Few filmmakers possess the ability to stir controversy like Quentin Tarantino, whose career has been marked by it at almost every turn.

Whether he’s publicly arguing with Spike Lee over Tarantino’s use of a racial slur to refer to black people in many of his scripts, drawing criticism and boycotts from police organizations for supporting groups that fight police brutality, or seeing past mistreatment of his performers come to light, Tarantino makes headlines almost as much for the things he does as for the movies he creates.

This characteristic has led to a general sense that the director is “problematic” (imagine several dozen more air quotes around that) from people who don’t quite follow the endless back-and-forth of Film Twitter, without a full sense of why. And the conversation has reached a fever pitch around Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Tarantino’s latest release. The film itself has fueled think pieces galore, about nearly every element of the movie, precisely at a time when Tarantino’s status as a legendary auteur has been dinged a bit due to all of those old offscreen controversies. It’s become The Movie to Argue About This Summer (August edition).

Related

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is Tarantino’s fun, haunting homage to the summer of ’69

What’s fascinating is how little the three main Once Upon a Time controversies (for there are also many smaller ones) seemingly have to do with each other. One stems from Tarantino’s treatment of women in his movies. Another stems from his casual rewriting of historical events. The third has to do with his treatment of his very fictional version of the very real Asian American star Bruce Lee.

At the core of all three of these ideas is that Hollywood is still a place that largely tells stories dominated from a cisgender, heterosexual white guy point of view. But also at their core is that Tarantino is a filmmaker who loves ambiguity, who doesn’t want to have to tell you the proper way to behave, who instead prefers to work within the troubling gray areas that make up much of human existence. And if there’s an approach to storytelling that seems designed to provoke heated responses online in the year 2019, it’s one devoted to moral ambiguity.

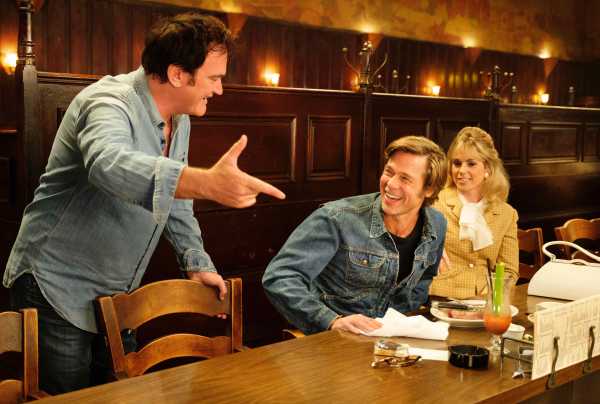

Tarantino is a major artist whose movies are worth discussing, and Once Upon a Time is a sprawling film that provides many different opportunities for potential conversation. For a little under three hours, the movie resurrects the Hollywood of 1969, embarking on a largely plotless ramble through a long-gone world. Its journey concludes with a depiction of the Manson family murders that symbolically marked the end of a Hollywood era.

But the director’s status as one of the last auteurs standing and the movie’s general critical acclaim (not to mention its amazing box office success) also don’t make him or it above criticism, especially when the movie stumbles in portraying women or people of color. The tension between those two ideas is the tension around how we talk about art in 2019 in general.

To understand all of this better, let’s break down the three biggest controversies surrounding the film, one by one.

1) Once Upon a Time in Hollywood disrespects the legacy of Bruce Lee

On July 29, shortly after Once Upon a Time in Hollywood opened on July 26, the entertainment publication the Wrap published an interview with Sharon Lee, the daughter of the great action star and martial artist Bruce Lee. Lee is a minor character in the film, played by Mike Moh. (The real Bruce Lee died in 1973, at age 32.) In the interview, Lee says the movie cavalierly mocks one of the few major Asian American stars of the period it depicts.

She said:

Chances are, if you’ve heard of just one Once Upon a Time in Hollywood controversy, it’s this one, which seems to disrespect an actual person, who has living relatives and whose legacy as one of the few Asian Americans to become a star at that point in Hollywood history has made him a figure whose cultural impact extends beyond the movies he made. (For his part, Tarantino has pushed back against Sharon Lee’s claims.)

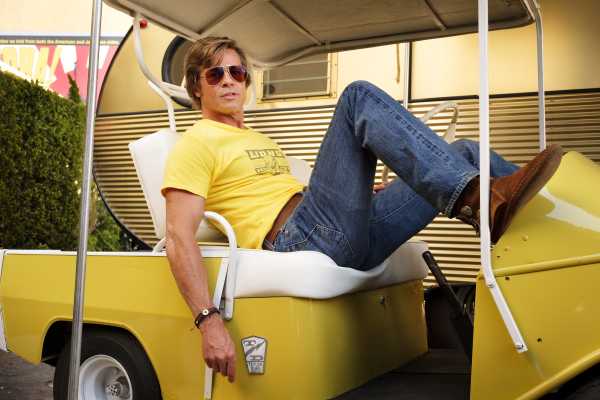

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood contains a scene in which Brad Pitt’s character, Cliff Booth, faces off with Lee on the set of The Green Hornet, a one-season pulp action TV show that ran from 1966 to 1967 and has gone on to be a cult hit (i.e., exactly the kind of thing cult movie lover Tarantino would be obsessed with). Lee is a star on the show, and Cliff is on set as the stuntman backup to his buddy Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio).

The two get into a battle of the braggarts about who is the better fighter and then decide to have a best-two-out-of-three sparring match. (Lee’s cockiness in this scene is a major part of what Sharon Lee objects to. She maintains that he tried to downplay his talent in order to make it as an Asian American man in Hollywood.) Lee dispatches Cliff easily in round one. Cliff throws Lee into the side of a car in round two (so hard that his body dents it, which might end up being important in a second). Before round three can begin, a stunt coordinator intervenes. The two men are separated, and Cliff is fired from the set.

It’s worth noting that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s co-stunt coordinator Robert Alonzo told the Huffington Post that Cliff was originally going to win the fight, after taking a cheap shot at Lee. Both Alonzo and Pitt convinced Tarantino to change the result of the fight to display that Cliff is a formidable fighter — thus setting up the ultraviolent end of the film — without having him actually beat Lee in hand-to-hand combat. With that in mind, it’s even easier to see why Sharon Lee felt the movie disrespected her father’s legacy.

But I (admittedly an extremely white person) think it’s also worth noting that it’s not precisely clear that what happens in the fight between Cliff and Lee actually happens in the reality of the film. The scene is depicted as a flashback (to 1967, from the movie’s 1969 timeline) filtered through Cliff’s memory in one interpretation and as an idle daydream he has while doing an odd job for his friend Rick in another interpretation.

If the fight is just a thing that Cliff is imagining — he could totally take Bruce Lee! Sure he could! — the tenor of the scene changes dramatically. Suddenly, it’s not a scene about Cliff being able to best Lee but one about his own self-deception regarding the ways his career has grounded itself on the shoals of changing tastes in Hollywood. And even if something like the events of the scene really did happen in the movie’s version of reality, the presence of that heavily dented car strikes me as a tell that what we’re seeing is an exaggeration, the intrusion of moviemaking embellishment into Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s hazy attempt to recreate the late ’60s as they really were.

So Bruce Lee needs to be cockier and a bigger jerk than he would have been in real life, because he needs to stand in for all that Cliff finds concerning about the Hollywood of 1969 and his own career trajectory.

But even if we say that everything that happened between Bruce Lee and Cliff Booth in that scene happened in the world of the film exactly as depicted, the scene has fans who think it offers a more human portrayal of a man who too often sees his humanity subsumed by his status as an icon.

Critic Walter Chaw argues at Vulture that the scene plays off Bruce Lee’s own career path — which involved parlaying the fame he gained from The Green Hornet into a career and rising through the ranks of Hong Kong action stars, before once again breaking big in the US right before his death. He also recognizes that much of Lee’s trademark onscreen persona became a point of mockery for many Asian American kids, who saw their white peers mimicking Lee’s fighting stance and vocalizations.

In Chaw’s view, the scene does something very different than its detractors say:

Chaw also points out that after actress Sharon Tate was murdered in the summer of 1969 but before members of the Manson family were implicated, her husband, Roman Polanski, suspected that she had been killed by the man who had trained her for combat in her most recent film (and who is briefly shown training her in Once Upon a Time as well). A man named Bruce Lee.

Which brings us to controversy number two.

2) Hey, do you need to be an expert in the Manson murders to even understand this movie?

Shortly after seeing the movie for the first time, journalist and filmmaker Emily Yoshida tweeted an interesting query:

It’s a fair point! I’m a devoted fan of the podcast You Must Remember This — which dedicated an entire season to the story of the Manson family murders that occurred in part on Hollywood’s Cielo Drive in early August 1969. So I more or less knew what was happening as Once Upon a Time in Hollywood began its ticktock through the long hours of August 8, 1969, leading up to the killings that would occur later that night. But if you aren’t well-versed in that case, or in what it meant to the larger culture (and Hollywood more specifically) of the time, it’s hard to imagine the film’s plot having the same impact.

Related

The Manson Family murders, and their complicated legacy, explained

I would argue that Tarantino does a solid job of situating viewers in the world of Los Angeles the late ’60s, and his recounting of events leading up to the murders does a solid job of inducing dread. If you only know that Sharon Tate (played here by Margot Robbie) was murdered, you’ll probably be fine. But what if you have no idea?

This is not a controversy so much as a point of discussion. And on the surface, it might sound like a silly concern. But think about it more deeply and you may come to realize that almost all the impact of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s ending and ultimate thematic concerns rests atop the idea that it is subverting history. In the movie, the Manson family decides to kill Rick Dalton (and then stumbles into their own deaths at the hands of Cliff instead) rather than going next door to murder everybody currently present at the house Sharon Tate is staying in. Vox’s Alissa Wilkinson has written more about those differences here, if you want to get into granular detail.

The core idea of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood revolves around a fairy tale, one that unwinds one of the darkest, most horrifying things ever to have happened in Los Angeles by porting it into the world of the movies, where the good guys can save the day. The movie even makes this explicit when it contrives a reason for Rick to still have the flamethrower he used on an old movie he made and then also contrives a reason for him to use it to kill one of the Manson family cultists.

But for Tarantino’s subversion to really land, you have to know the reality being subverted to a pretty high level of detail — and if you don’t, the whole story starts to feel like it’s about Rick and Cliff taking out their aggression on hippies or (more troublingly) young women. And considering both Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s issues with women and Tarantino’s issues with women (more on those below), the notion that the film is a fairy tale subversion of real history becomes stretched so thin that for many people, it snaps.

What’s more, the movie chooses to leave Charles Manson out of the story almost entirely; he pops up only one time, looking for someone who used to live in Tate’s house. Where Tarantino’s other historical subversions have ended with the deaths of Adolf Hitler (Inglourious Basterds) and an entire family of slave owners (Django Unchained), this movie lets the boogeyman continue haunting Hollywood’s shadows, to the degree that viewers might wonder if the Manson family will still commit the other murders it actually did go on to commit after killing Tate and the other people present in her home.

Related

Quentin Tarantino’s history rewrites makes his movies fit the future

Departing from the historical record isn’t a problem. Fiction is often used to right wrongs, and in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Tarantino has reconstructed a long-gone world that he seems to want to disappear into and then invented a way to make sure the ’60s never had to end. (The Manson murders are often cited as “the end” of the ’60s.) Consequently, what has drawn actual criticism is the way the movie departs from the historical record, and the characters it chooses as its objects of punishment.

Which brings us to controversy three.

3) No, like … really … does this movie hate women?

One of the weirdest pieces of criticism to surface in the wake of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s general controversy storm has been this Time piece that combs through Tarantino’s entire filmography to count how many lines of dialogue women speak within each movie. (It initially omitted Death Proof, whose cast members are mostly women and which was originally part of a longer double feature called Grindhouse, but has mostly stood on its own ever since its original release in 2007; the Time story has since been updated to include Death Proof.)

It’s a bad piece of criticism, confusing raw data with context. For instance, the Time model says that Tarantino’s third film, 1997’s Jackie Brown, features fewer than half its lines spoken by women, but the film’s protagonist — Jackie Brown herself — is such a vital and fun woman to hang out with that the feeling of watching that move is nothing like what the numbers suggest.

Still, it’s easy enough to see that Time was hoping to get at a conversation that has swirled around Tarantino for much of his career but that really gained momentum after 2015’s The Hateful Eight and has now resurged with Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Namely, does this guy hate women or what?

The answer to that question is tricky, and it’s kind of “both? Question mark?” As I alluded to above, Tarantino’s movies are full of rich, fascinating women characters, from Jackie Brown to the Bride (Uma Thurman’s role in the Kill Bill films) to the car full of young ladies in Death Proof to Shosanna, the young Jewish woman who almost single-handedly topples the Nazi empire in Inglourious Basterds. (She’s my pick for Tarantino’s best woman character, because she so ably blends his love of movie violence with his uneasiness about movie violence — more on this in a second.)

And even his more troubling films in this regard still feature women worth studying. The Hateful Eight takes a nasty glee in how often its various men get to beat up the movie’s one woman (Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Daisy). But oh, my god, it’s impossible to not watch that movie and be fascinated by Daisy all the same, as she’s a bundle of contradictions who adds up to one of the richest woman villains of the last decade. (Plus, Leigh has never been better. She received a well-deserved Oscar nomination for her efforts.)

Tarantino writes rich, complicated women, which is more than can be said of many directors who have received many more awards than him. Like, I love Steven Spielberg, but what’s the best role for a woman across his entire filmography? The mom in E.T.? Her character’s official name is “Mom.”

Here’s how BuzzFeed’s Alison Willmore puts it in her essential piece on the women of Tarantino’s movies:

My guess is that before Django Unchained — which barely features significant women characters to speak of — Tarantino’s reputation would have been “one of the better straight-guy directors when it comes to depicting women.” Yes, he has a heavily rumored (and not so heavily rumored, if you’ve seen any of his movies) foot fetish, but in terms of movie fetishes foisted on the public by straight dudes, looking at a bunch of women’s feet is pretty minor, all things considered.

Across the 2010s, however, Tarantino’s reputation has shifted from “not bad” to “kinda gross” when it comes to how he depicts women. There are many reasons for this, but I think we can boil them down to three main ones:

1) His fans are annoying. Of the three reasons, this is the one that Tarantino bears no responsibility for. But if you are at all active on social media around the time a Tarantino movie is released, then you know said film will be worshipped by the kinds of loud, braying film bros who populate too much of Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit film discussions as a kind of sacred text that must not be questioned. (Just check out the responses to this tweet!) Nuanced conversations get pushed aside, especially when it comes to how Tarantino handles, say, violence against women. If it makes you squeamish, then aren’t you the problem?

Willmore also gets at another aspect of this response in the paragraph I excerpted above. It’s one thing for a movie to contain violence against women in a vacuum. It’s another to hear your fellow audience members howl with laughter and cheer as it happens onscreen. This isn’t Tarantino’s fault, per se, but I agree with Willmore that he rarely seems to have considered how his worst audience members might react.

2) We know Tarantino’s record with even his most trusted women collaborators isn’t spotless. Tarantino has never been #MeToo’d, but he is someone whose career was essentially made by Harvey Weinstein. And when ex-girlfriend Mira Sorvino tried to tell Tarantino that Weinstein was a predator, he didn’t listen to her. Tarantino has copped to how he didn’t do enough to figure out what was going on with Weinstein, because he didn’t want to question his most significant patron.

Perhaps even more troubling is Tarantino’s lax attitude around Uma Thurman’s safety on the set of Kill Bill, where she was involved in a serious car accident that caused a concussion and damaged her knees. An experienced stunt coordinator told the Hollywood Reporter it could have resulted in a decapitation. Thurman claims that Tarantino angrily refused her a stunt performer because it would have cost too much money; Tarantino mostly disputes that he was angry.

Thurman had been one of Tarantino’s most faithful collaborators to that point, but the two have not worked together since. (Thurman and Tarantino seem to have reconciled, and Thurman’s daughter, Maya Hawke, has a very small part in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood as the one Manson girl who has a crisis of conscience and gets away.)

3) Tarantino’s most recent two films are replete with dark, horrific, occasionally humorous violence against women: Quentin Tarantino is a filmmaker who loves rubbing viewers’ faces in taboo subject matter. He’s one of the few white filmmakers whose movies have repeatedly used the n-word across his career, and on a more defensible level, his movies celebrate scumbags and reprobates.

But in his most recent two movies, he’s seriously started testing the limits of what audiences will stomach when it comes to men repeatedly hitting women and causing significant injuries. There are moments in The Hateful Eight, for instance, where Leigh’s character essentially becomes a punching bag, and because she can be so vile, some little part of you is primed to want her to be a punching bag.

Related

The Hateful Eight, Quentin Tarantino’s new film, is a deeply interesting failure

This trend only continues in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, a movie where the most significant woman character (Margot Robbie’s Sharon Tate) is best understood as a kind of vision of old Hollywood glamour, an occasionally unknowable cipher, and where many of the other women in the story exist largely to be punished.

Consider, for instance, the one-off character of Cliff’s wife, who died at some point before the film begins. (Some people suspect Cliff killed her, but he’s never been convicted.) She’s hectoring him on a boat the one time we see her, in yet another unreliable flashback whose veracity is impossible to determine. Confident Cliff looks sad and beaten down by her barrage of insults. But we never find out if he’s actually responsible for her death.

Here’s how Angie Han of Mashable put it in a piece talking about how impossible it can be to prevent real-life context surrounding Tarantino — as well as Brad Pitt, who plays Cliff — from creeping into your thoughts as you watch this movie:

To some extent, there are questions about misogyny and sexism present with every single woman in this movie. You could very well argue, based only on Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, that Tarantino is a terrible misogynist who has come to hate women in the past several years of having his intentions questioned. You could also make the case that Tarantino is trying to earnestly depict the misogyny present in Hollywood and in America both in the late ’60s/early ’70s and right now, and that he’s trying to complicate your view of a cool dude like Cliff by making you wonder if he killed his wife.

I would again opt for small-child-saying-why-don’t-we-have-both dot GIF. The intentional ambiguity surrounding Cliff’s past is a great get-out-of-jail-free card for Tarantino, because any time you think you have the movie’s attitude toward women pinned down, it veers off in a new direction. Cliff is the movie’s hero; he’s also possibly a murderer. All too often, loving Hollywood and the movies means loving something horrible at its core. If you love Kill Bill, you’re also loving a movie where the director’s attitude toward safety nearly killed his star.

Where Once Upon a Time in Hollywood gets away from itself for me is in the ending, which features shockingly abrupt and horrible violence against women, in this case two of the Manson girls who murdered Sharon Tate in our reality and who attempt to murder Cliff and Rick in this movie’s reality.

The easy argument here is, “Listen, these women brutally killed a pregnant woman. They deserve what’s coming to them.” And sure. Maybe. Cliff is certainly defending himself when he kills them instead — but you’re also not exactly supposed to find it a grim, but necessary, act when he whips a can of dog food into one of their faces. You’re supposed to think it’s fun.

And that’s to say nothing of how the three people who are mercilessly killed in this scene (one of whom is a man named Tex, let’s not forget!) are operating at the behest of another man, Manson, who isn’t even there. Tarantino takes a dark and horrible crime and all but removes the responsibility of the cult leader who made it possible by simply scrubbing him entirely.

To get to a point where it feels at all defensible for these two women to be killed in such horrible fashion involves wading so deep into the subtext as to end up in over your head. And to be clear, I’m comfortable doing that. I’m more than happy to explain how Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s fantasia of violence is a necessary corrective to the way Hollywood became a little less itself in the immediate wake of the Manson murders, to mull how the movie serves as an invitation for a certain era of moviemaking to never end.

But I’m a lot less comfortable with the way the guy sitting three seats away from me whooped and hollered and shouted, “Yeah!” with relish when that girl got brained by the dog food can. The subtext is great. The text is still women getting the shit beat out of them.

Ambiguity and you, or “I guess Quentin Tarantino just wasn’t made for these times”

Before we continue, I want to state for the record that I’m really uncomfortable with the paragraph above, because it’s really difficult to convey these concerns in a way that doesn’t sound like l’m saying “No violence against women in movies ever!” If filmmakers are expected to constantly answer for the worst things their audiences might ever think, no art of value would ever get made.

But I still struggle with the way the ambiguity of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood — one of the qualities that makes it a movie worth thinking and talking about — has also made it such an object of endless debate. Some debate is inevitable and valuable, I think. Tarantino might be a great filmmaker, but he’s just one guy, limited by his perspectives. Hearing how people of Asian descent and women take issue with certain elements of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood can help all of us better understand how the limitations of a director’s perspective can make it harder for some viewers to embrace his vision.

What worries me is that sometimes these conversations evolve from “I was uncomfortable with the way this film depicted violence against women” to “I wish that somebody in the movie had said the violence was wrong” with barely an acknowledgment of the movie’s central, essential relationship to its own ambiguous heart. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is not a movie that wants to impart a moral. It’s a movie that wants to deposit you into a faithfully recreated version of a bygone time and place and then jarringly remind you that it’s just a movie, that you cannot get back to that bygone time and place, that you are watching something impossible.

I think it’s telling that the reason the Manson girls (and Tex) go after Rick and Cliff is that Rick was in a TV Western, and the Mansonites make a half-formed argument that it was TV that taught them to kill and, thus, by killing Rick, they’ll be righting a wrong. But when they head up to the Cielo Drive house to kill Rick, they are killed instead. Violence begets violence, but violence also solves violence. These two ideas are enmeshed within Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and movie history and human history.

You’re not supposed to leave this movie feeling like everything was resolved in the end, is what I’m saying. If you feel discomfited by the violence against women, that’s at least a part of the point, and if you cheered on that violence, that’s also at least part of the point. None of what you see is supposed to make you feel any better. Neither is the fact that a story where the famous people haunting the edges include a woman and an Asian American who both became stars but who ultimately have their stories eclipsed by two fictional white guys past their prime.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood ends with Rick being invited into the home of Sharon Tate, something he’s been hoping will happen for ages. It’s meant as a kind of warm and inviting chance for the sorts of cult figures that Tarantino has long idolized to step out of the shadows and into the limelight. But the sorts of B-pictures that Rick made — the Westerns and war films and low-rent action movies — were eventually going to enter the big Hollywood tent, welcomed by the likes of Steven Spielberg, who would pave the way for them to eventually take over. One way or another, old Hollywood was going to end, no matter what happened on the evening of August 8, 1969.

The real lesson, then, might be how hard it is for a movie — or for any work of art — to embrace ambiguity in a time when we ask, more than ever, for art to have moral clarity, by which I mean a forthright statement of what is good and what is bad and so on and so forth. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with moral clarity in art, but I also don’t think it’s strictly the responsibility of art, which has more often aimed to complicate the way we think about the world than to coddle us. Asking art to fulfill the same role that religion and moral philosophy has traditionally filled is a fool’s errand.

Not liking Once Upon a Time in Hollywood for literally any reason is fine. I feel hugely mixed on it and find a lot of it hard to take. But the conversation around the movie — the not-so-quiet concern that because this or that element isn’t easily digestible, the film must be “bad” — suggests that what too many people want more than ever is art that comes pre-chewed. That has its place and time, but we also need to be challenged. Thank goodness for movies that are willing to do that, even when we hate them.

Sourse: vox.com