In a recent edition of his newsletter, the Scripps Research Institute physician and researcher Eric Topol called the BA.5 subvariant of SARS-CoV-2 “the worst version of the virus that we’ve seen.” The Washington Post used the same language in an editorial that soon followed, and earlier this week, the White House announced a strategy for managing BA.5, which stressed the subvariant’s potential to make cases rise in the coming weeks.

Why are experts so concerned about this subvariant?

For one, hospital admissions are now rising concurrently with BA.5, after several months of stable hospitalization rates. Additionally, early evidence suggests the BA.5 subvariant has features that make it better at escaping immune systems, even vaccinated ones, than its ancestors.

Also concerning: pandemic complacency has been rising alongside BA.5. Vaccine booster uptake has been modest in the US, and more than one-fifth of the population has not been vaccinated at all. Many fear that a variant better able to evade immune systems will have a better chance of reaching and harming those who remain unvaccinated.

The good news is we already have the tools to cope with a subvariant like BA.5. “It doesn’t really shake up any of our established countermeasures,” said Anne Hahn, a Yale medical school immunologist who specializes in viral evolution. That means masking and vaccines still work to prevent BA.5’s worst effects. Although, to prevent the subvariant from wreaking major havoc, people need to be willing to reengage with these preventive efforts.

Americans’ willingness to dial up preventive behaviors will determine — and, perhaps, be shaped by — the path BA.5 takes as it rises to dominance.

Is this really the worst form of the virus so far? For now, a lot remains unclear: While BA.5 has some things in common with earlier variants — the symptoms it causes seem the same, for example — scientists see a few signals that it has the potential to cause bigger problems if we don’t take some action.

The early evidence giving scientists the heebie-jeebies about BA.5

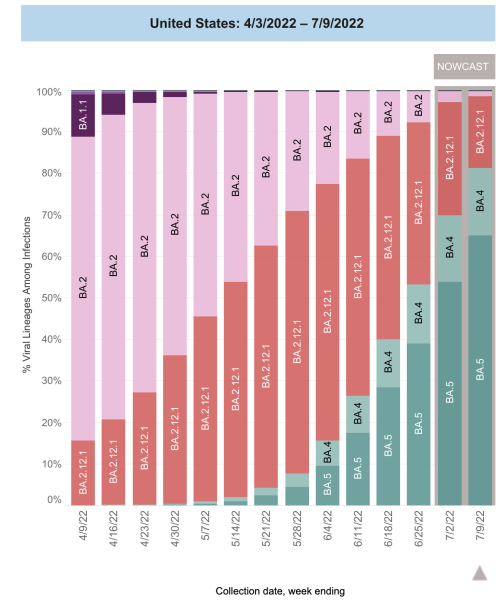

As of July 9, estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that all the SARS-CoV-2 virus currently circulating in the US is the omicron variant and its subvariants. About 65 percent of the subvariants in circulation are of the BA.5 lineage, and the proportion is rising quickly. If BA.5’s rapid expansion continues, it will likely account for nearly all US infections within a month. In South Africa, which had a combined BA.4/BA.5 wave between April and June of this year, case rates grew more quickly than did case rates of the omicron variant that preceded it.

Over the course of the pandemic, new variants have eclipsed old ones many times over — among omicron subvariants alone, BA.5 is the fifth one to rise to prominence in the US. But the first omicron wave created a massive surge in new cases and hospitalizations, while the subsequent ones did not.

BA.5’s pattern is different, and concerning: As the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants have become a larger share of the virus in circulation, case and hospitalization numbers have also begun to rise in the US.

This trend suggests BA.5 has biological advantages that previous omicron subvariants didn’t have — and laboratory data has begun to clarify what those advantages are.

A recent publication from researchers at Columbia University suggests BA.5’s genome is genetically pretty different from earlier omicron subvariants, including the one that stole Christmas last year.

Some of the differences are in the virus’s spike protein, a key target for Covid-19 vaccines. Scientists are worried that the more the spike protein changes, the less likely our current vaccines will elicit antibodies that can neutralize it. It’s possible this subvariant could lead to more infections than its predecessors, even among vaccinated people.

Epidemiological data to support this is in its early stages, but it’s highly plausible, based on some lab studies. An early-July report in the New England Journal of Medicine suggested that in vaccine-boosted people, levels of protective antibodies were three times less active against BA.5 than against the first omicron subvariants. While these antibodies are not the only way the immune system protects the body from severe SARS-CoV-2 infections (we’re looking at you, T-cells), this finding suggests vaccines could be less protective against BA.5 infection than against earlier strains.

Although Covid-19 infection has also been thought to boost protective antibody levels against new variants, omicron has changed the game. Research suggests omicron infections don’t help the immune system effectively recognize and protect against subsequent omicron infections. That makes reinfection after having an omicron variant infection more likely than reinfections that occurred after exposure to previous forms of the virus.

Real-world data from South Africa shows how this may play out in humans. BA.5 case rates in that country grew more quickly than did case rates of the omicron variant that preceded it. BA.5’s improved ability to infect people protected by vaccination and previous infection could explain its more efficient spread.

Hahn noted vaccines and, to some degree, prior infections still appear to offer good protection against severe disease due to BA.5. But there are other unknowns: several analyses have raised questions about test sensitivity for omicron subvariants, meaning some diagnostic tests might yield false negatives. There are also open questions about whether monoclonal antibodies, so far an effective treatment for previous Covid-19 variants, will be as effective against BA.5.

Overall, it appears BA.5 has clear differences to the variants that came before it. And while those differences will likely drive case increases, it’s not yet clear how deadly the wave will be.

Hospitalizations are up — but severity is not

Charts showing Covid-19 hospital admissions usually display this figure as a single line, but that line belies a lot of complexity.

For starters, most patients admitted to the hospital are screened for Covid-19, and if they test positive, they’re counted as a Covid admission — even if they’re admitted with a broken hip and are totally asymptomatic for Covid-19.

US data still does not make a distinction between so-called incidental — like the broken hip — and non-incidental Covid-19 admissions. Because of that, it’s hard to determine if the rise in hospitalizations is due to the virus growing more virulent, or if it just means it’s spreading widely in a community. During the first omicron wave — which led to asymptomatic or mild infections in many vaccinated people — some argued that hospitalization figures alone obscured a meaningful number of incidental Covid-19 admissions.

Experts sometimes use intensive care admissions and ventilator use trends in combination with local test positivity data to help understand local Covid-19 trends. Several doctors told me that judging by those criteria, they have not yet seen signs of a severe illness wave — even though US Covid hospitalizations have risen 50 percent since May.

Aaron Glatt, an infectious disease physician who is also the hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in New York, was clear: “We have not seen a surge in critical care admissions,” he said.

Although Covid-19 hospitalizations have been slowly creeping up across his region, intensive care unit admissions have stayed relatively low and stable. With incidence so high in the community, those critical care admissions and deaths are better predictors of what is really going on in some ways, Glatt said, “and those have not changed.” Glatt also said he had not noticed any new or unusual symptoms in admitted patients with Covid-19.

Susan Kline, an infectious disease doctor and hospital epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Minneapolis, said her hospital has seen Covid-19 admissions jump about 50 percent from their recent low point, and about a third of those admissions have had three or more doses of a vaccine.

However, she said, a “fairly high percentage” of people hospitalized with Covid-19 infections were admitted for reasons completely unrelated: they were only counted as Covid-19 patients because a screening test on admission was positive. In other words, she senses a large proportion of those “Covid admissions” were admitted with, but not for, Covid-19 infection.

What’s more, the patients don’t seem to be as sick as in previous waves. “In general, the patients are not showing as severe a disease as we saw early on when we were first admitting patients with Covid-19,” she said.

Even if cases aren’t very severe, a new potential big Covid wave is concerning

Even a variant that’s merely more transmissible — but not more severe — is concerning. The more people the virus infects, the greater chances it has to find the people most vulnerable to it. “The people that were at the highest risk of previously being hospitalized are going to still be at the highest risk of getting hospitalized with variants,” Glatt explained. “[Novak] Djokovic can beat me even if he’s not feeling very well,” and with any new variant, he says, “the people who are sickest, even if they’re in their best condition possible, are still going to do worse.”

Also, hospitalization and death are not the only outcome people want to avoid.

Some people with a personal “Covid-zero” policy may be motivated by concerns about long Covid — and mounting data suggests those concerns are not unfounded. A recent publication in The Lancet suggested that about 5 percent of vaccinated people infected with omicron variants developed long Covid symptoms, compared with 11 percent of those infected with the delta variant, which predominated in mid- to late 2021.

While a one in 20 chance of long Covid represents lower odds of the syndrome than in earlier analyses, the risk is still more than enough to make many want to avoid any Covid-19 infection — even one that doesn’t land them in the hospital.

Lessons from countries where BA.5 has come and gone are mixed

If there’s any reason for optimism, it can be found in countries where cases due to BA.5 have already peaked.

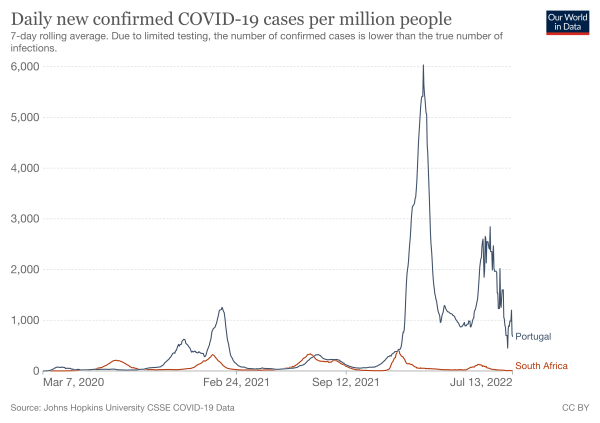

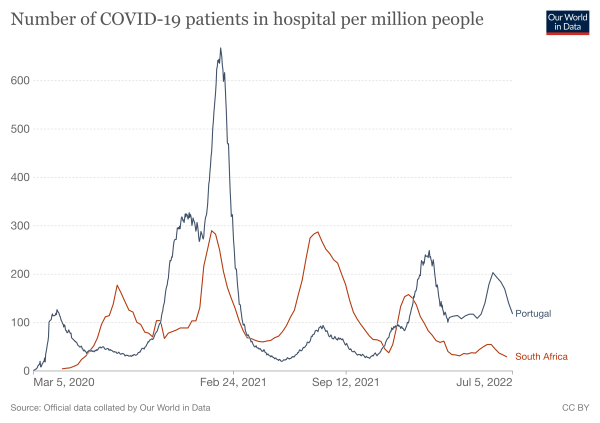

One of those countries is South Africa, where BA.5 began to rise in late March and now comprises about half of all Covid variants in the country (the remainder are mostly BA.4). During this wave, neither cases nor hospitalizations rose anywhere near as high as they were during the country’s first omicron surge last winter.

A group of South African investigators recently compared outcomes between people infected during the uptick of BA.5’s rise and those infected during earlier waves, going all the way back to the first wave in 2020.

In a publication that has not yet been peer-reviewed, the authors explained that the risk of severe illness during the more recent surge was no higher than the risk during the first omicron surge involving BA.1. They also noted that higher levels of community immunity now than at the time of the first omicron wave were likely protective against severe disease.

But the experience of other countries muddies the picture. Portugal also had a surge of cases accompanying a rising proportion of BA.5 beginning in early May, but had a different experience than South Africa’s: Hospitalizations in Portugal came much closer to the levels they reached during the nation’s first omicron wave, and its death rate has been three to 10 times higher than South Africa’s over the last few months.

Hahn said the difference between the two countries’ outcomes may be related to the difference in ages of their residents: the median age of Portugal’s population is 45, while that of South Africa’s is 28.

Additionally, Portugal had a high level of booster uptake, making their first omicron wave less severe than South Africa’s. But by the time BA.5 came on the scene, a large part of that immunity may have waned, making Portugal’s population less collectively immune than South Africa’s by the time BA.5 arrived.

The US also had a severe first omicron surge, which may mean Americans have some level of protection against a flood of severe outcomes due to BA.5. But that doesn’t mean we should welcome wave after wave of variants to keep building up immunity. “The costs are too high to really see it as a benefit,” said Hahn. “I wouldn’t say that it’s beneficial for society when people continually get sick, have work absence, and maybe even long-term implications from long Covid.”

Instead, Hahn said, we’d do well to take a little more caution when we’re faced with more immune-evasive subvariants like BA.5.

That means wearing masks when in crowded public places and getting vaccinated. And for eligible people unsure whether to get a booster dose now or wait for the omicron-specific shot expected to arrive this fall, she advises getting the additional protection sooner, even if it’s not as finely tuned. “The booster you can get now is more helpful now than the one you can get in a few weeks time,” she said.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions turn to Vox to understand what’s happening in the news. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower through understanding. Financial contributions from our readers are a critical part of supporting our resource-intensive work and help us keep our journalism free for all. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Sourse: vox.com