All of a sudden, the news seems a bit more optimistic about America’s opioid epidemic.

On Tuesday, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, who serves under President Donald Trump, pointed to new preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to suggest that the US may be “beginning to turn the tide” on the opioid crisis.

“The seemingly relentless trend of rising overdose deaths seems to be finally bending in the right direction,” Azar said at a health care conference, according to Politico. “We are so far from the end of the epidemic, but we are perhaps at the end of the beginning,” he added.

Azar’s comments followed reports by Stat and Opioid Watch pointing to recent CDC data, indicating that the deadliest drug overdose crisis in US history may be turning a corner.

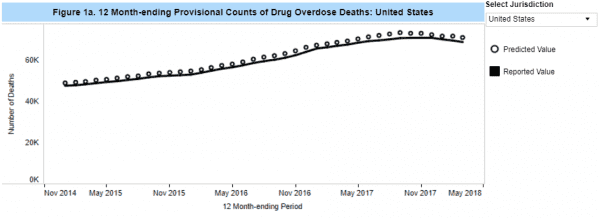

The CDC data, which goes up to March 2018, does look positive. The number of drug overdose deaths appeared to peak in September 2017, when the predicted number of overdose deaths for the previous year reached more than 73,000. But in March 2018, the predicted number of deaths over the past year had fallen — down to a bit more than 71,000. (Not all overdose deaths are from opioids, but around two-thirds have been linked to opioids in recent years.)

Here’s how that looks in chart form:

If you look at the line and dots above it, it certainly looks like the trend has slightly shifted downward. At the very least, it looks like drug overdose deaths might have leveled off.

As someone who has been covering the opioid epidemic for years now, I certainly hope this is true. But there are a few reasons I’m cautious:

1) The data is preliminary and subject to change. Overdose deaths could end up higher or lower than the data says right now. We just don’t know.

2) The recent positive trends only include six months from October 2017 through March 2018. Given that the opioid epidemic has now been building up for literally decades, this is a pretty small time frame for overdose data, and could be a blip more than a real downturn.

3) This happened before. Between 2011 and 2012, drug overdose deaths appeared to level off around 41,500. Then, highly potent synthetic opioids, particularly illicit fentanyl, seeped into the black market — and overdose deaths skyrocketed. In 2017, drug overdose deaths reached more than 72,000, based on the CDC’s preliminary data. Stanford drug policy expert Keith Humphreys said that “it’s reasonable to be cautious” about a new potential drop-off, given the past disappointments.

4) While the overall drug overdose deaths seem to have leveled off in the most recent six months of data, fentanyl deaths have continued trending up. In September 2017, synthetic opioid overdose deaths for the past year were estimated at almost 29,000. In March 2018, past-year synthetic opioid overdose deaths were estimated at more than 30,000. That’s an indication that at least one aspect of the opioid epidemic is still getting worse.

5) Fentanyl has so far mostly reached Appalachia and the East Coast, as fentanyl has increasingly been mixed with heroin on the black market or replaced heroin altogether. That’s been less likely in other parts of the country, especially the West Coast, in large part because it’s more difficult to mix fentanyl with the black-tar heroin that’s popular in the West. But that could change, said Sarah Wakeman, an addiction medicine doctor and medical director at the Massachusetts General Hospital Substance Use Disorder Initiative. If it does, overdose deaths could spike in western states, negating improvements elsewhere.

6) Overdose deaths linked to cocaine and stimulants (such as meth) have continued to trend up, according to the CDC data. They’re still not anywhere close to overall opioid deaths, but the rise may be an early warning sign of another drug overdose crisis to come. (Historically, it’s not unusual for cocaine or stimulant epidemics to follow opioid crises as people shift to other drugs.)

7) The March 2018 numbers are still worse than the March 2017 numbers, with the CDC estimating a 3.5 percent uptick in overdose deaths from the year up through March 2017 to the year up through March 2018. So although things may have improved for the better over six months, they still seem to be worse year over year.

8) Drug overdose deaths are still extremely prevalent. In 1999 (the early period of the opioid crisis), drug overdose deaths were below 17,000. They were above 72,000, or more than four times the 1999 total, in 2017. Even if deaths did level off in 2018, more than 700,000 people — more than the entire population of Boston — would die of drug overdoses over the next decade if there weren’t further declines. That should temper early celebrations.

With all of that said, there is reason to be optimistic. The painkiller and heroin numbers in particular are trending downward, pushing overall opioid and drug overdose deaths down even as fentanyl continues to tick up. The painkiller figures are a particularly good sign, Humphreys said, because it may indicate that fewer people are initiating opioid misuse and addiction through painkillers — which should lead to even better results in the long term as fewer people start misusing or get addicted to opioids in the first place.

The positive trends may be a result of some of some of the hardest-hit states getting to work on the issue. Vermont, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts in particular have taken steps to expand access to addiction treatment, particularly medications like buprenorphine and methadone that are considered the gold standard in treatment for opioid use disorder. Those states have seen drops in overdose deaths even as their New England neighbors — Connecticut, Maine, and New Hampshire, all of which have also been hit hard by the crisis — have not.

There also may be drops in overdose deaths in some Appalachian states, like Ohio and Pennsylvania, although West Virginia — which has by far the worst overdose death rate in the country — has continued to see increases in overdose deaths, based on the CDC data.

The state variation could indicate that, despite the lackluster response to the opioid crisis at the federal level, some local and state initiatives are pulling through.

Again, though, take the recent data with a grain of salt. I hope that I’m being too pessimistic. But in covering the opioid epidemic, pessimism has, sadly, served me very well.

For more on the opioid epidemic, check out Vox’s hub page for opioid coverage.

Sourse: vox.com