund). For the first time, farmers (or at least those with farmer status) were allowed to register with labor offices. Secondly, registration was made possible at the place of residence, instead of at the registered address as was previously the case.

“July brought another surprise in the unemployment rate, which rose to 5.4%, compared to the expected 5.2%. The reason? Legislative changes continue to muddy the data. As a result, a total of over 50,000 additional unemployed people were registered in June and July! As a result, the unemployment rate will be significantly above 5.5% by the end of the year,” economists at Bank Pekao commented on the July data.

Is higher unemployment just a “statistical artifact”?

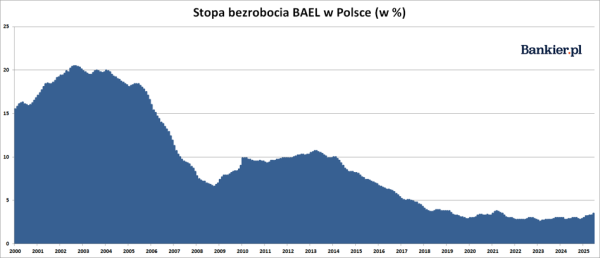

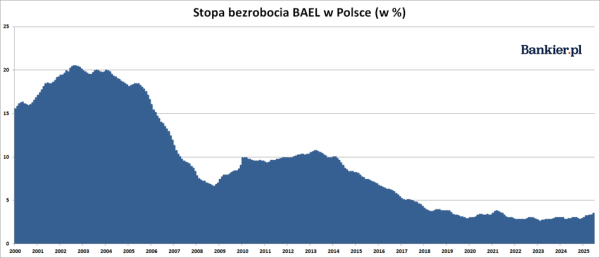

Typically, this type of explanation would close any further discussion. After all, every child knows that the number of registered unemployed in Poland is an administrative fiction and bears little resemblance to the number of people actually unable to find work. A simple look at the Labour Force Survey (LFS) reveals that the actual unemployment rate in Poland was recently around 3.0%, compared to around 5% in official data. This roughly two-percentage-point difference has persisted for years.

However, since the beginning of 2025, Eurostat data have also indicated an increase in the unemployment rate in Poland. The LFS unemployment rate rose from 2.9% in December to 3% in January, 3.2% in March, and finally 3.5% in June (statistics for July are not yet available). Theoretically, this indicator should be resistant to legislative changes because it uses a different (and stable over time) definition of the unemployed.

In the LFS (Labour Force Survey), an unemployed person is someone who is actively seeking work and is ready to start within two weeks. However, in labor office statistics, anyone registered as “unemployed” is considered “unemployed,” even if they work illegally or are not interested in taking up official employment at all. Hence the difference – approximately 300,000 false unemployed.

Bankier.pl based on the Central Statistical Office

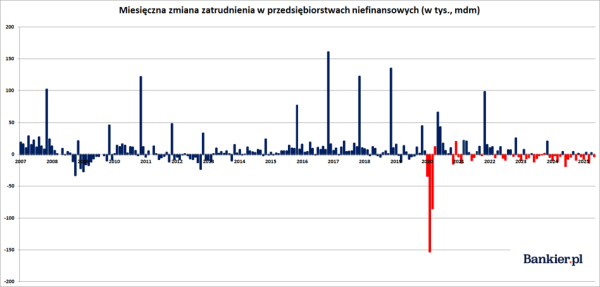

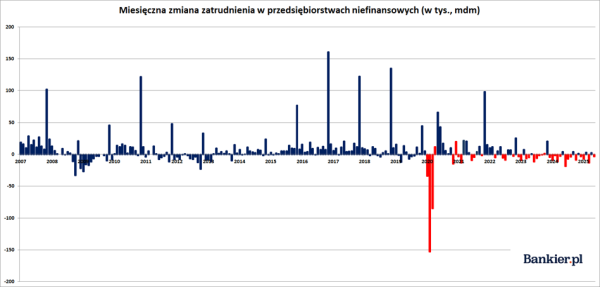

We have also been seeing disturbing trends in official employment statistics in the corporate sector (i.e., non-financial companies employing more than nine people) for some time now. Data for July 2025 indicated a deepening decline in employment. The number of full-time positions in large companies was 3,800 fewer than in June and 21,900 fewer than a year earlier. The trend is that employment in the corporate sector has been declining almost continuously since the beginning of 2023. For example, in 2023, the number of full-time positions decreased by 9,400, compared to 41,600 last year, and by a further 21,900 from January to July.

A wave of mass layoffs. Truth or myth?

All this is happening at a time when the media has been writing about a “wave of mass layoffs in Poland” for over a year now. Hardly a week goes by without news of mass layoffs at some company. Moreover, unlike in the 1990s, it's not state-owned enterprises that are laying off employees, but rather Polish branches of large foreign corporations. Examples? Greenbrier Poland in Oława will lay off 161 people. Fujitsu Technology Solutions plans to cut 834 positions. Aldi will shed nearly a hundred employees. Intel will lay off up to 24,000 people globally – some likely in Poland as well.

Each such case tells a slightly different story. Some of the layoffs stem from the global industrial recession that has been ongoing for the past three years, correcting the excesses of the lockdown boom of 2020-22 (when consumers were not allowed to consume many services, so they instead bought durable goods). Some are the result of the EU's insane climate policy, which has led to massive electricity price increases in the EU. Some are a consequence of wage increases in Poland and the shift of production to cheaper countries (and outside the EU). In still others, they are the result of technological changes (e.g., AI replacing programmers) or the years-long restructuring of ailing businesses.

All this information is compounded by anecdotal reports that even young people graduating from renowned universities are finding it increasingly difficult to find a job. It's no longer about a good job, but any job. Even employers are increasingly reluctant to lament the supposed “lack of workers.” Just a few years ago, such complaints were commonplace (headlines like: “x thousand drivers/construction workers/laborers are missing”).

At the same time , the statistics do not yet show the impact of the announced collective layoffs on the number of unemployed people dismissed for work-related reasons . In May, there were 36,600 such people. This is the same as in April and only 4,400 (or 12.7%) more than a year ago. Since the beginning of 2025, 36,000-37,000 people have been registered with labor offices each month. These numbers are not much different from what we saw in 2022-2024 and significantly lower than, for example, a decade ago (when the number was over 100,000).

Central Statistical Office

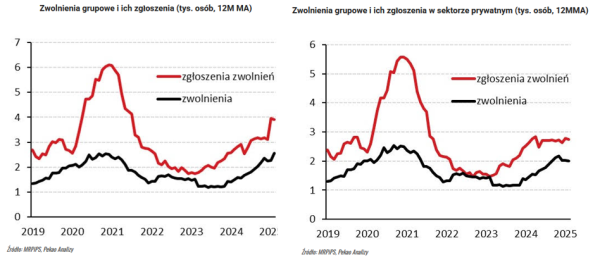

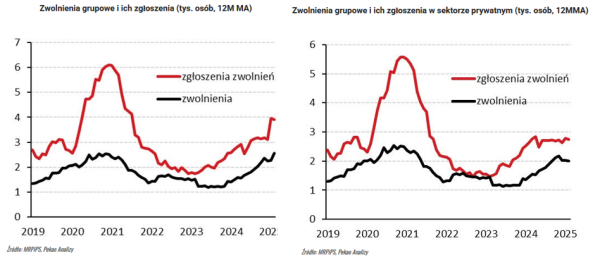

At the same time, government data shows that the number of reported collective layoffs increased significantly at the beginning of 2025, reaching the highest level since the economic crisis triggered by the 2020-21 lockdowns. However, if we exclude collective layoffs carried out as part of the restructuring of Poczta Polska, the number of reported layoffs in the private sector itself remained at a similar level to last year, according to a study by Pekao economists.

Pekao

This year's increase in the unemployment rate is also being downplayed by economists at PKO BP. “The atypical increase in the unemployment rate in recent months (inconsistent with the seasonal pattern, which would indicate its stabilization or decline) is related to, among other things, regulatory factors and the reform of the functioning of labor offices,” they wrote in the Economic Journal.

Economists from Poland's largest bank argue that the LFS data for Q2 indicated a decline in the unemployment rate (to 2.8% from 3.4% in Q1), accompanied by an increase in the number of employed persons. “The LFS data for 2Q25 suggest that the surprising increase in the unemployment rate at the beginning of the year was more noise than a real signal heralding a significant deterioration in the labor market. We also consider the increase in registered unemployment in July and June (the result of the labor office reform) to be noise,” they wrote.

What does all this mean? First, it's possible that mass layoff workers quickly find employment at other companies. In that case, we have nothing to worry about. The second possibility is that they can't find new work quickly but don't register (or haven't registered yet) with employment offices.

But there's also option number three, and it's called demography. Poland has been experiencing a decline in its working-age population for the past 10 years. Up to a point, this factor was mitigated by increased labor force participation (meaning more and more working-age people were working), but for several years now, the number of working Poles has been practically stagnant.

Meanwhile, the number of immigrants from other countries working in Poland is growing. In the first half of 2025, the total number of work permits issued to foreigners reached 823,000. Although this was 11% lower than the previous year, the share of foreigners among employees registered with the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS) increased from 7.3% to 7.6%. And these are no longer just Ukrainians and Belarusians, but increasingly also Colombians, Georgians, and Indians. And these are unlikely to register with the “intermediary” if laid off. In turn, some laid-off workers may be already of retirement age and will instead report to the ZUS (Social Insurance Institution).

In summary, over the past 10 years, the Polish labor market has undergone a profound transformation, and not all indicators are performing as they once did. The economic downturn from an employee's perspective is a fact, but the scale of this decline is currently difficult to assess. Finally, for demographic reasons, there is no return to the times of mass and long-term unemployment we remember from the early 21st century or from 2010-2015.