In January, Senate Republicans set their sights on a new foe in the opioid epidemic: the Obamacare-funded Medicaid expansion.

With the release of a report and an ensuing hearing, the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, led by Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI), suggested that the expansion of the public health insurance program for low-income Americans had made the opioid crisis worse.

The claim: After Obamacare encouraged states to expand Medicaid to include everyone at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (around $16,750 a year for an individual), more people obtained access to opioid painkillers, since they now could get to doctors to prescribe the drugs and had a health plan to pay for the opioids. And that may have led them to addiction or, at the very least, made opioids more available to misuse and sell in illicit markets.

But a new study published in JAMA Network Open put this claim through empirical tests — and the claim failed. In fact, the study found that the Medicaid expansion may help combat the opioid crisis by expanding or maintaining access to addiction treatment.

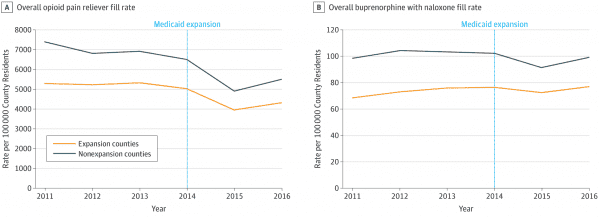

In the study, Brendan Saloner and other researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration looked at opioid painkiller prescription filling trends in three states that expanded Medicaid versus two that didn’t. The researchers also evaluated prescription fill rates for buprenorphine, a medication that’s considered, along with methadone, a gold standard treatment for opioid addiction — to see if Medicaid improved access to addiction treatment.

The researchers found that opioid painkiller prescription fill rates in Medicaid expansion counties did not significantly change when compared to non-expansion counties. And prescription fill rates for buprenorphine with naloxone (also known by the brand name Suboxone) were significantly higher in expansion counties than in non-expansion counties — although that could be more the result of a severe decrease in buprenorphine fill rates in non-expansion counties than of a dramatic increase in expansion counties.

“We looked directly at the fills for prescriptions, and we don’t really find evidence that bears out [Johnson’s] story,” Saloner told me.

In short, the Medicaid expansion did not appear to increase opioid prescribing, and it may have increased or maintained access to at least one kind of addiction treatment.

The study did find that Medicaid was more likely to pay for opioid painkillers following the expansion. But Saloner said that seemed to be a shift rather than an increase — as people now paid for the drugs through Medicaid instead of out of pocket or via private insurance.

“Prescriptions [for opioid painkillers] did fall overall. If you look at the expansion and non-expansion states, they’re trending down,” Saloner explained. “Medicaid expansion doesn’t break that trend. You don’t see them falling less rapidly in the expansion than the non-expansion states.”

Like other research, the study has limitations. It looked at only five states total, so it’s unclear if the findings can be generalized to the rest of the country. The data also does not include the past couple of years, so it can’t give us the most recent trends. And it’s hard to say if other factors influenced the prescribing rates — while the researchers tried to control for confounding variables, they’re impossible to fully rule out.

But the research is supported by other studies that have looked at Obamacare and the Medicaid expansion’s effects on the opioid epidemic. A recent study in Health Affairs, for instance, concluded that Obamacare “may have prompted state Medicaid programs to expand addiction treatment benefits and reduce utilization controls in alternative benefit plans.”

Medicaid is a solution to the crisis, not the cause

Although the supposed Medicaid expansion–opioid epidemic link was popularized in blogs and even reached the Senate, it never had good evidence behind it.

One particular issue with the idea was the basic concept of time: Medicaid didn’t expand under Obamacare until 2014 — well after opioid overdose deaths started rising (in the late 1990s), after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2011 declared the crisis an epidemic, and as the crisis became more about illicit opioids, such as heroin and fentanyl, rather than conventional opioid painkillers.

At the same time, some states have long been leveraging Medicaid to expand access to addiction treatment — including Vermont and Virginia, which have tapped federal funds and regulatory waivers tied to the public health insurance program to expand access to opioid addiction medications like buprenorphine and methadone. Studies show that the medications reduce the mortality rate among opioid addiction patients by half or more, and keep people in treatment better than other approaches.

But the claims against Medicaid persisted, wrapped in the broader context of Republican attempts to cut Medicaid and end its expansion by repealing Obamacare and tying new restrictions, such as work requirements, to the program. Linking the opioid epidemic to that cause, given that the epidemic is now the deadliest drug overdose crisis in US history, was an attempt to give Medicaid cuts a positive argument.

The new study, however, suggests that if Republicans cut Medicaid, they likely do so at the cost of making addiction treatment less accessible — and therefore would make the opioid epidemic worse, not better.

Still, that doesn’t mean Medicaid is perfect or doing as good of a job as it could be, Saloner cautioned. “There’s room for improvement,” he said. With addiction treatment, “there’s pockets of innovation happening. We’re nowhere near a full-scale national model for how to do this effectively.”

For more on how some states are using Medicaid to fight the opioid epidemic, read my in-depth report on Virginia.

Sourse: vox.com