Face value

How tattoos on foreheads and cheekbones turn unknown teens into internet stars.

By

Kaitlyn Tiffany@kait_tiffany

Feb 28, 2019, 8:30am EST

Illustrations by Shanée Benjamin

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

Face value

tweet

share

The grace of God is inked into the skin above Justin Bieber’s right eyebrow.

It’s been several years since the repentant pop star found religion, but only a few months since the teeny-tiny wisp of a shoutout appeared on his face — so small that it took eight weeks for the professional snoopers at People magazine to figure out what it said. The word “grace” is there, though, in elongated middle school cursive, so faint you might think it’s not a tattoo at all.

This is, I think we can all agree, the moment in which face tattoos became thoroughly mainstream, and not the moment in which a floppy-haired YouTube sensation turned international pop star — now married and evangelical — became alt.

Bieber isn’t the source of the cultural shift; he’s the proof of it.

It’s possible he got the idea for a brow bone tribute not from his own mind but from Instagram, where celebrity micro-tattoo artists have been busily making their names for the last several years, sharing pictures of fine-lined tattoos on fingers and temples. Or he could have been inspired by his wife, Hailey Baldwin Bieber, who has 18 of the ultra-tiny tattoos popularized by her supermodel cohort. Or one of the major-label, market-tested female pop stars who got the idea from each other: Little Mix’s Jesy Nelson, who got a queen of hearts by her ear last December, nearly identical to the queen of diamonds tattoo pop singer Halsey got in June 2018 and literally identical to the queen of hearts tattoo R&B singer Kehlani got in the summer of 2015. None of whom, obviously, is the source of the trend either.

Face tattoos have been the subject of broad interest and scrutiny in the past year. Most notably, they’ve been picked up as a hallmark of those making SoundCloud rap — a genre best defined by the way it moves the escalation points of budding careers closer and closer together.

Face tattoos fuel this escalation, in that they make a new face instantly recognizable. On Instagram, in YouTube videos, in clips pulled out of YouTube videos to go viral on Twitter. They render the face a cross-platform commodity. For a boy with Benjamin Franklin tattooed on his face (and the SoundCloud logo on his arm), they connect the dots as he appears on an Instagram account with 2 million followers, then in a parody video that gets picked up on Twitter, and then on the cover of XXL’s prestigious “Freshman” issue. And they connect the dots between a nobody YouTuber and Justin Bieber.

Face tattoos are a centuries-old tradition in some indigenous cultures, most famously the Māori of New Zealand and their intricate swirling linework, but in Western culture, the association has long been jail, gang affiliation, or “deviance” of some kind. Boldface lettering denoted slavery in ancient Rome, and face tattoos made reference to criminality when they were popularized by men in American prisons in the 1970s. The best-known were gang symbols (often acronyms or numbers), records of time spent (cobwebs, clocks, dots), or acknowledgments of specific violent crimes, mostly murder (teardrops and crosses).

A somewhat prurient broader interest in the meaning and autobiographical referents of face tattoos didn’t bubble up in popular culture again until rapper Lil Wayne and his artistic peer class — Birdman, the Game, Rick Ross — started getting teardrops and crosses on their cheekbones in the mid-aughts, signifying various types of death and tragedy. While to many the tattoos recalled the prison ink of decades past, Lil Wayne entered prison in March 2010 with those drops, and the vast majority of his 300 tattoos were done by one woman with a riverside tattoo shop in Florida.

But Lil Wayne did have a gang affiliation. He did go to prison. He also made “Lollipop,” a song so unavoidable that even the most isolated, ambivalent American suburbanites were familiar with it. He was the leader of rap’s gaudy, giddy pre-recession mass culture ascendancy, and his widely protested prison sentence coincided with the economic downturn’s bleak aftermath. And so he became a lot of things, including the primary reference point for the idea of getting a tattoo on your face.

Now face tattoos are “happening” again, a testament to Lil Wayne’s legacy and to the enduring sardonic energy of Gucci Mane’s choice, in 2011, to cover half of his face with an ice cream cone. This time, we’re looking at a new wave of inked-up kids tightly associated with the DIY music platform SoundCloud, a place where kids raised on emo and pop-punk and Lil Wayne are gathering to make mumbly rap about hating their lives. These are musicians who get famous so fast, as the Ringer’s Lindsay Zoladz put it, “we can sometimes watch their face tattoos accumulate in real time, like a fast-motion video of a wall being graffitied.” Translated to Instagram, where they all have significant presences, their faces become low-cost advertisements for careers that haven’t yet taken shape.

That was the case with Post Malone (15 million Instagram followers), the 23-year-old Texas rapper whose face tattoos — particularly “Always Tired” written under his eyes — appeared after his first viral SoundCloud hit in 2015 but before his first No. 1 on the Billboard charts, and have become such a familiar cultural image that dozens of different temporary versions are now available for sale on Etsy. It is also the case for Arnoldisdead, a 23-year-old LA rapper and producer who is, perhaps not coincidentally, more popular on Instagram than he is on SoundCloud: He has Anne Frank tattooed on the left side of his face, and Anne Frank has a marijuana leaf tattooed on her tiny tattoo cheek, and he actually calls her “Xan Frank,” in honor of Xanax.

The anti-anxiety medication is one of SoundCloud rap’s central concerns, as well as branding devices. Lil Xan, the 22-year-old California sad-boy rapper whose face decorations started with his mom’s name under his left eye, calls his fans the Xanarchy Gang. He now has 11 face tattoos, including the year he was born (1996, baby!), the words “lover” and “soldier,” and a ring of black slime dripping from his right eye, which he debuted on Instagram. “I do this for me,” he wrote in the caption. “I could care less if this makes me ugly because that’s what I was going for.”

Lil Xan has “Memento Mori” on his forehead in honor of rapper Mac Miller, who died in September 2018, as well as a line of dots down his nose in mimicry of XXXTentacion, an unfathomably popular rapper who died the same year. He has a Xanax tribute too, of course, having taken the drug as his namesake.

In simple terms, if you were trying to become a famous rapper in the internet age, a face tattoo looks like a good way to do it. Even better if it in some way pays homage to an already-famous person, or an icon of similar clout. For example: a brand-name pharmaceutical.

In one decade, a face tattoo has gone from a symbol of street credibility to a red flag for “industry plant”

For another: the Apple logo. Singer Dominic Fike has it tattooed underneath his eye, and if you do not know who he is, please don’t worry, as the main thing anyone knows about him is that he has the Apple logo tattooed underneath his eye. (He also has the initials of his Florida crew, Lame Boys ENT, on his forehead.) Last summer, the 22-year-old was at the center of a major-label bidding war, despite having virtually no music available online, never mind a viral hit. “It was as if [Columbia Records] had thrown a reported $4 million to a ghost,” Elias Leight later wrote for Rolling Stone.

In other words, in one decade, a face tattoo has gone from a symbol of street credibility to a red flag for “industry plant.”

If all of us were, all the time, reading sociology papers, this might have been less surprising. In 1999, Cambridge sociologist Bryan S. Turner argued that the tribal connotations of tattoos no longer existed and that tattoos were uniformly “commercial objects in a leisure marketplace and have become optional aspects of a body aesthetic.” In 2000, a team at Eastern Illinois University studied how tattoos had gone from “counterculture to campus,” surveying college students who had gotten them for reasons that they couldn’t articulate, and in contexts that had nothing to do with marginalization or rebellion. These students, the authors wrote, were getting tattoos “substantially free of class and ideology, much as any other commodity is purchased in a consumer culture.”

Then in 2009, University of Louisville sociologists Angela Orend and Patricia Gagné dug deeper into the idea of tattoos as commodities. The fastest-growing demographic for tattoos was white suburban women, making up half of the average tattoo parlor’s customers throughout the 1990s, and the study’s survey respondents overwhelmingly agreed that the popularity of tattoos had nearly eradicated their ability to shock.

“Still,” the authors added, “most held out hope that tattoos still held the potential to signify rebellion against the dominant culture, if one were willing to ‘take it to the next level’ by becoming heavily tattooed or getting tattoos on the face or neck.”

But 10 years later, that is normal too, thanks in part to that new class of ultra-popular rappers but more so to the platforms like Instagram and YouTube and SoundCloud, which promise success to young people only if they are instantly recognizable across the internet — only if they turn themselves into a commodity, and increasingly, in ways that are not reversible. (For Bieber, a tattoo may be more like an acknowledgment of the fact that his face has been for sale for a very long time, which is different, but not really.)

This commodification of the face sounds newly unreal, but it actually recalls a not-so-distant past: the dot-com boom.

That confusing, chaotic, wealthy time gave rise to the concept of “skinvertising” — a knee-buckingly sickening trend in which flash-in-the-pan internet companies looked for real estate for sale on people’s faces. And hands and arms and necks. In 2003, the London marketing agency Cunning Stunts Communications filed for a trademark on the term “ForeheADs.” (Now expired, if you’re looking.)

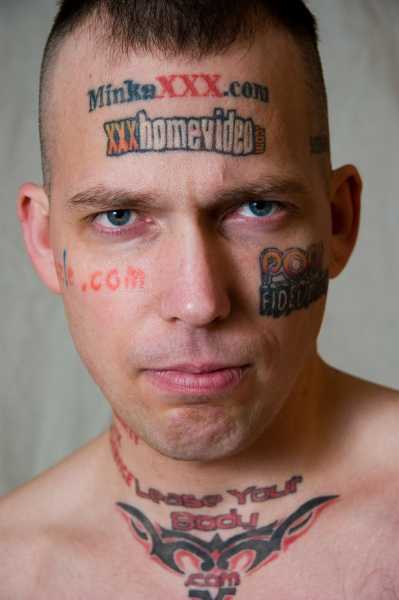

There are plenty of well-known examples: Karolyne Smith, a Utah woman, sold her entire forehead to an online gambling site called Golden Palace for $10,000 in 2005. An Alaskan man named Billy Gibby legally changed his name to Hostgator Dotcom (to promote the website HostGator.com) and has chunky block text tattoos for sites like DrFreak.com and XXXHomeVideo.com on his cheeks and forehead.

In a 2012 BuzzFeed feature, many of these people explained their choice to sell their faces, nearly all stating that they had been financially desperate. Now, for the most part, the websites that their bodies serve as ads for do not even exist.

The 2009 University of Louisville study also focused on tattoos of corporate logos, acquired for personal reasons and not to make quick cash. The authors were particularly surprised by people who explained their logo tattoos as signifiers of participation in specific “lifestyles,” and by the tattoo-havers’ tendency to say that they weren’t even thinking of the logos as “corporate symbols” at all. “Our findings on corporate logo tattoos provide strong support for the argument that tattoos are symbolic of the commodification of the body,” they wrote in the paper’s conclusion.

They go so far as to call their study subjects “human billboards.”

Though I don’t necessarily think tattoos on the faces of teen SoundCloud heroes are more tightly related to the horrible phenomenon of early aughts tat-vertising than they are to teardrop tattoos accumulated in prison, I don’t think they are any less related. Face ads were for money. Face tattoos — on YouTube, Instagram, or any platform that demands differentiation through shock and clickbait — are for attention, which is for money.

It might make sense for a musical artist to declare themselves a musical artist for life, to cover a small part of their face with a promise to their work; prototypical SoundCloud star Lil Uzi Vert told the Fader he got his hairline “Faith” tattoo so he would focus on his music, after holding a traditional job for four days and concluding that it was intolerable. But at the same time, the choice to bet your face on your music career, and your music career on the endurance of YouTube or Instagram doesn’t seem all that different from gambling the comprehensibility of your forehead slogan on the business model of a sketchy online ED drug reseller.

“More people know how to use Facebook, which was started in 2004, than natively speak any single language,” John Hermann wrote for the Awl in 2015, in a piece emphasizing the unbelievable clout of social platforms. He doesn’t point out, likely for brevity, that YouTube has more daily users even than Facebook, and that 300 hours of new video — more than the total run of M.*A*S*H — is uploaded to it every minute.

Face tattoos — on YouTube, Instagram, or any platform that demands differentiation through shock and clickbait — are for attention, which is for money

Our platforms are all-powerful, equipped with the might to make stars more famous than any previous generation of celebrities could fathom, and equipped to topple democracies. Day to day, they are able to steer young people into doing things that a handful of years ago would have seemed completely divorced from all logic or reward. Getting an exact copy of Rick Ross’s Miami Heat logo tattoo on your cheekbone would have mostly just confused your high school peers; there wouldn’t be a real chance of a record label caring. But Lil Pump was born in 2000, put his first single on SoundCloud in 2016, and got his first face tattoo in May 2017 and then his Warner Brothers deal in June, two months before his 17th birthday, just as he was hitting 6 million Instagram followers.

Hermann also points out that “a single person likely participates in sustaining many of these companies at once,” and that it isn’t always clear to them that they are doing so. As in, Facebook depends on Google and Apple to make phones that are amenable to its apps, and Google and Apple depend on platforms like Instagram and Snapchat to provide content that hold attention that breeds devotion to a phone. Google’s search and advertising businesses depended so much on low-cost video that it just went ahead and bought YouTube. You get the point. Each time we breathe life into one internet giant, we breathe life into the others. And each time we seek success on the internet, we have to seek it cross-platform.

The rules constantly shift, and the demands only swell. What good is your SoundCloud page without a rabid Twitter following? What good are your YouTube videos without Instagram Stories to tide your fans over? Who will watch them if they aren’t search engine optimized? It’s called a diversified revenue stream!

Of course, for a trend to be truly mainstream, it has to be adopted by people who are not famous and will never be famous, despite putting images of themselves all over the internet. That’s how we get to the face tattoos sported by midlevel vloggers on YouTube.

The face tattoos of YouTubers are their own thing, in that they are not about bolstering a music career. But they are also not their own thing, in that they so often reference the same knit-together set of internet-born celebrities. Face tattoos that made some amount of sense on the rappers situating themselves in the tradition of a specific art form, or pop stars declaring themselves at a certain level of unimpeachable status, are now making their way onto other faces, for vaguer reasons.

Vlogger Sagittarius Shawty for one, tells the camera, “Yesterday I realized I kind of don’t want to get this tattoo anymore. But I already paid for it, and, you know, I can’t get a refund.” She’s swaddled in a stained, baby pink Champion zip-up hoodie, her long purple hair pulled into two pigtails that sit directly on top of her head. “I don’t want to waste the money. So, YOLO.”

The nearly 14-minute video, which has close to 86,000 views, shows her putting in contacts and brushing what she calls her “pearly yellows,” before arriving at a tattoo parlor and asking, “Who’s ready to become a thug?” The tattoo she gets is a copy of the mumble rapper Lil Peep’s famous “Crybaby” scrawl, which covered the right half of his forehead and was mentioned in nearly every piece of writing about his meteoric rise on SoundCloud and entry into mainstream popular culture. He died in November 2017 of a Xanax and fentanyl overdose, but his posthumous album Come Over When You’re Sober, Pt 2. debuted at No. 4 on the Billboard 200.

Sagittarius is completely quiet while “Crybaby” is etched into her forehead, and then she’s completely quiet in the car, dabbing ink and blood off with a paper towel. The last minute of the video is dedicated to a reflection on the choices made in the previous 13 minutes, and she mutters, “I hope none of you are gonna go out and get a face tat,” then pauses. “It’ll look better when I wear makeup.” Pauses again. “I’m so stupid. Who the fuck does that? Sagi, Sagi, you poor little thing.” And finally, “I like it, I don’t care.” (She also has a broken heart on her cheek, maybe the most common choice among the SoundCloud crowd.)

In a different algorithmic aisle of the same site, Canadian Lael Hansen — who has nearly 700,000 subscribers on her highly produced, glossy-looking channel — is also getting her first face tattoo. Or rather, replaying for her audience an experience called “I GOT A FACE TATTOO (HUGE MISTAKE).”

Hansen has the round face, platinum-blonde hair, and blank eyes of a computer-generated avatar. She regularly cosplays as XXXTentacion, including styling her hair into an approximation of his dreads. Waffling about whether to get a tiny tree — identical to the one in the middle of XXXTentacion’s forehead — tattooed under her eye, Hansen ultimately shouts, “For the culture!” and runs off to do so.

While she talks, she alternates between pinching the air in front of her and dicing it like an onion, the familiar gestures of a self-help guru hosting a corporate seminar. “This is going to hold down, like, my position to do whatever the fuck I want,” she says. The tattoo artist is like, “Okay,” and appears to jab a leafless black tree into her face.

But her tattoo was temporary, as becomes obvious once you follow her on Instagram. It takes no effort at all to bounce between the fake and the real on the social web, and on the surface, everything looks exactly the same. Is Lael Hansen’s face more valuable with a tattoo or without a tattoo? How did she decide which one it was? We’ll never know, because she hasn’t replied to my emails.

What we do know is that the internet and the livelihoods that can be built off it are increasingly precarious and increasingly fabricated. I can easily see it both ways: It makes sense to get a real face tattoo, something that will guarantee you a viral hit and make you recognizable for as long as possible. It makes sense to get a fake face tattoo, something that good editing can dance around and that will rub off easily whenever YouTube and Instagram and everything else spin together down the drain. Lael Hansen is more cynical than Sagittarius Shawty, and knows it doesn’t matter what’s real. She’s also more of a human billboard than Sagittarius Shawty because her “face tattoo” exists only for marketing.

Unfortunately, I’m obsessed with YouTubers with face tattoos now. I watch Davine Jay, a prank YouTuber with 500,000 subscribers and the word “Pain” tattooed under his eye. I watch Tana Mongeau, who refers to herself as a “struggling demonetized influencer” and gets “11:11” tattooed on her temple. I watch British YouTuber Jack Francis, who has the same “Crybaby” tattoo as Sagittarius Shawty, and therefore Lil Peep, but, describing it, doesn’t even mention the late artist. “I got Crybaby here because, I dunno, I guess I’m an emotional person, I guess,” he says. “I kind of am a little bit of a crybaby.”

The last YouTube video I watch has more than 380,000 views and 3,000 comments. “You get the face tat, then you put out the music,” yells Bart Baker, a 32-year-old parody video YouTuber who has recently polled his viewers on whether he should launch a rap career. They said yes, so he is beholden to them, he explains. They also voted on what his rap name should be but he didn’t like what they chose, so he’ll instead go by Lil Kloroxxx.

“You get the face tat, then you put out the music”

He’s at the California Dream Tattoo, the shop in Los Angeles where celebrity tattoo artist Romeo Lacoste does his work. Lacoste has tattooed Ariana Grande and Kendrick Lamar, among others, and he has a sizable online following of his own — 1.9 million followers on Instagram, 1 million subscribers on his YouTube channel. Baker is understandably nervous to get his first tattoo, a strange experience even when it’s not on your face or of the word “Trap.” He yells virtually everything he says, then leans back and lets Lacoste do his thing.

“You’re a little red, but that’s normal, dude,” Lacoste tells him. “Just don’t regret it.”

Afterward, Baker is extremely excited, and emerges from the parlor with his new tattoo gleaming under Vaseline just inside the frame of his Jeffrey Dahmer glasses. “Who’s living the life?” he shouts, as a young boy, a younger girl, and their mother run across the parking lot for a hug and a photo with him.

One night, weeks after I watch this video, still several more weeks before I will fully recuperate from it, I call Lacoste to ask how much face tattoos cost and how often he does them and how exactly he feels about having tattooed the word “Trap” on a person named Bart Baker’s face. “I’m not really a big fan,” he says. “Your face is your identity. You shouldn’t mess with your face.” (His minimum rate is $500.)

Then he tells me he’s not sure if Baker is serious about being a rapper. I’ll admit that despite the fact that he has launched a Spotify artist page and has a few songs posted on YouTube, I can’t really tell either. The songs are terrible, but this would be far from the first time someone seriously endeavored to do something they were bad at.

“It’s kinda funny, but that tattoo isn’t real,” Lacoste tells me, almost as an afterthought. “I don’t know if I’m supposed to say that. It’s a stencil he puts on for his persona.” I ask him if he was annoyed by the request to fake a tattoo, given that he’s a real tattoo artist who gives real tattoos for a living.

“A lot of YouTube is fake,” Lacoste says. “It’s for entertainment. It’s not a big deal.”

Want more stories from The Goods by Vox? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Sourse: vox.com