Deep in the heart of conservative Texas lies its liberal capital of Austin — a city jokingly referred to as “a blueberry in the tomato soup of Texas.” Given its left-leaning politics, it might seem strange that of Austin’s six congressional representatives, five are Republican.

That’s because during 2011 redistricting, Texas Republicans effectively diluted the voting power of Austin — and the equally liberal Travis County it sits in — by splitting the county into five congressional districts and carving Austin into six districts.

But with signs of a blue wave potentially ready to hit Texas along with the rest of the country during the 2018 midterms, some political observers are wondering whether Texas Republicans’ dramatic gerrymandering could backfire. Austin voters now have the potential to erode Republican margins in each of the five Republican-controlled districts and perhaps even flip one — the 21st Congressional District.

“Partisan mapmakers tend to overreach,” said elections analyst Dave Wasserman, the US House editor of the Cook Political Report. “Just because the plan has worked well until now doesn’t mean it will work well in 2018.”

What do we mean when we say Austin is gerrymandered?

Every 10 years, officials in each state redraw their congressional districts after the US Census in order to reflect population changes. But Republicans redrew Austin’s districts strategically, portioning off parts of the city and linking them to outside, conservative counties. They did this to ensure sure Travis County Democrats couldn’t have too big of an impact on election results — a tactic that’s referred to as “cracking.” (The opposite tactic is called “packing,” when you cram members of the opposite party into fewer districts.)

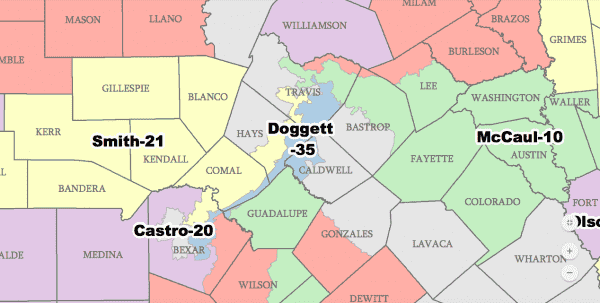

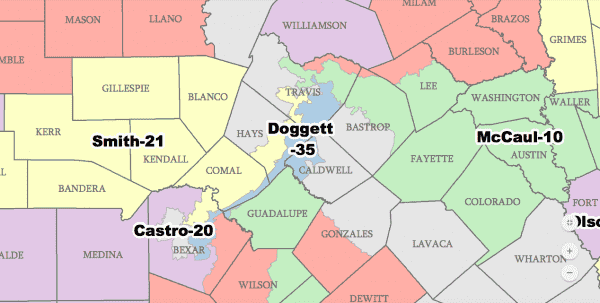

Each of Austin’s congressional districts essentially has a little slice reaching down into Travis County but is completely swallowed by the surrounding conservative counties. Austin’s six districts are as follows:

- Congressional District 10 — Rep. Michael McCaul (R-TX)

- Congressional District 17 — Rep. Bill Flores (R-TX)

- Congressional District 21 — Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX) — retiring

- Congressional District 25 — Rep. Roger Williams (R-TX)

- Congressional District 31 — Rep. John Carter (R-TX)

- Congressional District 35 — Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D-TX)

Two of the city’s congressional districts each contain about 24 percent of city residents (CD-35 and CD-10), another has 22 percent of Austin residents (CD-21), the fourth has 19 percent (CD-25), and the last two districts each had less than 8 percent of city residents (CD-17 and CD-31).

“Austin was specifically drawn by the Republicans to not be able to affect elections,” said Harold Cook, a Democratic political analyst based in Austin.

So how can a wave change all that?

Come the 2018 midterms, Democrats have their sights set on three other districts nowhere near Austin; the Seventh Congressional District in Houston against incumbent Rep. John Culberson, the 23rd Congressional District outside San Antonio against incumbent Rep. Will Hurd, and the 32nd Congressional District in Dallas against incumbent Rep. Pete Sessions. Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump in all three districts in the 2016 election.

The fact that super-liberal Austin isn’t on this list speaks to how gerrymandered the city is.

And though it’s highly unlikely Austin voters alone will be able to flip solid GOP seats from red to blue in most of its six districts, political scientists and Democratic Party insiders alike believe they have a shot (albeit a long one) at turning the tables in the 21st Congressional District. That’s the only one with an open seat after Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX) recently announced he would retire; there are currently 18 Republican candidates in the running, as well a competitive field of four Democrats.

“The Republican side is just a jungle,” said University of Texas Austin political professor Jim Henson. “In a primary that’s that crowded, there’s a certain random element of who comes out of it.”

CD-21 is the voting place of about 22 percent of Austin’s residents, and if they turn out in droves in November, they could have an impact. Henson and other political scientists say a number things need to go very well for Democrats in order for them to flip the district. But especially given how rapidly Texas’s demographics are changing, residents could erode the Republican edge in all of their districts.

“Austin has all of the districts to lean into,” said Mark Jones, a political science professor at Rice University in Houston.

Is what Republicans did with Austin legal? The US Supreme Court still needs to decide.

Redistricting is officially meant to reflect population changes, but state lawmakers in Texas and a number of other states redrew the boundaries of their congressional districts according to a practice called partisan gerrymandering, where district lines are redrawn to protect one particular party. Wisconsin and Maryland both have partisan gerrymandering cases before the US Supreme Court, and the Court recently agreed to consider a case in Texas too.

But there’s an important distinction between the Texas case and the ones in Wisconsin and Maryland. A federal three-judge panel in San Antonio ruled last year that Republicans in the Lone Star State had committed racial gerrymandering, discriminating against voters of color. This is generally considered illegal under the Voting Rights Act, though there are some exceptions for states to do this if they can demonstrate proper cause.

The Supreme Court decided another racial gerrymandering case last year, ruling that North Carolina had violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment by separating voters into districts on the basis of race without “sufficient justification” for doing so. The justices affirmed lower court rulings telling North Carolina to redraw its maps fairly.

The Texas judges ruled the lines had to be redrawn in August, but Republicans appealed and the case was taken up by the US Supreme Court in January.

“It screwed minorities, is the short version,” said Austin attorney Max Renea Hicks, one of the lawyers on the case representing minority groups that are plaintiffs. “They chopped up the minority population so that in Travis County, the minority population essentially has no say in the elections.”

The phrases Hicks uses to describe the congressional districts in and around Austin give you an idea of how the maps look. He called one district “a pinwheel in the middle of Austin,” and another “a sneaky little arm.”

It’s possible there could be a Supreme Court decision on the Texas map before the general election in November, but Democrats aren’t holding their breath. And for the most part, political observers in the state think Republicans will probably still come out of this election cycle retaining their power.

But there’s also an element of uncertainty driven by the rapid demographic change coming to Austin and the areas around it, combined with “unbridled” Democratic enthusiasm that’s gotten Democratic candidates running in each of the state’s 36 congressional districts for the first time in 25 years.

Why Texas Republicans are looking more vulnerable than they’ve been in a long time

Like the rest of the country, Texas could be hit with a blue wave in this year’s midterms. Two big things are driving this in the Lone Star State: demographic changes and dislike of President Trump.

“I guess we’re about to find out together whether [Republicans] cut their margins too thin or whether it’s going to work out okay for them,” Cook, the Democratic political consultant, told me, though he remains skeptical Democrats will actually win.

It’s worth taking a step back to point out that none of these conversations would be happening if any other Republican were president besides Donald Trump.

The president’s approval rating in Texas is noticeably low — 39 percent, as opposed to the 54 percent of Texans who say they don’t like him. This may seem surprising at first blush, given that Texas is thought of as the home of conservative politics. But the state has a lot of college-educated, affluent, suburban voters, who historically don’t like Trump that much — especially suburban white women.

The state is also experiencing an influx of Hispanic and Latino voters. The 2010 census showed about 51 percent of the state’s overall population is Hispanic or Latino. An influx of 2.7 million new Texans has come into the state since 2010; more than half are Latino.

“The fact we’re even discussing this has to do with how much Donald Trump has damaged the Republican brand,” said Cook. “Two years ago, if you’d mentioned any of this real estate except for the Will Hurd seat [in CD-23], you would have been laughed out of the room by political science professors in each party.”

Sourse: vox.com