In May, a United Nations panel on biodiversity released a massive, troubling report on the state of the world’s animals. The bottom line: As many as 1 million species are now at risk of extinction if we don’t act to save them.

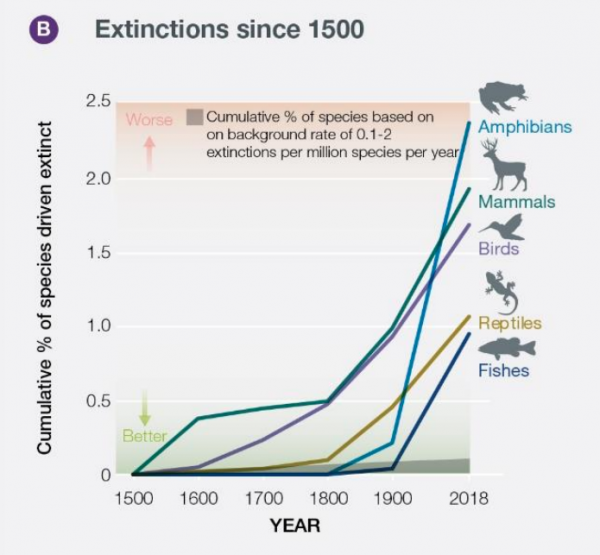

Species of all kinds — mammals, birds, amphibians, insects, plants, marine life, terrestrial life — are disappearing at a rate “tens to hundreds of times higher than the average over the last 10 million years” due to human activity, the report stated. It implored the countries of the world to step up their actions to protect the wildlife that remains — like the endangered gray wolves and caribou that roam the United States, or the threatened polar bear in the Arctic.

The Trump administration has just done the opposite.

On Monday, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced they were pushing through changes to the Endangered Species Act that will, in effect, weaken protections for species, and possibly give industry more leeway to develop areas where threatened animals live. A draft proposal of these rule changes was announced last summer. And now the rules go into effect in 30 days after they are officially published in the federal register (which the New York Times expects will happen this week).

The Trump administration’s alterations don’t change the letter of the ESA, which was passed in 1973 during the Nixon administration. But they do change how the federal government will enforce it. Here are two of the biggest changes. (Read the full new finalized rules here.)

The new rules allow for greater leeway in protecting threatened species and open the door to industry to skirt protections

Currently, species that are listed as “threatened” are defined as “any species which is likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future.” (Threatened is a designation that’s less severe than “endangered.”) The new rules constrain what is meant by “foreseeable future” and give significant discretion in interpreting what that means.

“The Services will describe the foreseeable future on a case-by-case basis,” the new rule states. Discretion is not a problem per se, but as the Washington Post explained last year, this could mean that in determining protections for plants and animals, regulators could ignore the far-flung effects of climate change that may occur several decades from now. Polar bears are threatened now, but they’ll be in even more peril in the future, when there’s less and less sea ice. There’s now more leeway for the government to determine if disappearing ice 40 years from now contributes to the threat Arctic animals face today.

The second big change is more of a giveaway to industry.

Until now, the agencies that enforce the ESA have had to base their decisions of whether to protect a species solely on scientific data, “without reference to possible economic or other impacts of such determination.”

The new rule removes that phrase. “The Act does not prohibit the [government] from compiling economic information or presenting that information to the public,” the rule argues. It does clarify that it’s allowed to do so “as long as such information does not influence the listing determination.” (But that’s confusing: Why strike the phrase from the guidelines in that case?)

That change, conservation groups fear, opens the door to business interests coming into discussions of whether a species should be protected. The new rule also gives the agencies more leeway to determine if an area that’s unoccupied by a species (but where it could also conceivably live) should be protected.

The Endangered Species Act is generally uncontroversial, and it works

The Endangered Species Act, or ESA, is the key piece of US legislation protecting wildlife. Since its passage in 1973, it’s been credited with helping the rebound of the bald eagle, the grizzly bear, the humpback whale, and many other species living throughout the US and in its waterways.

The act is generally uncontroversial among the public: About 83 percent of Americans (including a large majority of conservatives) support it, according to an Ohio State University poll. And it works: According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the act has prevented the “extinction of 99 percent of the species it protects.”

Yet the strict regulations it put in place are often frustrating (and costly) roadblocks for industries like mining or oil and gas drilling, and for developers looking to build in areas where protected species live. Ranchers routinely complain that the ESA puts an undue burden on their shoulders. Compliance with all the rules of the ESA is expensive. Environmental groups also count on the ESA as an important legal tool to block projects like coal mines.

Related

Trump’s plan to take wolves off the endangered species list is deeply flawed

These changes are part of a broad suite of policies advanced by the Trump administration to favor industries like mining and fossil fuels by limiting or scrapping the environmental protection rules they have to follow.

We’re running out of time to save wildlife

Let’s remember what’s at stake with the weakening of the ESA.

The recent UN report found that, worldwide, 40 percent of all amphibian species, 33 percent of corals, and around 10 percent of insects may be at risk of extinction.

It amounts to a biodiversity crisis that spans the globe and threatens every ecosystem. The results echo much of what we already know: Life on Earth is in peril.

Saving these animals will be a monumental task, with a scope far bigger than enforcing the ESA.

It’s going to take countries deciding to set aside more room for nature, in the form of protected areas. It’s going to take lessening the load of plastic pollution on our seas. It’s going to take addressing climate change and its various inputs. It’s going to take policies that more strongly police the import of invasive species. It means protecting indigenous communities, who use their land in a more sustainable way. It’s going to take innovation: How can we feed the increasing number of humans in the world without converting more forests to farmlands?

The report states that “goals for conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories.” If anything, the problems are accelerating.

We ought to do more to protect species — not less.

That’s because the damage we do to biodiversity in our lifetimes may never really be undone. In some ways, the fallout from the biodiversity crisis is more permanent than the climate crisis.

A few years ago, a team of researchers in Europe wanted to figure out the answer to a simple question: How long would it take for evolution to replace all the mammal species that have gone extinct in the time humans have walked the earth?

Some 300 mammal species have died off since the last ice age 130,000 years ago. The researchers estimated it would take 3 to 7 million years for evolution to generate 300 new species. Humans have been around for about 200,000 years; that’s a blink of an eye in terms of the age of the planet. Nevertheless, in that time, we have caused damage that may well last longer than our species.

And the researchers only looked at mammals. Evolution works slowly. Humans are killing off species at an alarming pace.

Sourse: vox.com