It wouldn’t be a World Cup without a controversy over a player crumpling with a maudlin cry of agony, clutching his shin, and plaintively pleading for mercy (and a penalty for the other team).

In the tournament’s first week, France’s Lucas Hernandez admitted to flopping in France’s 2-1 win against Australia in an attempt to get Australian midfielder Mathew Leckie sent off. Spanish defender Gerard Piqué accused Portugal’s captain Cristiano Ronaldo of exaggerating a fall to secure a penalty kick in their 3-3 nail-biter last week. Piqué said Ronaldo has a habit of “throwing himself to the ground.”

The hand-wringing over these athletic thespians is all too familiar for fans of soccer. It’s now become an infamous part of the game: the anguish. The contortion. The howls of pain. The eye-rolling. It infuriates loyalists and reinforces soccer skeptics. Some Americans frequently cite diving as unfair and unsportsmanlike, and the reason they won’t watch the World Cup.

Of course, no one who plays the gentleman’s game openly advocates for such deception, and the rules prohibit this skullduggery. Yet it remains a frequent feature on the pitch.

“I look at it as a skill,” former US Soccer phenom Alexi Lalas told the Associated Press. “There are good dives and bad dives, and the act of embellishing an action, I don’t see as an insult to the game or the person.”

Despite the (feigned) drama, there is a cold logic behind these actions. Soccer’s rules tend to favor deception, and behavioral economists have discovered just how artfully players use it to their advantage. The pros have refined diving into an artful tactic that can yield a critical edge in a highly physical contest, even when the eyes of the world are upon them.

Far from random crumples and collapses, the evidence shows players mainly take dives when it yields the maximum payoff in the game and match officials become increasingly sensitized to it.

So put on your kit because we’re about to plunge into diving in soccer.

A flop can be a decisive move in a close game

Researchers looking at diving behavior in soccer have found that players mimic patterns of deception found in the natural world. Australian biologists reported in a 2011 study in PLOS One that the closeness of a writhing player is to a referee, the “receiver” of a signal, is a key factor in whether a dive draws a penalty.

The research team found that a player flopping close to an official was three times more likely to be awarded a free kick than someone playing victim farther away. The trade-off was that being closer to a referee also made it more likely that the official would see through the ruse and ignore it — or, worse, hand out a yellow card.

The researchers watched 60 soccer matches from 10 soccer leagues and classified the kinds of falls the players made, examining whether they were tripped, got tackled, or gave an impromptu audition for a gunshot victim.

“Deception occurs when an individual benefits from signalling false information to a receiver,” the researchers wrote. “Dives are considered cost-free deceptive signals, as the cost and benefit of deception are solely dependent on how referees respond to the signal and not incurred from the production of the signal itself.”

In other words, dives are a performance for an audience of one: the referee.

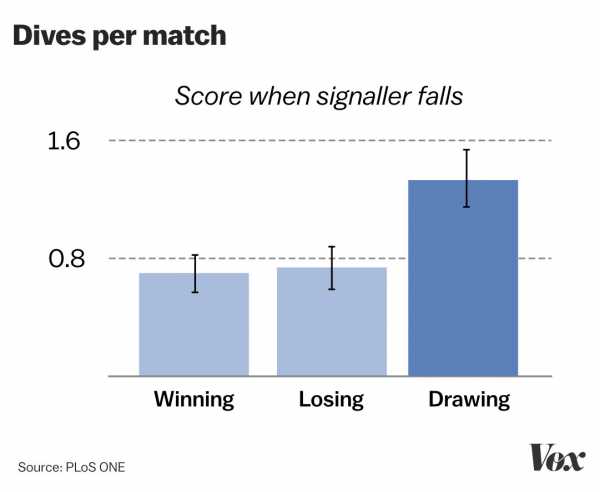

The results also showed that players were twice as likely to flop when the game was tied as when their team was winning or losing. It shows that players who hit the ground aren’t necessarily trying to burn the clock or draw sympathy so much as they are trying to gain a slight advantage against a closely matched opponent.

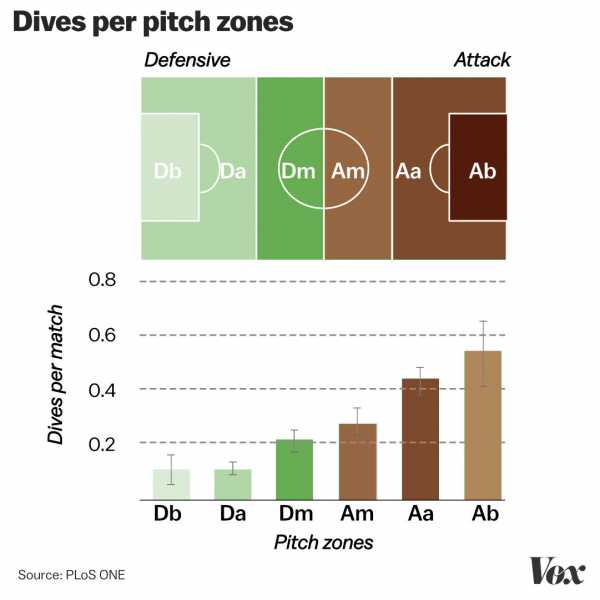

Position on the field also matters. A player was twice as likely to take a dive when attacking an opponent’s goal than when they were playing defense, and there was a steady increase in flopping behavior moving toward the goal.

So far, this pattern makes sense, but there was also a counterintuitive result: “Unexpectedly, dives were rewarded more often when they were more frequently used,” the researchers reported. And as referees awarded more penalties, players took more dives over the course of a match.

Now let’s look at a situation where this all came together:

In this 2014 World Cup game, Mexico and the Netherlands were jostling for a spot in the quarterfinals of the tournament. The game was tied 1-1 and nearing the end of regulation time when Dutch midfielder Arjen Robben drew a penalty close to Mexico’s goal.

A reasonable person could argue that Robben was, in fact, tripped by Mexican defender Rafael Márquez. But reasonable people are often wrong about many things.

This was Robben’s fifth attempt during the game to draw a foul, and he admitted after the game that some of his falls were dives. However, he maintained that the foul that resulted in a penalty kick was legitimate.

“The one at the end was a penalty; I was fouled,” Robben said. “At the same time, I have to apologise, in the first half I took a dive, and I really shouldn’t do that.”

Klaas-Jan Huntelaar squared up for the penalty kick and buried the ball in the back of the net, pushing the Netherlands through to the next round.

Everyone flops

First, let’s dispel the myth that diving is uniquely awful in soccer. All sports see a degree of exaggeration and deception, though some are more obvious than others. NBA players do it. So do NFL players. Even hockey players.

And let’s do away with the self-flattering notion that Americans are too honest to flop. Americans, the competitors that we are, deploy every tactic at our disposal, including taking dives. FiveThirtyEight ran the numbers at the last World Cup in 2014 and concluded, “This analysis doesn’t provide much support for the theory that American players don’t dive enough.”

Witness US forward Jozy Altidore’s performance at the 2010 World Cup game against Ghana, which deserves an Oscar nomination:

That’s not to say soccer players don’t spectacularly ham it up, and, of course, some countries do dive more frequently. The Wall Street Journal found that the Brazilians were the biggest drama kings at the 2014 World Cup, and the squad from Bosnia and Herzegovina was the most stoic among the 32 teams in the tournament.

The governing body of international soccer, FIFA, counsels referees to issue a yellow card when a player takes a dive. (FIFA’s term for this is “simulation.”) It’s starting to happen more in professional leagues, but players are still rarely sanctioned for flopping in international play.

US soccer’s Alexi Lalas said the crackdown “is effectively changing behavior, but robbing the game of some of its most interesting tactics.”

Why do soccer players do it anyway?

For the same reason that athletes in other sports take dives: to draw a foul. In soccer, this means a referee can stop the run of play, award a free kick, even eject the offending player. For a foul in front of the opponent’s goal, this can be a penalty kick, which is a direct shot on the goal by any player of the team’s choosing. Since the clock rarely stops and because every goal is so impactful, drawing a penalty yields a much bigger advantage in soccer than, say, free throws in basketball.

A more generous reading is that making a big show of falling can draw an official’s attention to unsporting conduct. Soccer fields are big and the game moves quickly, so it’s easy for the head referee to lose sight of a defender kicking ankles or a midfielder throwing elbows among 22 players on the field. These cheap tactics can be frustrating, but a dive and a subsequent free kick quickly tells the offender to back off.

The key factor to balance is the risk of being penalized for simulation against the reward of a favorable play call. And in many soccer leagues, the scale is tilted toward the latter.

“The code word is obviously ‘incentives,’” said Tom Vandebroek, a sports researcher in the Netherlands who now moving into professional soccer coaching. “There is no disincentive.”

Is there any way to stop diving?

The simple answer is to reverse what we discussed above: Stop rewarding it and start penalizing it. But then we have to look at the incentives for referees, who want to err on the side of caution. No one wants to be the referee who ignored a real injury or let an egregious slide tackle go unpunished, so there’s a slight bias to taking aggrieved players at their word.

“If you’re going to give a caution for simulation and there’s contact, it has to be very obvious that he’s trying to cheat,” Paul Tamberino, director of referee development for US Soccer, told the New York Times.

Some scientists have proposed using machine vision algorithms to detect flopping, but soccer is a notoriously stodgy sport. Video replays were just approved for the first time in this year’s World Cup, and even electronic goal detection remains controversial.

Others have suggested shrinking the size of the penalty box, where fouls are awarded with a penalty kick rather than a free kick. Since 1966, 81 percent of penalty kicks have been successfully converted, so another idea is moving the penalty kick spot farther from the goal to make it harder. These changes would reduce the payoff of taking a dive.

We could let the fans weigh in, but research also shows that referees are still far better at detecting fake injuries than casual observers.

For now, we just have to watch the show, however terrible it may be.

Sourse: vox.com