relatives in Chinese internment camps” alt=”"Are they alive?": Uighur Muslims demand videos of relatives in Chinese internment camps” />

relatives in Chinese internment camps” alt=”"Are they alive?": Uighur Muslims demand videos of relatives in Chinese internment camps” />

“Are they alive?”: Uighur Muslims demand videos of relatives in Chinese internment camps

How a “proof of life” video backfired on Beijing.

By

Sigal Samuel

Feb 12, 2019, 1:40pm EST

Share

Tweet

Share

Share

“Are they alive?”: Uighur Muslims demand videos of relatives in Chinese internment camps

tweet

share

Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

China accidentally opened a can of worms when it released a video this weekend purporting to prove that an imprisoned Uighur musician was alive and well, contrary to recent reports that he’d died in Chinese custody. But the tactic backfired — within hours, Uighurs around the world took to social media to post pictures of their loved ones believed to be in Chinese internment camps. They demanded that China post “proof of life” videos for them, too.

It was the latest surprising turn in a story that has been largely neglected by the US public, but looms as one of the most pressing humanitarian crises in the world today. Since 2017, China has been rounding up Uighur Muslims and detaining them without trial in a massive network of internment camps, which currently hold an estimated 1 million people.

The online firestorm started when Turkey released an unusually strong statement on Saturday slamming China for its mass incarceration of Uighurs, and specifically mentioning the famous musician, Abdurehim Heyit, who was rumored to have died in the second year of an eight-year prison sentence over one of his songs.

China countered by releasing the video purportedly showing a healthy Heyit and blasted Turkey for spreading “absurd lies.” Experts immediately cast doubt on the authenticity of the video, though, saying it was probably coerced out of Heyit, digitally doctored, or both.

Keen not to let Beijing get away with using technology to repress vulnerable citizens, Uighur activists around the world bent technology to their own ends. On Monday, they started a social media campaign under the hashtag #MeTooUyghur. It invited Uighurs with relatives in the camps to demand that China release videos of their family members.

Murat Harri Uyghur, a doctor who moved to Finland in 2010, is the mastermind behind #MeTooUyghur. He told me he thought up the idea because he felt Turkey and China were in a game of “hot potato,” each parrying the other’s moves. “I discussed this with one of my friends — how can we throw it back to China?” he said. “They released a video to show Heyit is still alive. So, hey, there’s another million detainees — are they still alive? Make a video of them!”

For Uighurs, Turkey’s statement registered as a major inflection point in the international response to the repression. Most Muslim-majority countries have been silent about the Uighurs’ fate, likely fearing economic or political backlash from China, a country often viewed as too influential to anger. Turkey kept quiet even though its president has often styled himself as the moral leader of the Muslim world, and even though the country is home to a significant Uighur population.

Now, its decision to speak up could signal a sea change for this high-impact but internationally neglected human rights crisis. “The reintroduction of internment camps in the XXIst century and the policy of systematic assimilation against the Uighur Turks carried out by the authorities of China is a great shame for humanity,” said the Turkish Foreign Ministry in its statement, calling on Beijing to close the camps.

Prompted by such words and by the #MeTooUyghur campaign, other countries may be emboldened to demand an end to what the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China has called “the largest mass incarceration of a minority population in the world today.”

Who are the Uighurs and why are they being detained?

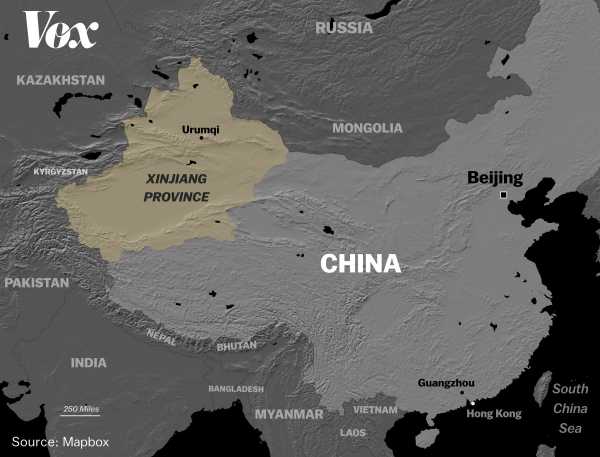

Uighurs are a mostly Muslim ethnic minority concentrated in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region. They speak a Turkic language and some of them want Xinjiang, which they call East Turkestan, to achieve independence from China. Beijing fears this separatist impulse, especially now that it’s rolling out its Belt and Road Initiative, a sprawling infrastructure project for which the oil- and resource-rich Xinjiang region is crucial.

After ethnic riots there killed hundreds in 2009, and especially after the September 11 attacks made “Islamic extremism” a commonly invoked specter worldwide, China has been painting the Uighur people as a major terrorist threat. Although it’s true that some radical Uighurs have perpetrated terror attacks, China’s approach — which targets a vast swath of the Uighur population — has been clearly disproportionate.

The mass internment system China kicked off in 2017 was developed with the purpose of “de-extremifying” Uighurs. Even the most harmless signs of Muslim identity, like a long beard, can be considered a sign of extremism and get someone sent to an internment camp for forced indoctrination. As I’ve reported for the Atlantic, Chinese officials have likened Islam to a mental illness and characterized indoctrination as “a free hospital treatment for the masses with sick thinking.”

Over the past year, extremely disturbing information has surfaced about what happens to Uighurs in the camps. There have been reports of death, of torture, of Muslim detainees being forced to memorize Chinese Communist Party propaganda, renounce Islam, and consume pork and alcohol.

At first, Beijing flat-out denied the existence of indoctrination camps, claiming that they’re just vocational schools for criminals. But journalists, researchers, and activists showed not only that indoctrination camps exist but that, as Vox’s Alexia Fernández Campbell wrote, “these centers have a lot more in common with concentration camps,” especially considering the “disturbing purchases made by government agencies that oversee the so-called education centers: 2,768 police batons, 550 electric cattle prods, 1,367 pairs of handcuffs, and 2,792 cans of pepper spray.”

In late 2018, China faced blistering condemnation from the United Nations, watchdog groups like Human Rights Watch, and Western countries like the US and Canada. A couple of Muslim-majority countries, Malaysia and Indonesia, joined in the criticism. Beijing was forced to change tack: It acknowledged that it was detaining Uighurs for “de-extremification” but tried to retroactively legalize the move and even painted the camps as fun, resort-like places.

Almost nobody in the international arena bought that story, but so far the outcry hasn’t been enough to prompt China to change its policies.

Some Uighur activists are hopeful, though, that a bold new statement like Turkey’s could help. “If Turkey continues its efforts to raise these issues at higher levels, it can bring about real changes,” Tahir Imin, a US-based Uighur academic, told me. (However, Turkey may not be the most credible voice when it comes to human rights, given the way it’s suppressed journalists and other dissenting voices at home.)

As far as Turkey’s motivations for speaking up now, some experts believe the reports of Heyit’s death were “the drop in the bucket that caused the bucket to overflow,” as prominent China researcher Adrian Zenz described it to the New York Times.

But Turkey could conceivably have motivations other than standing up for Muslims. Uyghur, the creator of #MeTooUyghur, told me he believes the ruling AKP Party was trying to appeal to voters. “The Turkish government doesn’t want to lose the upcoming election,” he said, referring to the local elections that will be held in March. After the death of Heyit, he added, “they’re receiving too much pressure from their public, so they had to make a statement.”

How China uses tech for repression — and how tech can counter it

Practically every day, a new headline appears warning in apocalyptic tones about China’s development of new technologies. The country has a penchant for using tech to solve problems ranging from the trivial (people who jaywalk or who use too much toilet paper) to the serious (criminals who try to avoid detection in crowds).

But Beijing was wildly mistaken if it hoped the video purporting to show Heyit in good health, which was uploaded to state-run China Radio International on Sunday, would quash rumors of the musician’s death. Instead, China experts and academics are pointing out that the video can’t be taken at face value. The Chinese Communist Party is well known for extracting and televising forced video confessions. It’s possible that China coerced the musician into giving voice to scripted words. It’s also possible that the video was doctored.

“The Chinese government has long used the tactic of videotaping activists and other captives and releasing footage of them as a means to deflect international criticism about reports of their mistreatment,” Maya Wang, a senior researcher on China at Human Rights Watch, told me by email. “Abdurehim Heyit’s video is no exception. If anything, the video proves only one thing: that the Chinese government has finally admitted to forcibly disappearing Abdurehim Heyit. There is no information about what crime he might be charged with — or that he has been charged at all — where he is held, what kind of procedure he has been subjected to, whether he has access to lawyers, or his true well-being.”

Imin, who has spent time in a Chinese prison, told me he was skeptical of the video for many reasons, including the fact that it showed Heyit “dressed in his own normal clothes” rather than in the uniform that would be standard fare for someone under investigation. “It’s a kind of show. The Chinese government wants to show the world that he’s being investigated like in a normal process.”

On Twitter, some Uighur advocates have already dug through the video’s metadata. “The anomaly I’ve noticed is that, according to the video metadata, video duration is 25 s 840 ms and audio duration is 25 s 922 ms,” wrote Otkur Arslan. “Usually they should be the same lengths, so it might suggest a possible tempering of the video or audio.” Zenz, the researcher, added that the length discrepancy “might explain an edit that may have removed something that Heyit had said.”

Others wondered online whether this video might be a deepfake, a new AI-enabled technology that, as my colleague Brian Resnick has explained, makes it disturbingly easy (and free) to “convincingly map anyone’s face onto the body of another person in a video.”

For now these are unverified hypotheses, and there is no evidence proving that China doctored or manufactured the video. But the fact that observers immediately began floating such ideas is a testament to the rampant anxiety about how China — which has been much more proactive about AI development than the US has — may be abusing new technologies in the service of abusing vast numbers of human beings.

The silver lining is that even as China has used cutting-edge surveillance and propaganda technologies to repress minorities, people around the world have successfully been using simpler tech to pull back the veil on the country’s mass internment system. As I reported for the Atlantic last year, Uighur activists, journalists, and researchers around the world have been using digital tools like the Wayback Machine and Google Earth to find and disseminate information about the camps.

The quest to hold China to account has been uniting online activists in this collaborative global effort for a while now. The work of web sleuths poring over the Heyit video and the #MeTooUyghur social media campaign are the newest examples.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Sourse: vox.com