Flickr, the photo storage website that had, at its peak, close to 90 million users, is disintegrating, and it’s taking 15 years of internet history with it.

The company, which has been financially troubled for some time and was sold by Yahoo to photo-hosting service SmugMug in April 2018, will discontinue its free terabyte of storage for all users and started deleting files from accounts that exceed the new cap of 1,000 photos, starting March 12 (the deadline has been extended following outcry from users). Now, free Flickr accounts are, if anything, one extra filing cabinet. They’ll bear almost no resemblance to the entire basements they once were.

This fact may be largely undisturbing to you if you never used the platform to store a significant amount of your photos. But if you care about the history of the culture of the internet and the forces that are shaping its future, you should note this moment as an important one.

What does deleting millions of photos mean for the history of the internet? In some ways, it doesn’t mean much. These are, after all, photos that users didn’t bother to download in the three-month warning period that SmugMug gave them.

You could argue that they are things nobody cares about, the type of detritus that is lost all the time, everywhere, for lots of reasons. You could also argue that there might have come a day when we wanted them. For the New York Times last November, tech columnist John Hermann labeled the problem of digital photo storage “the great unsolved tech support question of the last 30 years,” and asked, “Do you know where your photos are?” At the very least, this an occasion to think more seriously about the precarity of all images entrusted to free services or erodible devices.

Before we freak out: A lot of the important stuff is already being saved.

Mario Klingemann, a digital artist and archivist based in Germany, tells Vox that he wasn’t surprised when Flickr announced the end of its free terabyte in November. “Of course, anything on the internet that is free is kind of … probably not forever.”

Noting that the photos that fall under a free, Creative Commons fair-use license are safe — both by Flickr’s promise and because the Internet Archive is busily making duplicates — he says, “I’m not totally in tears because the most relevant stuff will still be available. But the beauty of this abundance of data is the process of discovery and finding the golden nuggets in this huge desert of non-relevant information.”

“In the end, probably not many people will notice what is lost, because we didn’t know what was there.” Klingemann says, getting a little bit sad after all. “It’s not comforting, it’s just simply a fact. There’s so much data now, you’ll find something else. If you haven’t found it by now and kept it safe, you will probably never know.”

“In the end, probably not many people will notice what is lost, because we didn’t know what was there”

This is not unique to the internet, though, he argues. Memorabilia has always been lost to time or poor storage. We have warehouses full of forgotten items, museum basements, physical spaces that are not unlike digital photo collections in their general uselessness — “In a sense, something only exists when somebody comes along and finds it, in a certain time, with a certain search in mind.”

But Matt Schimkowitz, an editor at the internet culture database Know Your Meme, tells Vox that this content was being used. “In general, it’s never great when a vast trove of online content is taken down,” he writes. “Flickr, at least for our purposes, has become something of a time capsule for late-2000s internet — one that has helped us document many cultural trends of the mid-to-late aughts.” He hopes some of the images will be archived somewhere else, but says, “More likely, [they’ll] be lost either because people don’t remember their Flickr password, don’t want their pictures online anymore, or simply don’t hear about the shutdown.”

Big chunks of our online cultural history is disappearing, and there’s one company to put a lot of blame on

Flickr was founded in 2004 by Slack co-founder Stewart Butterfield and serial tech entrepreneur Caterina Fake, then acquired by Yahoo in 2005. In 2007, Yahoo discontinued its own photo service and compelled all of those users to move over to Flickr or lose their data. In 2013 (the same year that Yahoo bought Tumblr), the company announced that all users would get a free terabyte of storage on the platform — more space than your average person could really imagine using — and that Pro accounts would be more expensive and offer virtually unlimited storage. Verizon bought AOL in 2015, then Yahoo in 2017, merging the two to form a media company called Oath, which then sold Flickr to SmugMug. SmugMug announced the end of the free terabyte in November 2018, encouraging users to upgrade or back up their files.

When we talk about the loss of internet culture, a lot of roads lead back to Yahoo

When we talk about the loss of internet culture, a lot of roads lead back to Yahoo. Or more generally, to acquisitions and consolidations in the tech sphere that come with streamlining — not just the winnowing down of valuations and the loss of jobs, but the ditching of troves of images, videos, and text that go unclaimed when email address-based user accounts change hands and get lost.

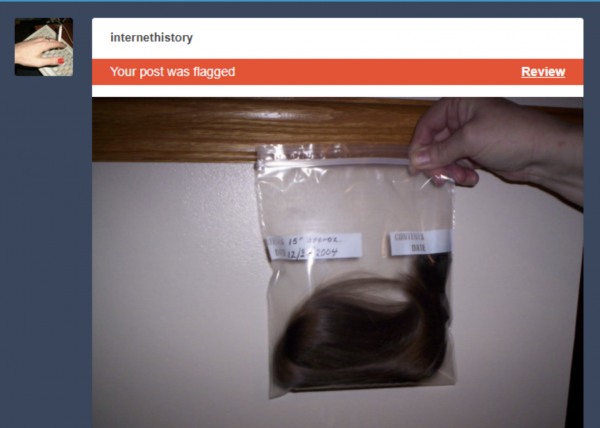

BuzzFeed’s Katie Notopoulos predicted the erosion of the history of the web in 2012 when she wrote about the demise of photo-hosting service Webshots. A much smaller site than Flickr, Webshots held about 690 million photos at the time (Flickr had more than 6 billion at the same point). Many of the photos that were lost were strange, eerie, and decidedly mid-2000’s, and important enough for self-proclaimed internet history archivist Doug Battenhausen to rip onto a Tumblr.

His account is still there, but it is covered with takedown notices triggered by Tumblr’s new NSFW content bans and laughable ability to implement them evenly. Those bans only happened because Yahoo floundered and put the site at the mercy of Verizon, which wanted it only for ad revenue and wouldn’t put resources into better moderation algorithms or more staff.

“Who knows what Instagram or Twitter or Facebook will be like in seven years, or in 15 years,” Notopoulos wrote in 2012, “It’s not a stretch to imagine a day when all our words and images hosted on these services are removed [as] the companies collapse or morph.”

In December 2018, when Tumblr enacted its sweeping porn ban, she followed up, writing, “This is not the beginning of the end of the internet as we know it. That began years ago, maybe starting with Yahoo’s deletion of Geocities in 2009[.]”

It’s not all Yahoo’s fault, but a lot of it is Yahoo’s fault. (In 2012, Mat Honan wrote at Gizmodo that Yahoo had “killed Flickr and lost the internet,” a bold statement that didn’t seem untrue when he said it, but appears emphatically more true now.)

Don’t be mad at Flickr. Do think about paying for photo storage if it’s really important to you.

Jason Scott, an archivist at the Internet Archive, tells Vox, “In its current form, Flickr was unsustainable. There is not a single person who knows anything who would say differently.”

He puts no blame on the new owners, arguing that they were transparent about their business concerns and spoke “extensively with the community, and everybody who reached out them, even the furious ones.” Flickr’s Creative Commons imagery will remain online, as will government items and many images posted by nonprofits and museums. Scott says he personally suggested that the company allow people to gift each other Pro accounts, and they set it up as an option six days later. The Internet Archive is duplicating as much as it can, based on requests.

“We have apparently been training a generation of computer users that they don’t have to pay for anything”

“They are listening, but it will still be a disaster,” Scott says, not because of anything Flickr specifically has done but because, “We have apparently been training a generation of computer users that they don’t have to pay for anything.”

Richard Ovenden, head of the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, echoes Scott, telling Vox in a phone call that Flickr’s demise is “a sign of the constantly shifting fortunes of the big tech players.” He adds, “To me, what it really means is that although these services are free to any users, it doesn’t mean that they don’t cost anything to run. It’s a reminder that archival activity is costly.”

Things will get lost, including a big chunk of internet history. But Ovenden says the more important shift to notice is the shift, again, “towards the very largest players who can, at the moment, continue to afford to offer unlimited storage.” Of course, these much bigger companies can afford to offer that kind of free service only because they’ve figured out how to monetize their users in other ways: tracking our behavior, selling ads against us, collecting billions of user profiles.

“Flickr is just not in that category,” Ovenden says. “Free storage services are nearing the end of their lifespan.” He predicts that people who don’t want to turn all of their photos over to Facebook or Google will have to cough up some real money now, and that paid-for services may come “back into fashion.”

This piece has been updated to reflect the extended deadline of March 12.

Sourse: vox.com