Over 100 players from a diverse background have played for the England men’s and women’s senior teams.

Viv Anderson was the first Black player to earn a senior cap in 1978. Luther Blissett was the first Black player to score in a Three Lions shirt. John Barnes was the first Black player to play in a World Cup for England. Paul Ince was the nation’s first Black captain. Ashley Cole was the first Black player to earn 100 England caps.

But there has only ever been one Black goalkeeper: David James.

The 52-year-old – born to a Jamaican father and English mother – played over 1,000 professional games during a 26-year professional career and, after his debut in 1997, appeared 53 times for England.

For the documentary David James: The One & Only, Sky Sports followed James as he spoke to more than 25 in an attempt to find out why no one has followed in his footsteps.

Trending

- Transfer Centre LIVE! Real exploring move for Mbappe alongside Bellingham

- Papers: Arsenal fear being priced out of £100m Rice deal

- Man Utd transfer rumours: ‘Glazers name Ratcliffe preferred bidder’

- Hits and misses: Did VAR take pity on AC Milan?

- Why have England only ever had one Black senior ‘keeper?

- Moyes: ECL final with West Ham could be my best career achievement

- Ricciardo aims to remind Red Bull ‘I can still do it’ in July RB19 drive

- Liverpool transfers: Reds make move on Mac Allister

- Ismael appointed Watford head coach | 19th manager of Pozzo reign

- Hayes revelling in Man Utd chase: ‘I like putting pressure on others’

- Video

- Latest News

David James: The One and Only

Sunday 14th May 7:30pm

A history of Black goalkeepers in England

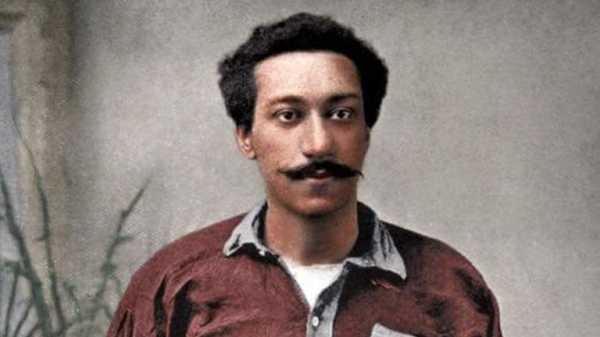

Arthur Wharton was the beginning of the Black presence in football. A man of many sporting talents, he was the first Black professional footballer; a goalkeeper who also played on the wing.

Image: Arthur Wharton was the first Black professional footballer

“He would hang on the crossbar and catch the ball between his legs. He would crouch in the corner, get onrushing forwards to take a shot, then he’d dive and save it,” says Shaun Campbell of the Arthur Wharton Foundation.

Also See:

“But the colour of his skin prevented him from playing for England.”

Image: A statue of Wharton was unveiled at St George's Park in 2014

Wharton died in 1930 and it was not until Derek Richardson started his career at Chelsea in the mid-1970s that there was another Black English goalkeeper.

In 1979, the 66-year-old – who later turned out for QPR, Sheffield United and Coventry – played in West Brom legend Len Cantello’s testimonial – the highly controversial Blacks vs Whites match.

“I jumped on the invitation as West Brom had some great Black players,” says Richardson, a black cab driver for the majority of his post-football life, whom Sky Sports News tracked down through contacting his family.

“We won 3-2, but we didn’t think the score was important. It became apparent that the score was important because, outside the ground, the National Front were handing out leaflets. I, maybe, gave the underprivileged hope.”

Image: Derek Richardson played in the infamous Blacks vs Whites match in 1979

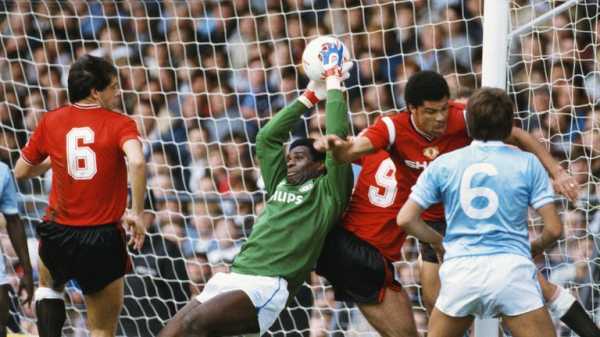

James’ icon growing up was Manchester City No 1 Alex Williams.

“Through the junior football scene, I didn’t really have any racism at all because, as a kid, most people thought, ‘He’s a young Black goalkeeper, he’s obviously not going to go anywhere,'” Williams explains.

“It was only a little bit later when I started to progress seriously in professional football that I started to see and hear different things. I had to be strong-willed.

“It made me play better, so certainly in the early part of my career, I won a lot of people over because of my performances and people started to see me as a good goalkeeper, rather than a Black goalkeeper, which was important to me.”

He was part of the England U21 squad that won the Euros in 1984, but how close was he to playing for the senior team?

Image: Alex Williams was Manchester City's first-choice goalkeeper during the 1983/84 and 1984/85 campaigns

“I’d like to think, if I’d progressed, I’d have been on the fringes, but we had world-class goalkeepers in those days: Ray Clemence, Joe Corrigan, Peter Shilton. Even to be associated with them was fantastic.”

The closest any Black male goalkeeper has come to following in James’ footsteps was when Shaka Hislop made the bench for England’s match against Chile at Wembley in February 1998. One year later, he made the first of 26 caps for Trinidad & Tobago.

Shaka Hislop appeared once on the bench for England before playing senior international football for Trinidad & Tobago

Does he ever wish he’d played for England?

“I’ve learned not to live with regret around decisions I’ve made. At the time, it was the right decision, that’s how I felt. I felt that was what I wanted to do, what I’d always dreamed of doing.

“Sure, I can look back now and wonder what if? My stock would have been a lot higher if I’d have represented England, but I still maintain that representing Trindad & Tobago in our first World Cup appearance in 2006 was easily the highlight of my professional career.”

Image: Shaka Hislop featured on the bench for England in 1998 and then faced them as Trindad & Tobago 'keeper in the World Cup eight years later

While no-one has come closer than Hislop, Lee Grant played for the U21s, as did Matt Murray. The latter – whose career was cut short by injury – was aware of discrimination from an early age.

“Unfortunately, I found out very early that I was different to the other kids,” he says. “From a very young age, there were obstacles.

Image: Matt Murray earned five England U21 caps between 2003 and 2005

“I’ll always remember my first game, when I was nine. I slid out, got a ball, the striker ran over me, penalty. When do you give a penalty against a nine-year-old? And for lying on the ball and someone running over you? I know to this day why that penalty was given.

Matt Murray: “There were times where I went home and cried. Now, I’m so proud of my colour, my journey and my story”

“I always felt I didn’t have to be as good, I had to be better. There were times where I went home and cried. Now, I’m so proud of my colour, my journey and my story.

“In terms of England, I know there was talk of me getting called up and Ray Clemence was coming to watch me. But the obstacles, I do believe, were my injuries. To play for England, you have to be super robust.”

Representation improving in the English game

At QPR, Seny Dieng is a Senegalese international, Jordan Archer was Scotland’s first Black goalkeeper, and Matteo Salamon is an up-and-coming stopper born in Brazil and raised in London.

Image: Seny Dieng has made over 100 league appearances for QPR

Josh Oluwayemi, 22 – brother of Celtic ‘keeper Tobi – has made four league appearances for Portsmouth and, while he has played for England at U15 and U16 level, just under two years ago, he was called up to the senior Nigeria squad, though he was not capped.

Lawrence Vigouroux is at Leyton Orient, Jamal Blackman – formerly of England U16, U17 and U19 – is at Exeter.

Brentford goalkeeper Ellery Balcombe, 23, played for England at U18, U19 and U20 level.

“I’ve heard the stereotype that you can’t trust a Black goalkeeper,” Balcombe says. “I’ve always been out to prove a point that you can.”

Did he ever think his colour would stop him playing for his country?

Image: Ellery Balcombe spent the second half of 2022/23 on loan at Bristol Rovers

“A little bit, yes. Before I was in the camps, I was seeing the goalkeepers in there whose backgrounds are completely different to mine. I thought I was way better than them, why wasn’t I getting the opportunities? But it was just because England hadn’t seen me at that point.

“More people from different minorities are wanting to become goalkeepers these days. I feel like history is only going to push us on to get more people from different backgrounds into the game.”

Sheffield United’s Wes Foderingham agrees.

Image: Wes Foderingham is one of the most experienced goalkeepers in the EFL, having made close to 500 senior appearances

“There’s always been that stigma around Black goalkeepers that they are somewhat untrustworthy. I’m not sure why that is, but I felt that growing up,” the former England U16, U17 and U19 international explained.

“I’d go somewhere and people would say, ‘Oh you play football – are you a winger?’ I’d say I’m a goalkeeper and there’d be a look on their face – that doesn’t happen with a white goalkeeper.

“The main thing for me is that, if you have a young Black kid who wants to play in goal, he doesn’t feel like he can’t because he’s Black. You never want to get to a position where we say we need to have more Black goalkeepers for the sake of it.”

Wes Foderingham: “You never want to get to a position where we say we need to have more Black goalkeepers for the sake of it”

Birmingham’s Neil Etheridge appeared once for England’s U16s in 2005, before declaring for the Philippines, the country of his mother.

“I made the decision to play for my national team when I was 18. At the time, I was in and out of the England setup and when I went to train with the Philippines, I fell in love with it. I’m very proud to be Filipino.

“To be the first South East Asian player to play in the Premier League didn’t sink in for a long, long time. There are many other goalkeepers who have got serious amounts of talent in South East Asia and in Asia who’ve decided not to come here.

“There is a stigma about them; they’re not as good, they’re not as agile, they’re too agile, they’re too quick, they’re not solid enough, they make too many mistakes.

Image: Neil Etheridge was the first South East Asian to play in the Premier League

“If we’re talking about race, don’t British goalkeepers do exactly the same? Don’t English goalkeepers do the same? Don’t white goalkeepers do the same? Either you like someone or you don’t. It shouldn’t come down to race.”

West Brom’s teenage goalkeeper Ben Cisse – an England U18 player – puts a positive spin on it.

“I feel like everyone is given a fair opportunity, especially me at this club. If I’ve worked hard and they believe I can thrive, they’ve always given me the right opportunity to succeed. You play your best because at the end of the day, you’re only going to get picked on how you play, not because of your skin colour.

“I feel like all Black ‘keepers are able to become the next England goalkeeper, it’s about the right opportunities that they get at their clubs.

“I feel like now there’s more interest, there’s new things evolving with ‘keepers being able to play with their feet. It becomes like a risk-taking job in which people might find interest. In my games, I try to emulate what players do in the biggest leagues in order to show that I’m capable of doing what they can do.”

The global landscape

The lack of diverse goalkeepers is not an issue exclusive to England. Far from it, in fact.

Take players with African citizenship, for example. Of those who currently play in Europe’s top five leagues, just 3.52 per cent are goalkeepers, which is a startling figure in comparison to defenders (32.04 per cent), midfielders (29.23 per cent) and attackers (35.21 per cent).

Datawrapper Due to your consent preferences, you’re not able to view this. Open Privacy Options

Many of those who have made it through in the past have left a legacy, including former Cameroon goalkeeper and current Espanyol coach Thomas N’Kono, whom legendary Italian stopper Gianluigi Buffon credits as his idol growing up.

Italy legend Gianluigi Buffon explains why Cameroonian goalkeeper Thomas N’Kono was his idol growing up

“In 1982, I profited from the World Cup being in Spain and that allowed me to get to know people around the world,” N’Kono explains.

“It meant that everyone discovered I was equipped and had the skills to be able to be professional. But when I arrived in Spain, I had the position of being a foreigner, so it was much more difficult to establish myself as a professional at a club and to get the opportunity to play in Spain.

“Today, it’s a lot easier, but I think we could do better. If African goalkeeper coaches were already better trained, I believe there would be a lot more [Black goalkeepers]. Everything that comes after will be a bonus because many of these young goalkeepers who want to learn can be fine-tuned to succeed in Africa.”

Before Dida started in goal against Croatia in Brazil’s opening match of the 2006 World Cup, no Black goalkeeper had played for the nation on the world stage in 56 years.

Heurelho Gomes discusses the story of Moacir Barbosa and why, after 1950, it took more than a half-a-century for a Black Brazilian goalkeeper to play at a World Cup

His predecessor was Moacir Barbosa, who was treated as an outcast after his mistake in the 1950 final allowed Uruguay to triumph 2-1 in front of a crowd of 173,000 at the Maracana.

“Of course, there was some kind of racism there,” says ex-Tottenham and Watford goalkeeper Heurelho Gomes. “But the people pointed the finger to him more because of his mistake than him being a Black goalkeeper.

“I never heard in Brazil that I was not going to play because I was Black. I never heard you are not going to play in goal because Barbosa made a mistake in 1950. If you have the ability, nobody can stop you.”

Elsewhere, Southampton’s Gavin Bazunu – born to an Irish mum and Nigerian dad – plays for the Republic of Ireland and has 14 senior caps to his name already, despite having only turned 21 in February.

“My mum is Irish and my dad is from Nigeria,” he said. “I’m very proud of my Nigerian heritage and that side of my family.

Image: Southampton's Gavin Bazunu says his source of inspiration growing up was Darren Randolph

“When I started to break in, Darren Randolph was one of the goalkeepers I was looking up to at the time. The biggest motivation he gave me was to see somebody like me playing for Ireland and it really felt achievable. To be able to see somebody who has come before you allows you to reach your goals.”

Sevilla’s Moroccan goalkeeper Bono – who starred in his nation’s incredible run to the 2022 World Cup semi-finals, becoming the first African goalkeeper to keep three clean sheets at a single edition of the tournament – wants to use his platform for good.

Morocco’s Bono feels responsible for changing attitudes to make things easier for goalkeepers of the future

“The World Cup changed our lives,” he says. “The African goalkeeper of the future will be better for sure because other goalkeepers before opened the door. I have the responsibility to change the mentality.”

The women’s game

The USA Women’s World Cup-winning squad in 1999 featured two Black goalkeepers: Briana Scurry and Saskia Webber.

The former earned 175 caps during a 14-year international career and saved the penalty that secured glory for the American team against China. The latter says her colleague did not receive the plaudits her heroics deserved.

Image: Briana Scurry's crucial penalty save against China won the World Cup for the USA in 1999

“More of the discrimination in the sport was from the outside. Bri and I have talked about this; she did not get the recognition. She was forgotten about,” insists Webber.

“Was it because – we’ll be blunt and honest – she’s dark-skinned Black, at that time not marketable? I’ll call everybody out right now because that is what it was. She didn’t get the endorsements. She didn’t make the money. She was overlooked – and there’s only one reason for that.”

Saskia Webber on the lack of recognition her international team-mate Briana Scurry received after her crucial shootout save won the 1999 World Cup for the USA

Aman Dosanj became the first British South Asian to play for England at any level when she represented the U16s in 1999, garnering comparisons to Parminder Nagra’s role of Jess in the 2002 film ‘Bend it like Beckham’.

“I don’t think as a kid you’re ever aware of the historical significance,” she says, speaking from Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada, where she now works as a chef. “I was just a kid who started play football because my brother wanted a brother, and he got me instead.

Image: Aman Dosanj (right) was the first British South Asian to play for England at any level, with her story drawing comparisons to Parminder Nagra's (left) character in the film 'Bend it like Beckham'

“When I was playing for England, I was second choice. My back line knew that my hands were safe. And they trusted me more, so they even came up to me and said that, too.

“I was leaner, I was a lot more agile. It wasn’t necessarily saying that I was not worthy in the sense of making the mistakes and stuff like that, it was more it being my height being the issue.”

Tottenham’s Becky Spencer, meanwhile, played for England at U19 and U20 level and was an unused sub for the senior team for a match against Estonia in 2016.

Negative attitudes towards her, she says, proved a deciding factor in declaring her international allegiance to Jamaica, for whom she earned the first of four caps in June 2021.

Image: Tottenham's Becky Spencer earned her first cap for Jamaica in 2016

“When I was in the Arsenal team, there were a lot of Black players,” she says. “I was in that environment, so I didn’t realise what a massive gap there was with the lack of Black goalkeepers. I’ve been in the WSL now for over 10 years and I’ve been one of the only ones for that period. It concerns me because I don’t know why.

“I was too laid back for certain managers, my body shape wasn’t the right fit for what they wanted, I needed to lose weight. There were all sorts of different things against me that I had to keep fighting against.

“Some of my best memories were playing for England U19s, but then was a shift between me going from the U19s to the seniors.

Negative attitudes towards Tottenham’s Becky Spencer led to her declaring her international allegiance to Jamaica

“There was a Euros that I got left out of and I didn’t know why; I was playing for Chelsea and playing well. The reasoning I got was that I hadn’t done anything in my career – and this was off the back of winning every single thing I could in domestic football. That made it such an easy decision for me to go and play for Jamaica.

“A lot of parents of Black players in academy football have messaged me on Instagram, enquiring about playing for Jamaica because they don’t see a pathway for their children in the England setup as they are seeing squad pictures without any Black players involved at all.”

In response to Spencer, an FA spokesperson said: “We have publicly committed to improving the diversity within our England pathway but also within the wider game as a whole. That includes working with Government so every girl can have the chance to play in school.

“We have also completely restructured our talent pathway so more young girls from all backgrounds can find a local place to play and we are then ensuring it is possible for the very best talent to be identified. Of course, while progress is being made, there is always more to do.”

Image: Kay Cossington (first on the right) is women's technical director at the FA

That follows on from FA women’s technical director Kay Cossington’s statement in February after a new look Women’s and Girls’ Player Pathway was launched.

She said: “We want to ensure we can reach every community in this country and allow every young girl that wants to fulfil the dream of being a professional footballer or playing for England has the opportunity to do so.”

That commitment is already showing signs of success. The number of Black, Asian and Mixed Heritage players selected for Women’s U17 camps increased from five per cent in August 2019 to 40 per cent in March 2023.

In the latest U17 camp, eight of the 20 players selected from from a Black, Asian or Mixed Heritage background, with family connections including India, Japan, Singapore, Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda, Guyana, Jamaica and Monserrat.

Ex-Arsenal and Tottenham stopper Chloe Morgan, who retired last year, owns a goalkeeping coaching company and says she has noticed a lack of diversity in the players who sign up to take part in camps she organises.

Ex-Arsenal and Tottenham goalkeeper Chloe Morgan says changes need to be made now to ensure there is a more diverse women’s footballing landscape in the future

“What I’ve seen is the majority of the goalkeepers who sign onto the sessions are white. The fact that we’re getting girl goalkeepers coming to these sessions in such large quantities at all is incredible, but I really had to think about why there weren’t more mixed race, Asian, Black young goalkeepers out there.

“Off the back of the Black Lives Matter movement, people’s awareness of racial issues, tension and even the LGBTQ+ community and gender, there was a big period of reflection, looking at policies and practices, saying, ‘Can we do things better?’

“Are we reaching the most girls we can to say representation isn’t great, but we want to make sure you’re included going forward and we want to see a more diverse women’s footballing landscape in the future? To have that, we need to start making changes now.”

Manchester City’s rising star between the sticks, Khiara Keating, however, suggests the landscape is already changing.

The 18-year-old spent the second half of the season on loan at Coventry United in the FA Women’s Championship and has earned nine caps for England’s U19s.

Twitter Due to your consent preferences, you’re not able to view this. Open Privacy Options

“In this generation, I don’t think colour is a big factor,” she says. “It’s nice to be from an ethnic minority and inspiring other ethnic minorities to play football, but in general just getting girls in the game to play and increasing the women’s support is a big thing.

“I think everyone’s views have changed now. We’re moving towards a more positive way of living with colour. I don’t think there’s a barrier we have to push through and try that extra bit harder to prove a point.”

What does the future look like?

To broach the subject head-on, James visited St George’s Park to ask the FA’s head of coaching Tim Dittmer about why another Black goalkeeper is yet to feature for either the men’s or women’s senior team.

The FA’s head of coaching, Tim Dittmer, says the amount of players from diverse backgrounds in the England pathway is increasing

“The players have to earn the right to come and represent and England team, so that means they have to be at a certain level in terms of their current performance or their future potential,” he says.

“Over the last 25 years, to become England No 1, that person ends up having that position for around nine or 10 years. It’s a difficult position to one, win and two, retain.

“I haven’t noticed lack of opportunity. I have seen a marked upturn in the amount of players from diverse backgrounds we’ve had in our pathway and I can see that’s definitely increasing. How that ends up playing out in senior football is the ultimate question.”

England goalkeepers with more than 10 caps since David James' retirement

- Joe Hart, 75 caps

- Jordan Pickford, 52 caps

- Nick Pope, 10 caps

Has the fact there is a dearth of Black goalkeeping coaches contributed to the lack of Black goalkeepers? Norwich goalkeeper coach Larry Raji thinks so.

“On my courses, there were none,” he explains. “I’ve been to an FA goalkeeping conference and there’s been me and [former Crewe goalkeeper] Ademola Bankole and JJ [Southend coach Jerome John] in a room of about 500 to 600 people.

“Sometimes our mentality has to change; we need to be ready to take the risk sometimes, so we’ve got to be inventive. We’re starting to see a little bit more, but it’s not enough. Nowhere near enough Black and ethnic minority goalkeepers are coming into the game now.”

Image: St George's Park in Burton-upon-Trent is the base for every England team

Scout Denva McKenzie echoes Raji’s words. “Most kids at a young age want to be strikers and score goals,” he says, speaking at Goals in Wimbledon.

“Not many people want to be goalkeepers, but those that do sometimes suffer from a lack of facility or professional coaching, so it makes it quite difficult and, in the past, it was very rare that you saw diverse goalkeepers.

“I think there’s been a lot of unconscious bias about goalkeepers in the past, but that’s part of societal issues and personal biases as well. That’s always changing, but it’s always there on an unconscious level.”

David James: The one and only – How to watch

- Sky Sports Premier League – Sunday May 14, 7.30pm

With the cost of living crisis continuing to bite, could young talent be priced out of the game?

Government data indicates 40 per cent of people that live in Black households live on a low income after housing costs (a household income of up to £14,800), compared to 47 per cent of those in Pakistani households, 55 per cent of those in Bangladeshi households and 19 per cent of White British households.

Ian Biggadike, head of the UK-wide GK Icon Academy, says the price of goalkeeping concerns him.

Datawrapper Due to your consent preferences, you’re not able to view this. Open Privacy Options

“I’m horrified sometimes when I look at some of the sites and it’s between £80 and £130 for a pair of gloves. Yes, they’re good quality, but that’s not an affordable price, especially for beginners.

“I’d say a goalkeeper goes through six to eight pairs of gloves a year and that becomes a costly process. If a child is saying to their parents they want to become a goalkeeper and then they look at the prices, it’s going to be a deterrent.”

So the big question is, how long will it take for history to change? When will we see England’s next ethnically diverse goalkeeper?

James admits he is unsure.

“It could be very soon. The frustration with everything is that, on this journey, I’ve seen so many young ethnic minority goalkeepers, male more so than female. It’s not that they’re not there. Then I also look at football and wonder if it’s football that’s racist.

“But looking at the number of English goalkeepers in top-flight football getting opportunities, there’s hardly any. So I think English goalkeepers breaking through at all is the issue.”

The journey started as David James being the one and only. How long will it be before we can say David James: The first of many?

Watch David James: The One & Only on Sky Sports Premier League at 7.30pm on Sunday May 14.

Win £250,000 with Super 6!

Could you win £250,000 for free on Tuesday with Super 6? Entries by 8pm, good luck!

Sourse: skysports.com