You can think of the Center for American Progress’s Medicare Extra plan as simultaneously trying to answer the leftist critique of Obamacare and the centrist critique of Medicare-for-all.

Like Medicare-for-all — and unlike Obamacare — it’s universal, it uses Medicare’s pricing power to hold down costs, and it rebuilds the entire health system around public insurance. But like Obamacare, it’s designed to minimize middle-class tax increases while stepping gingerly around people’s fear of change and mistrust of the government. And so, unlike Sen. Bernie Sanders’s Medicare-for-all bill, it holds on to much of the employer-based private insurance market and includes means-tested premiums and cost sharing for all but the poorest Americans.

“We were balancing two considerations,” says Topher Spiro, vice president for health policy at CAP. “One was employer coverage, particularly large employer coverage, is working for many people and they’re satisfied with it. They fear disruption, whether that’s rational or not. But there’s also this trend of increasing deductibles in employer coverage, which we address by allowing [both employers and individual employees] to opt into the Medicare plan.”

According to an analysis CAP commissioned from the independent health care consulting firm Avalere and provided exclusively to Vox, Medicare Extra would achieve universal coverage — adding 35 million people to the insurance rolls — while cutting national health expenditures by more than $300 billion annually.

Avalere, which uses a methodology meant to mimic the Congressional Budget Office’s approach, also estimates that Medicare Extra would cost the government between $2.8 trillion and $4.5 trillion more than it’s spending now over the first 10 years, depending on how you structure the cost sharing. CAP is quick to note that at the lower range, the plan could be financed entirely through wealth taxes and other levies on richer Americans.

That said, the true costs of the plan would be somewhat higher. Because Medicare Extra takes about four years to phase in, a 10-year cost estimate underplays the actual running costs; once the program is up and running, it will spend about $400 billion to $500 billion per year.

Avalere projects that by 2031, almost 200 million Americans would be on the Medicare Extra plan, with another 121 million in employer-sponsored coverage and 33 million keeping original Medicare. So while Medicare Extra would be the dominant insurer, it wouldn’t be the only insurer. In this, CAP’s plan inverts the status quo: It’s a public system with some private options, rather than a private system with a few, often inaccessible, public options.

So how does it work? Let’s run through the details:

- Medicare Extra builds a new public insurance program called, well, Medicare Extra (the branding leaves something to be desired). The new plan shares Medicare’s name, but its benefits are much more expansive: It includes, for instance, vision, dental, and reproductive health coverage.

- Premiums are on a sliding scale, with Americans under 150 percent of the poverty line paying nothing while those making 500 percent of the poverty line or more see their total contribution capped at 9 percent of income. Cost sharing, too, varies by income, total out-of-pocket spending, even for the richest, capped at $5,000.

- Newborns would automatically be enrolled in Medicare Extra, as would the uninsured and every legal resident upon turning 65. Medicaid and Obamacare would be folded into the new program, and anyone on traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Tricare, Veterans Affairs coverage, the Federal Employee Health Benefits Program, the Indian Health Service, or employer-sponsored coverage could opt in. Given Medicare Extra’s benefits and subsidies, Avalere expects that most people will move to ME within a few years.

- The plan saves money by expanding Medicare’s pricing power throughout the system. Medicare Extra sets hospital prices at 110 percent of what Medicare pays now and everything else at current Medicare rates (though it tweaks rates up for primary care and down for specialty care). Importantly, the plan extends those prices to employer-sponsored coverage: It’s the first of the major Democratic proposals to rely on a version of all-payer rate setting. In doing, it achieves the pricing savings you see in Medicare-for-all, but without cutting private insurance out of the system.

- In a nod to the fears swirling around single-payer, Medicare Extra wouldn’t abolish private health insurance. If you like your employer-based plan — or traditional Medicare, or VA insurance — you can keep it. In addition, the proposal also envisions private options within the new Medicare Extra plan; these “Medicare Choice” plans would have to offer the same benefits as Medicare Extra, but Medicare would only reimburse their costs at 95 percent of the program’s rates.

- Everyone in the system, from individuals getting insurance from their employer to traditional Medicare enrollees, could choose to purchase Medicare Extra instead, and they’d be eligible for normal subsidies and employer cash-outs if they did so. That’s not how Obamacare works now, for instance — you can’t convert the money your employer is spending on your health insurance to buy a better plan on the exchange.

The idea is that if you like your health insurance, you can, for the most part, keep it — but why would you?

The benefits of single-payer without the costs?

The question lurking behind CAP’s Medicare Extra plan is simple: Can health reformers have it all? Can they have the coverage and efficiencies of single-payer without the disruption, taxes, and political opposition a wholesale remaking the current system entails?

Adam Gaffney is a pulmonologist at the Cambridge Health Alliance, an instructor at Harvard Medical School, and president of Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for single-payer. When I asked him about Medicare Extra, his response was measured. “It’s a public-option plan,” he said, “but it’s the most robust of the public-option options. It would in fact achieve universal coverage. The other public options can’t claim that.”

Gaffney had two main criticisms of the plan. The first was that it continues using premiums, copays, and deductibles to pay for insurance, while Sanders’s plan, which he prefers, runs all financing through the tax code, doing away with deductibles and copays entirely. “We’re still talking about thousands of dollars a year in cost sharing under Medicare Extra,” Gaffney said.

But Sanders’ plan requires tax increases most Democrats consider lethal. Both polling and experience (see the collapse of Vermont’s single-payer effort, for instance) show that the upfront cost of converting private health spending into new taxes can turn the public against reform. CAP wanted a plan with a lower price tag. From there, the tradeoffs are straightforward. “Health care is paid for by premiums, taxes, and cost sharing,” Spiro says. “If you hold premiums or taxes down, then cost sharing for higher-income people will be higher.”

Gaffney, for his part, admits the tension here. “There is some truth to the fact that the higher the taxes are, the more political opposition there’ll be,” he says. “It’d be wonderful if we could propose Medicare-for-all without tax increases, but we can’t. That’s just math. But I think we should propose the strongest policy and try to create the constituency to achieve it rather than the other way around.”

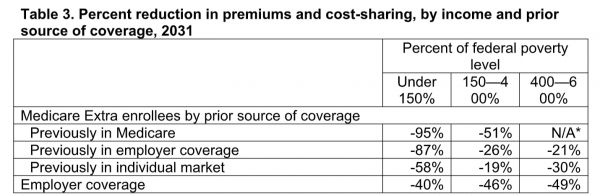

Still, it’s worth noting that both premiums and cost sharing are far lower under CAP’s plan than in the current system. This table from Avalere suggests that virtually everyone sees significant savings, though that’s before taking new taxes into account:

The other argument Gaffney makes is that in preserving a significant role for private insurance, Medicare Extra keeps insurer profits and administrative waste that could otherwise go toward reducing premiums or expanding coverage.

It’s true, he said, that in getting rid of the individual and small business insurance markets, a lot of the worst complexity and overhead would dissolve. But keeping both employer-sponsored insurance and a private option inside Medicare Extra would mean the full administrative savings possible under single-payer would go unrealized. “That’s a disadvantage,” he said.

Health wonks argue endlessly over the role of administrative overhead. Some say Medicare spends too little on things like fraud prevention and outreach, and thus the low overhead is costing money. Others, like Gaffney, say most private overhead is lighting money on fire and the system would be fine in its absence. I tend to think the single-payer advocates have the better of this one: Administrative costs are about twice as high in America as in Canada, and there’s little evidence that Canada is suffering under a crisis of insufficient billing bureaucracy.

One question that Medicare Extra’s design raises is whether it matters. After all, Medicare Extra itself should maintain Medicare’s low administrative overhead, and in a system where any individual or employer can opt into Medicare Extra, if private administration boosts costs without improving quality, won’t people just switch to Medicare Extra, which will see the benefits of those savings?

In general, I suspect Gaffney’s right that true single-payer could cut costs more sharply than even a Medicare Extra-style hybrid system. The more of a role there is for private insurance, the more leverage points there are for providers and insurers to try to boost payments by lobbying Congress. Of course, if you believe private insurers are so powerful that the political system can’t restrain them, that’s obviously also a problem for any plan that tries to get rid of them outright.

So no, health reformers can’t have it all. But the concern is that by changing too much, too fast, they may end up with nothing at all.

The power of the status quo

On Wednesday, Bernie Sanders marked Medicare’s 54th birthday by making the case for Medicare-for-all. “In my view, the current debate over Medicare-for-all really has nothing to do with health care,” he said. “It has everything to do with greed and the desire of the health care industry to maintain a system which fails the average American, but which makes the industry tens and tens of billions of dollars every year in profit.”

Sanders is voicing one side in a long-ranging debate: Is the politics of health care simply the people versus industry? Or is it just as often reformers versus the public’s fear of reform?

Many longtime participants in health reform believe it’s the latter. “You’ve got two groups that pose a problem for reformers like me, and they’re both substantial political juggernauts,” says Jacob Hacker, a Yale political scientist who has studied the history of health reform and helped construct the Medicare for America plan. “One is interest groups that benefit from private insurance, and the other is the public. You can do this in a way where most people are paying less, but most people don’t know how much they’re paying now. That’s a big deal. And people’s status quo bias when it comes to losing their plans is big.”

Hacker’s point about public knowledge is a big deal. Employers, for instance, tend to pay in excess of 70 percent of the cost of employee health coverage. Standard economic theory says that comes out of wages, so if you move it all into taxes, it all comes out in the wash. But since employees often don’t know how much employers are paying for their health care, moving the health costs employers are quietly paying on their behalf into taxes they’re paying directly feels like a huge tax increase, even if systemwide health costs are falling.

You can see these political concerns in Sen. Kamala Harris’s winding path on health reform. She entered the 2020 primary in strong support of Sanders’s Medicare-for-all plan, and of abolishing private insurance. She’s since gone back and forth a bit on abolishing private insurance and is clearly uncomfortable with the issue. Then she promised that health reform wouldn’t include any middle-class tax increases, which flatly rules out Sanders’s bill. (Sanders, to his credit, has said that there will be middle-class tax increases.)

The health industry is a problem for reformers, make no mistake about it. But the reason they’re so powerful is that the public is cautious when it comes to health coverage: Government takeovers and new taxes scare them. That public fear is powerful material for the health industry to work with, but it also exists on its own terms: Americans don’t much trust the government, they don’t like to pay taxes, and many reformers believe that for a plan to pass, it has to make concessions to those fears, not dismiss them.

This is the needle CAP’s plan is trying to thread. They’re trying to extend the benefits of wholesale reform while keeping the tax increases quarantined to the well-off and making sure most people don’t feel the government is taking anything away from them. The idea is to lure people into Medicare Extra, not force them into it.

But taking a step back, this means Democrats now have two major plans that offer truly universal health coverage, albeit in different ways and with a different set of trade-offs. That’s quite a contrast with the Republican side of this debate, which is pursuing a legal case to eliminate the Affordable Care Act, and policy options that would leave tens of millions uninsured.

Sourse: vox.com