Share

Tweet

Share

Share

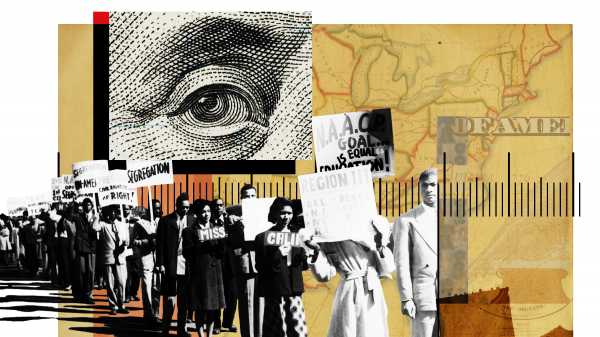

How “movement capture” shaped the fight for civil rights

tweet

share

Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

Social movements usually start out on the fringe, without a lot of resources, credibility, or public support. When they get more of any of those, that’s a good thing … right?

Well, yes … and no. When a movement grows in funding and mainstream appeal, it has the chance to achieve more of its goals — but often, the goals themselves are changed by the influx of new people and the preferences of new funders.

Is that part of the natural progress of a social movement from unheeded outsiders to part of a coalition big enough to win important victories? Or is it a tragic loss, where the most important goals get tossed aside in favor of ones more palatable to a mass audience? Are organizations building a coalition — which necessarily entails some compromise — or are they getting steered off course?

A new paper by Megan Ming Francis at the University of Washington explores the power that wealthy funders have to change the direction and the priorities of the organizations they fund. She calls this “movement capture” — the phenomenon where activist groups end up pressured by well-intentioned funders into a change in course.

Francis explores how the NAACP’s priorities were changed by funders in the early 20th century, and how the organization’s focus today is still shaped by those early funders. She’s interested in whether the same thing is happening with Black Lives Matter and its funders today — and the dynamic she describes is one that can play out wherever there’s an underfunded local advocacy effort and wealthy, powerful funders with different priorities.

“I’m concerned that sometimes even with the best of intentions, the priorities of the poorest and marginalized get replaced by the priorities of the rich and powerful,” Francis told me.

How the Garland Fund changed the NAACP

Founded in 1909, the NAACP is today particularly well-known for its work on black education and economic opportunity. But in its early days, it actually had an aggressive focus on anti-black violence, working to get anti-lynching bills through Congress.

“From the viewpoint of the NAACP, before the organization could appropriately address other problematic areas of civil rights such as voting, labor, and housing, it was necessary to focus on ending lynching and mob violence,” Francis writes. The early NAACP believed that violence had to be tackled first — that victories in other areas would essentially be hollow until violent terrorism directed at black people had been addressed.

But by the 1920s, that had changed.

“The NAACP, who viewed safety from mob violence and lynchings as the pinnacle civil rights struggle of the twentieth century, was severely underfunded by 1925 and without any viable prospects of big donors to support its anti‐lynching activism,” she writes. As the paper notes, the NAACP couldn’t get any organizational support if it wanted to focus on violence. But it could get grants if it wanted to focus on black education.

Enter the Garland Fund. The Garland Fund was in many respects an unusually good charitable foundation. Charles Garland, the son of a Wall Street stockbroker, inherited a $1 million, tried to refuse it, and instead decided to give it all away.

Garland directed the fund’s administrators “that the money should be distributed as fast as it can be put into reliable hands,” in contrast to many foundations, which seek to sustain themselves indefinitely, dispersing only a small share of their money. While foundations in the early 20th century were often openly racist, Garland demanded that his giving be “to the benefit of mankind — to the benefit of poor as much as rich, of black as much as white, of foreigners as much as citizens, of so‐called criminals as much as the condemned.”

Garland’s organization also started out with a firm commitment to not “attempt by promise or by the setting forth of conditions or by any other means to control the policy of any group or individual entrusted with this money or a part of this money.” That, though, eventually changed, according to Francis.

The Garland Fund was most interested in education and organized labor, two areas it saw as the most important foundations for improving society. Over time, according to Francis, it discouraged the NAACP’s work on racial violence in favor of a focus on black education, and effected a swing in priorities that still guides the NAACP today (though the fund stopped operations in 1941).

The NAACP’s focus on education brought about some of the most important civil rights advances of the 20th century, including the landmark school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education. That makes analysis of the relationship between the Garland Fund and the NAACP fascinatingly complex. If a good outcome — a huge win for civil rights — resulted, how should that change our thinking about the Garland Fund’s priorities and how they influenced the NAACP?

Francis points to evidence that black leaders at the time didn’t think of desegregation as the pivotal success that we see it as today. Other researchers have emphasized that the fight for Brown was somewhat out of step with what black communities prioritized at the time.

“[W.E.B.] Du Bois” — one of the founders of the NAACP — “was moving away from education to a ‘racial program for economic salvation,’” Francis points out, “and had become deeply skeptical that black students would ever receive decent treatment in white schools.” Seventy years after Brown v. Board of Education, it’s not hard to see why black leaders at the time thought there was an even better approach to the fight for civil rights.

Francis argues that even when “movement capture” results in genuine and incredibly important policy victories, it’s important to keep an eye on what was lost — and to be aware of how much sway these powerful funders have. And she points out that claims that the course history took was the best possible outcome for civil rights seem overconfident. Maybe we could have had anti-lynching laws sooner and leveraged that success to achieve desegregation.

“They achieved this dramatic, important thing,” she said, emphasizing that no one should conclude from this complicated story that Brown was a bad thing. “But I do wonder about how different the trajectory of civil rights would have been if we’d listened to black activists at the time.”

How “movement capture” happens

One might think that you can hardly make an organization worse off by giving it money — even with strings attached. But organizations have limited time and energy and management resources, and if those are focused on expanding one priority, other priorities will suffer.

And even if an organization that gets funding from someone with very different priorities is still technically better off than one that gets no funding at all, it might be the case that they’ll fall far short of their potential had they secured less — but also less restricted — funding.

Francis argues that you’ll see movement capture whenever there are private funders with different priorities than the organizations they’re funding, using their influence to redirect the organization’s focus and energy. She worries that funders often assume they have a better picture of the problem when they might not — and she thinks funders underestimate the costs to the movement of grassroots organizations aligning themselves with the funding zeitgeist.

“That’s the conundrum of contemporary philanthropy,” she told me. “It’s not bad that we have these so-called thought leaders. It’s not bad that there’s the work being done by [George] Soros, or by other groups, on work they think is genuinely important. But what was concerning back in the 1920s, and what I think is still concerning today, is the way that exciting localized social justice organizations get co-opted by funders.” Sometimes, the only work that ends up happening is the work that attracts enthusiasm among the wealthy — and critical perspectives end up missing.

All of this, Francis told me, happens even when funders have the “best of intentions” — and can happen even when they’re genuinely committed to the same priorities as the organizations.

How can we do better? Francis argues that funders need to consciously prioritize the voices of people on the ground, and to be more willing to make grants that may not immediately produce an obvious, palatable win they can present to their board.

My biggest takeaway is that funders ought to be conscious that funding will have side effects. Any analysis of the benefits of a grant that doesn’t take into account questions like these will end up overly simplistic, and obscuring one of the most important effects that funders have on organizations. Big funders change the spaces they work in. They need to take that into account.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Sourse: vox.com