Long before opioids snowballed into one of the worst public health crises in American history, Dr. Erin Krebs suspected there might be a problem.

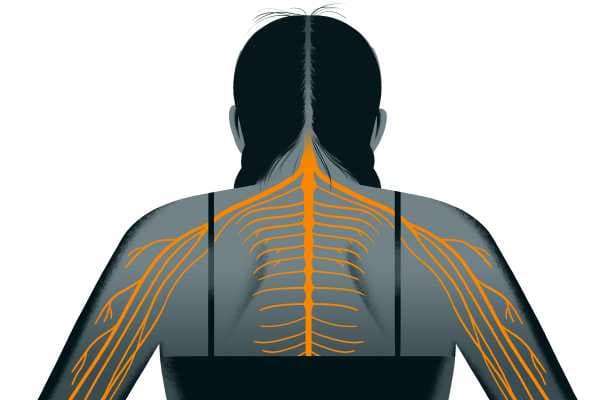

As a medical fellow in North Carolina in 2004, Krebs noticed many of her patients were on prescription opioids like OxyContin — now well known to increase the risk of addiction and death — for common ailments like low back pain and arthritis. Even after patients took the drugs for months or years, however, Krebs noticed they weren’t helping.

So she looked to the medical literature to find studies about long-term opioid use — and there weren’t any. Most trials ran for no more than eight to 12 weeks and focused on the rather useless question of whether opioids performed better than no treatment at all.

Today, opioids are still prescribed at an astoundingly high rate. But thanks to Krebs, now a researcher at the Minneapolis VA Center and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, doctors and patients will finally have a high-quality clinical trial that answers the rather simple question she’s been asking herself for more than a decade: Do opioids help patients with chronic pain in the long run? Are they worth all that risk?

The answer, according to her newly published JAMA study, is a resounding “no.”

Krebs is the lead author on the first randomized trial, comparing chronic pain patients on prescription opioids (like morphine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone) to patients on non-opioid painkillers (like acetaminophen or Tylenol, naproxen, or meloxicam), measuring their pain intensity and function over the course of a year.

The striking result was that the patients on opioids did no better than those taking the opioid alternatives — despite the much higher risk profile of opioids. At one year, the opioid takers even reported being in slightly more pain compared to the non-opioid group.

“I think this is going to shake things up,” said Roger Chou, a professor at Oregon Health and Science University who was not involved in the research. “The belief has always been opioids are the most effective pain medicine, certainly for acute pain and even for chronic pain. This [study] turns that on the head.”

“It’s not just that opioids were not better — they were a little bit worse”

It’s lately become clear that America’s opioid epidemic has been fueled mainly by heavy marketing of the drugs by pharmaceutical companies and doctors’ prescribing tendencies.

Though the overall rate of opioid prescriptions has decreased slightly in recent years, there is still an alarming quantity of opioid painkillers being doled out — many of them for chronic pain issues like low back pain. As of 2016, 67 prescriptions were being written for every 100 Americans. The same year, there were 14,500 opioid-related deaths.

All this time, doctors and patients have been operating with an incredible scarcity of high-quality evidence about how opioids work in people over the long term.

A systematic review on opioids for chronic non-cancer pain in 2006 examined 41 trials — and the average duration of the studies was only five weeks. “There’s only been one trial that’s gone out to a year, and that was a head-to-head study comparing morphine to fentanyl,” explained Chou. In other words, no long-term study has compared what opioids do to patients’ pain and how the drugs stack up against other types of treatment.

Krebs wanted to fill in that gap. For the paper, which she co-authored with colleagues in Minnesota and Indiana, she recruited 240 patients at Veteran Affairs primary care clinics who had experienced severe chronic back pain, or hip or knee osteoarthritis, for at least six months.

Related

A comprehensive guide to the new science of treating lower back pain

The researchers then assigned half of the patients to opioids and the other half to non-opioid drugs, and followed them up for a year. As a first step, the opioid group got morphine, oxycodone, or hydrocodone/acetaminophen first, and the non-opioid group tried acetaminophen (i.e., Tylenol) or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (i.e., Advil). If these prescriptions didn’t work, the doctors adjusted the patients’ medications, trying other drugs from a pre-set list.

Before the study and at three-month intervals over the course of a year, the patients scored their pain according to two main outcomes: functionality (or how easily they were able to go about their daily lives) and intensity.

At the start of the study, the opioid and non-opioid groups scored almost exactly the same on both measures. By 12 months, the groups looked indistinguishable once again on their functionality scores — they had both improved a little.

But when it came to pain intensity, the opioid group actually reported being in a little more pain than the non-opioid group at one year. What’s more, the opioid group experienced twice the number of side effects — most commonly, drowsiness, grogginess, nausea, difficulty focusing, constipation, and stomach upset.

“It’s not just that opioids were not better — they were a little bit worse,” Chou said.

“Opioids aren’t better than non-opioid medications,” Krebs summed up, “and we already knew from other research they are far more risky — and that the risk of death and addiction is serious.”

There was already randomized controlled trial evidence suggesting opioids don’t offer extra relief for patients in acute pain who came into emergency rooms. The new study now adds to the evidence that they also don’t deliver any extra benefit compared to non-opioid drugs for chronic pain patients. “You don’t want to take the riskiest possible medication when something less hazardous would work just as well — and that’s basically what we found here,” Krebs said.

Help our reporting

Hospitals keep ER fees secret. Share your bill here to help change that.

Even more remarkably, the researchers measured the patients’ perceptions of opioids: The participants in both groups in the study believe they would work better than non-opioids. Typically, the medical interventions patients believe are more potent — like surgery or an injection over taking a pill — wind up have a stronger effect. But with opioids, that still wasn’t the case. “That probably made the opioid group look better than it would’ve if [the study] had been blinded,” said Krebs.

Opioids are still being commonly prescribed — but the way we think about managing chronic pain is changing

With all the data on opioids’ harms and the absence of evidence that they help people on average, the medical community has moved away from encouraging doctors to prescribe the drugs.

In February 2017, the American College of Physicians advised doctors to prescribe “non-drug therapies” such as exercise, acupuncture, tai chi, yoga, and even chiropractics for low back pain, and avoid prescription drugs or surgical options wherever possible. In March 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also came out with new opioid-prescribing guidelines, urging health care providers to turn to non-drug options and non-opioid painkillers before even considering opioids.

The new study should bolster the guidelines, Chou said. But he also warned that it doesn’t mean opioids are never appropriate. The study is the first of its kind, and its results will need to be replicated in other settings.

“I don’t think opioids should necessarily be completely abandoned for chronic pain based on a single study done in the VA system. But I think this should have some impact on how people think about opioids for chronic pain,” he added.

Beth Darnall, a pain psychologist at Stanford University, called the study “rigorous science” but also emphasized that there are some individuals who may still benefit from opioids.

“The future is more precision pain medicine — truly characterizing each individual and having science to inform which treatment works best for each patient. We don’t yet know who is the sub-population for whom low-dose opioids may be beneficial,” she said. And until then, she warned that the pendulum shouldn’t swing too far away from opioids.

Still, America has a long way to go before the pendulum has swung too far. Medical practice changes slowly, and opioid prescribing remains rampant across the US. As of 2018, the opioid epidemic has only continued to worsen, and America is an outlier among nations for its outrageously common opioid habit. It’s not clear more or better science earlier on could have prevented the epidemic. But studies like Krebs’s should certainly make doctors think twice before prescribing the drugs.

Join the conversation

Are you interested in more discussions around health care policy? Join our Facebook community for conversation and updates.

Sourse: vox.com