The woman’s lips were blue and her skin was gray. She wasn’t getting enough oxygen.

Thirty-thousand feet in the air, the airplane staff’s resources were limited. They called over any medical professionals who happened to be onboard the Spirit Airlines flight from Boston to Minneapolis. They administered glucose and an EpiPen, but neither worked. At one point, a syringe fell out of the woman’s clothes. This was an opioid overdose.

The airplane, however, did not carry naloxone, the antidote that can reverse opioid overdoses. Staff and other passengers were forced to rely on CPR to keep the woman alive. After 25 minutes, the plane made an emergency landing in Buffalo, New York, where the woman was quickly taken to an ambulance and given naloxone. Within a minute, she was walking, Boston.com reported.

This story, from last year, exemplifies the scope of America’s opioid epidemic and how important naloxone is to fighting it. In 2016, nearly 64,000 people died of overdoses in the US, about two-thirds of which were linked to opioids — the highest number of drug overdoses for any single year in US history. Some of those opioid overdoses very well may have been reversed with better access to naloxone.

Yet naloxone remains inaccessible in many cases — often to dangerous results. Take the 2017 story: What if medical staff weren’t on-board? What if an emergency landing wasn’t an option? What if just one more person acting to save the woman’s life here — the flight attendants, the pilot, the ambulance on the ground — responded a minute too late?

A Federal Aviation Administration spokesperson told me that the agency doesn’t require naloxone in planes’ emergency medical kits, explaining that “we do not have any data to confirm adding [naloxone] to the required contents would be necessary at this time.” Currently, individual airlines decide whether to carry the drug. Spirit Airlines did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

It goes beyond airplanes. Naloxone is still limited across the country by its prescription requirement. Not all police and fire departments carry it, even though they’re often the first to respond to an overdose. And naloxone can be fairly pricey, making it difficult to ensure greater access even if a governing body wants to do so.

This has left some experts with a simple rallying cry for policymakers: Every person in the US should be able to obtain naloxone without a prescription. It should be readily available in first aid kits. We should even place it on street corners, as some cities are doing.

“It’s such a straightforward argument: Naloxone works, it reverses overdose, everybody should have it, and it should be much more available,” Corey Davis, a senior attorney at the National Health Law Program, told me.

Naloxone alone is not a silver bullet. The research on improved access to it is still early, so we don’t know just how much it could reduce overdose deaths. But more accessible naloxone would almost certainly save some lives — just like it saved the Spirit Airlines passenger.

Yet local, state, and federal policymakers still haven’t done everything they can to make this lifesaving drug accessible.

Naloxone is a lifesaving drug

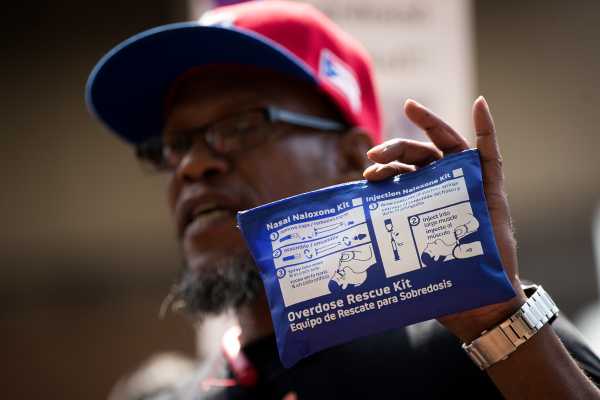

Naloxone temporarily reverses the effects of opioids such as fentanyl, heroin, and prescription painkillers like OxyContin and Percocet. It’s known by its brand name, Narcan, although there are several other brands of the drug. It’s typically applied to overdose victims through a nasal spray or injection.

Naloxone effectively pushes out and blocks off opioids from receptors in the brain. In doing this, it halts all the effects of opioids — the positive effects, such as the high and painkilling benefits, and the negative, including a potentially deadly overdose.

The effects of naloxone last for about 30 to 90 minutes, which is usually enough to stave off an overdose that could turn deadly. That not only can save a person’s life, but it also extends the opportunity to link someone to addiction treatment, such as highly effective medications like buprenorphine and methadone that are shown in the longer term to cut all-cause mortality among opioid addiction patients by half or more.

One risk: Naloxone can wear off before an overdose does. So someone could be fine while naloxone is in their system but then go back to overdosing as soon as it runs out. That’s why it’s often recommended that someone seek other emergency care quickly after applying naloxone.

Sometimes naloxone also requires multiple doses to overcome opioids. This has been reported more and more in the past few years as more powerful strains of illicit opioids, such as fentanyl and its analogs, have become more common.

While naloxone reverses opioid overdoses, it also stops the other effects of opioids. This can temporarily reverse all the painkilling benefits of opioids, bringing back someone’s pain if they’re using opioids for those reasons. And if someone is physically dependent on the drugs, it can also induce opioid withdrawal — which is often described as a mix of the worst imaginable flu, a horrible stomach bug, and hyper-anxiety.

Otherwise, naloxone has no common big side effects. Mild side effects include dizziness, tiredness, weakness, nervousness, and diarrhea.

Naloxone could help fight the opioid epidemic — but there are lingering questions

There are no good estimates for how many people are saved by naloxone each year, but it’s likely used to reverse thousands of overdoses annually.

Whether this means that expanding access to naloxone would translate to thousands more lives saved every year, however, remains unclear.

There’s certainly some suggestive research out there. A 2017 study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) found that naloxone access laws are linked to a 9- to 11-percent reduction in opioid-related deaths — which, nationwide, would add up to thousands of saved lives each year. And a 2013 study in Massachusetts found that communities with higher rates of training for a naloxone program had larger reductions in opioid overdose death rates than those with no enrollment.

But there are major questions about the research done so far. For one, these studies only establish correlation, not causation — so it’s unclear if improved access to naloxone alone is to credit for the reduced number of deaths. Experts have also raised concerns about the underlying data; studies show, for instance, that opioid overdose deaths are almost certainly underestimated — by as much as the thousands — in the US, so it’s hard to draw any reliable conclusions from analyses of opioid overdose data.

The public health experts I’ve spoken to still say that greater access to naloxone would help reduce opioid overdose deaths. The question is how big that reduction would be — or if it would even be that large of a drop.

Consider just how much naloxone demands of opioid users even if it’s easily accessible. First, opioid users would have to actually get naloxone. Then, they would have to either use opioids while someone is watching them — so a person is there to apply naloxone or call 911 if help is needed — or be stable enough during an overdose to use naloxone on themselves. And naloxone would have to be administered correctly and at the right dose.

“That’s a complex process with many opportunities to fail,” Harold Pollack, a researcher at the University of Chicago, told me.

Even if someone is saved with naloxone, that doesn’t mean that they’ll be freed from the risk of overdose forever. Police, for example, have repeatedly complained about reviving the same person multiple times with naloxone. In these cases, naloxone is essentially increasing the number of overdoses at a population level, because someone who may have only overdosed once before (and died) is now able to overdose multiple times (and live).

For public health, that’s still a better outcome than no naloxone — someone who’s revived is capable of getting treatment and going down a better path eventually, while someone who’s dead obviously isn’t. But it shows that naloxone’s ability to save a person’s life one time or more doesn’t guarantee that the person will never be at risk of a possibly deadly opioid overdose: What if police arrive too late next time? What if they’re not called at all?

So while naloxone is a lifesaving drug at the individual level, that doesn’t ensure that improved access to it would put a huge dent on overdose deaths at a population level.

Still, public health and drug policy experts broadly agree it’s worth trying — often citing improved access to naloxone as one part of a broader policy package to fight the opioid crisis, which would also include improving treatment options, reducing access to opioid painkillers while keeping them accessible to patients who truly need them, and adopting harm reduction approaches on top of naloxone, like safe injection sites and prescription heroin. Together, these policies could begin to reverse the opioid crisis.

There’s a push to make naloxone more accessible

While more could be done, states have tapped naloxone in their responses to the opioid epidemic. According to the Network for Public Health Law, every single state has enacted some sort of policy to make naloxone more accessible.

Davis, who’s a deputy director at the Network for Public Health Law, said that there are four different kinds of policies that states, counties, and cities have generally leveraged:

- Standing orders: Naloxone is a prescription medication, and prescribers can typically only write prescriptions for their own patients. Standing order laws, however, permit a prescriber to write a prescription for naloxone to be dispensed to any member of a group specified in the order, such as a person at risk of overdose or a person who might be able to use naloxone on someone who is overdosing. For example, the health commissioner in Baltimore, Dr. Leana Wen, issued a citywide standing order that effectively let anyone in the city obtain naloxone from a pharmacy or harm reduction group.

- Lay dispensing: Traditionally, only pharmacists (and sometimes other medical professionals) can physically dispense prescription medications. Lay dispensing provisions make it so others can dispense naloxone, letting more people distribute it.

- Third-party prescribing: With this policy, individuals can ask doctors to prescribe naloxone on behalf of other people who are at risk of an overdose. So a brother might ask for a naloxone prescription so he can administer it to his sister who’s addicted to heroin.

- First-responder access: First responders like police and firefighters are often the first to respond to the scene of an overdose. So some laws and policies have tried to equip these first responders with naloxone, whether by letting them administer it or by providing the funding to pay for it. Otherwise, these first responders could be forced to wait for medical services — which can take longer, increasing the odds of serious injury or death.

Not every jurisdiction has taken all of these steps. As one example: By Davis’s count, fewer than half of states have fully adopted a standing order or something similar to it.

Some places have even resisted access to naloxone. The Butler County, Ohio, sheriff, for one, has refused to let his deputies carry it, arguing that it’s the “wrong approach” to the opioid crisis.

There are other steps that individuals and community groups could take. Doctors could recommend and prescribe naloxone with opioid painkiller prescriptions or for patients with opioid use disorders. More people could carry the drug, even if they personally don’t need it. Naloxone could be packed in more — or all — first aid kits, as some airlines are now considering.

Davis has also been pushing to make some version of naloxone over-the-counter, which could eliminate the need for a prescription or standing order.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) told me that it is taking some steps in this direction, working on a model drug facts label that’s required for over-the-counter products and a simple image intended to educate consumers about how to use naloxone. But the FDA said it ultimately needs a request — from a naloxone maker or a citizen petition — with hard data supporting the switch to actually make the move.

So far, no company has filed the paperwork. Thomas Duddy, spokesperson for Narcan producer ADAPT Pharma, said that the company isn’t necessarily opposed to the idea, but it’s concerned that not enough people are educated on how to use naloxone to cut out the doctors and pharmacists who often act as the educators. Eric Edwards, vice president of innovation, research, and development at Kaléo (which produces Evzio, another naloxone product), pointed out that over-the-counter naloxone may not be covered by insurance like prescribed naloxone — although Davis argued this could be remedied with legal or regulatory changes.

Short of making naloxone over-the-counter, though, there are several steps policymakers could take — but haven’t.

Other barriers to naloxone remain

There are two big hurdles to increased access to naloxone: the price and concerns about harm reduction policies in general.

Depending on the product, naloxone can run in the tens, hundreds, or even thousands of dollars. This can make it very expensive for individuals and organizations, including police departments and harm reduction groups, trying to obtain the drug.

Insurers often cover naloxone, although they can require a copay. Adapt Pharma, Kaléo, and other manufacturers also sometimes offer discounted prices and donations.

But costs are still a commonly cited barrier, according to Davis and other experts. This is often true for drug prices in America, largely because the US does a poor job regulating its drug prices compared to other wealthy nations.

The other big barrier is the belief that expanding access to naloxone would enable more and riskier drug use. The claim: If naloxone is easily available, then would-be drug users may feel like their drug use is no longer as risky. And that might make them more likely to use drugs in general or use drugs in a riskier manner.

This is a frequent argument with all harm reduction efforts — such as needle exchange programs, even though separate studies by Johns Hopkins researchers, the World Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have found no evidence to support the idea that needle exchange programs lead to more drug use.

Similarly, there’s no strong evidence that naloxone leads to more drug use.

“There hasn’t been evidence — that I’m aware of — that suggests an increase in risk behavior,” Ingrid Binswanger, a senior investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Research in Colorado, told me. “That’s why I feel confidence as a physician prescribing it.”

Binswanger provided one reason you wouldn’t expect a trend toward riskier behavior: “Because a major adverse side effect of getting naloxone is very uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms, it’s hard to imagine why anyone would want to induce that kind of reaction. I don’t have any patients who want to go through withdrawal. So it’s unlikely that people would want to receive naloxone and not do everything they can to avoid that.”

Davis, of the National Health Law Program, drew a comparison between car safety efforts and naloxone.

“It’s the seatbelt thing,” Davis said. “Can we say that nobody drives faster than they otherwise would because they have airbags and seatbelts and so on? No, I’m relatively confident that some people do drive more recklessly because there’s all that safety stuff. Does that mean we should not have airbags and seatbelts in cars? Of course not.”

He added, “Even if somebody somewhere is going to use more or use more dangerously than they otherwise would, so what? We know that the stuff works. We know that, on net, it’s still a huge gain.”

Sourse: vox.com