On February 7, Jeff Sessions, the US attorney general, was sent a letter written on the behalf of slimy creatures that have, since May, enjoyed a collective faculty appointment at Hampshire College in Western Massachusetts. The slime mold’s recommendation for Sessions was that “cannabis and its chemical derivatives should be legalized by the United States government.”

Sessions was not the only Cabinet official to receive a letter from the mold (which is technically more like an amoeba, but we’ll get to that). The slime mold also encouraged Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen to adopt an open-border policy, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt to ban offshore drilling, and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson to take a second look at food deserts.

The mold is Hampshire College’s first “nonhuman resident scholar,” complete with its own office and faculty webpage. (This very much fits in with the culture of Hampshire College, an institution that is so liberal arts it doesn’t have “majors” and that recently hosted an event exploring “the effects of mass incarceration through dance.”)

With the aid of human research assistants, the slime mold is using the problem-solving skills it acquired over a billion years of evolution to tackle policy problems. The project sits at the intersection of science, philosophy, and art. And it encourages us to consider natural forms of intelligence that exist outside the human mind.

For having no brain or neurons, slime molds — a.k.a. Physarum polycephalum — are incredibly intelligent, capable of solving complex problems with extreme efficiency. An additional plus: They’re naturally nonpartisan.

“Slime molds are not Republicans and they are not Democrats; they’re neutral; they’re other,” says Jonathon Keats, the experimental philosopher who convinced Hampshire to promote the mold to the ranks of its faculty and who penned the letters interpreting their work. “By way of observing what they do, [it] could be a way of getting out of our assumptions, out of our gridlock,” he says.

It would be a valuable perspective to have in the White House, given that the position of White House science adviser has remained vacant for the entirety of the administration. This slime mold is free.

How a slime mold thinks

Before we promote the slime mold to head the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, we need to understand its unique qualifications.

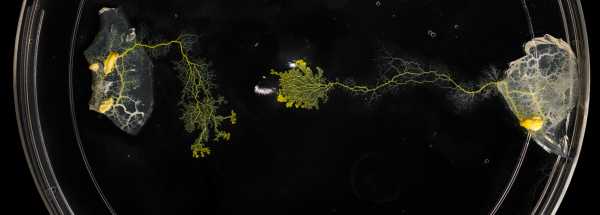

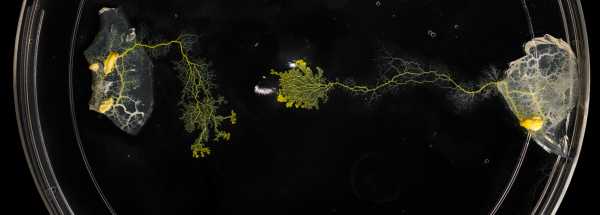

In the picture below, you can see a slime mold growing on the rotting trunk of a tree. It’s bright yellow and creates spindly, vascular-like growths that connect it to food sources.

Here’s the key to understanding the creature and its approach to problem-solving: You’re not looking at a single creature. You’re looking at many thousands of them.

Slime molds are not actually molds. They’re much more like amoebas — single-celled microscopic sacs that move around by altering their shape.

Slime molds can exist as free-floating single cells. But when two or more slime mold cells meet, they dissolve the cell membranes that separate each individual and fuse together in one membrane. That means two individuals, with individual genetics, can exist within the same body. And there’s no limit to the number of individuals that can join the collective, called a plasmodium. Each cell of the slime mold is making decisions that ultimately benefit the whole collective.

When slime molds are placed in a new environment, they’ll spread out in every direction in a fractal pattern, assessing the lay of the land. If they find something beneficial to them, like food, they’ll reinforce the pathway. If they find something they don’t like — like direct sunlight — they’ll recoil.

It sounds simple, but through this process, slime molds can solve an impressively complex array of problems.

If you spread out oats (slime molds’ favorite food) on a map, the slime molds will find ways to connect the sources of food with the shortest possible routes. If you add some obstacles to the map, like salt (which the slime mold hate), they’ll find creative ways to avoid them. When scientists model metropolitan areas in this manner, with the food representing centers of dense populations, slime mold can somewhat accurately recreate maps — like this map of the Tokyo rail system. It took human engineers years to map out the system. It took slime mold just a few hours.

But the slime molds aren’t just good at designing mass transit. Put them in a maze and they’ll trace the shortest possible map to the exit.

They also seem to teach one another. If scientists take one piece of slime mold that has solved a maze and add it to another, that second slime mold will finish the maze faster. There’s even evidence that slime mold can keep track of time.

And remember: They do this all without a brain, without a single neuron. Whatever mechanism allows slime mold to solve these problems, it’s evolved in a manner different from us. And since slime mold has been on Earth for approximately a billion years (compared to Homo sapiens’ paltry approximately 200,000), it’s a pretty useful form of intelligence and worthy of our respect, perhaps even our imitation.

Don’t bleach your colleagues

The slime molds’ “faculty appointment” at Hampshire means that they have their own office. It’s located in the basement of a science lab, “which sounds like we are degrading it, but they don’t like light,” Megan Dobro, a Hampshire College molecular biologist who works closely with the slime mold, says.

The slime mold holds office hours, and the Hampshire students who work in the lab are its research assistants (yes, they are ones assisting the slime mold). When the school held a symposium on March 1 to present the slime molds’ work, they put out wine and cheese for the human guests and oats for the slime mold.

Generally, the humans and slime mold are working well together. But there have been a few awkward moments. Normally, when Dobro experiments with microbes in a petri dish, she sprays them with bleach and throws them in the trash when finished. That’s fine for sanitizing E. coli — but it’s just a little hostile for your co-worker.

“We’ve been encouraging people to take them out into the woods and let them go free” when the slime molds’ work is through, Dobro says.

Slime mold provides a thought experiment: Would we respect alien intelligence?

Keats, the experimental philosopher who leads the project, is known for public installations that fuse science, art, and wonder. For example, in Tempe, Arizona, he’s set up a camera with a 1,000-year exposure to capture the changes in the city and landscape through the years (kind of like how night-sky photographers can capture how stars move through the sky if they set a long enough exposure). Though we’ll never live to see how the picture comes out, the project invites us to imagine how we can make sure the developed photo is not of a hellscape.

Similarly, Keats says, his project at Hampshire exists in the creative space between art and science. The overall idea, he says, is to “create an alternate reality, a parallel universe that then allows us to be able to reflect on our own.”

In this light, the slime mold is a challenge for us to consider whether we can respect the logic of other species with advanced intelligence. Imagine if aliens came down to Earth and started telling us how to better engineer sewage treatment plants. Would we listen to them? Or would we be too proud?

Closer to Earth, we could consider the slime mold to be a bit like the deep neural networks used in artificial intelligence research: These networks often come to correct answers, but they often solve problems differently than humans would.

To aid the slime molds in their policy work, Hampshire students have been setting up models of policy problems for them to work through. To model the border, petri dishes are divided in half and resources are unevenly distributed. To model drug policy, the students use valerian root, which slime molds will seek out despite the fact that it could kill them (somewhat like drug addiction in humans).

Dobro, the biologist, points out that the design of these tests, and the interpretation of them, is by no means definitive, groundbreaking science. “It’s a way to say, ‘Stop taking your emotions into consideration and look at what nature is telling you what’s good for our species.’ And that’s not a joke,” she says.

To witness the decision-making of the slime molds is to take a humbler perspective on human intelligence. “Like the slime mold, we assess our environment and make decisions — and it’s the same thing that slime mold does,” she says. “And we’re not special then; it’s just a little bit more complicated for us.”

Are we becoming a superorganism? If so, we’re pretty bad at it!

Slime mold is sometimes called a superorganism: an organism made up of organisms. The slime mold is both many and one at the same time — and therefore catnip for philosophers like Keats.

Keats understands how some might see the slime-mold professor as a gimmick (though, hey, it got me on the phone). But he sees it as an essential exercise in trying to think about, and legitimize, intelligent species other than our own. “In order for a nonhuman intelligence to be taken seriously by humans, it really is necessary it operate within human constructs, within human systems,” he says.

But it also matters in a deeper way. Keats argues humans are becoming more and more like a superorganism. Like the boundaries between two slime mold cell fusing into one, the boundaries between human societies are eroding and engulfing one another through technology. The decisions the collective “we” make, more than ever, have the potential to impact us all.

But “we’re not very good a being a superorganism,” Keats says. We’re not making collective decisions that ensure our survival. Slime molds come together to solve mazes and find creative ways to avoid salt. We come together to melt polar ice caps and perpetuate income inequality.

What if we all acted more like slime mold?

“Slime mold doesn’t have [human] bias,” Dobro reminds, “it doesn’t have politics. it’s just choosing what’s good for the whole. … Humans could act like that — for the good of the whole — but they typically don’t.”

Sourse: vox.com