The white supremacists marching at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, last year were not ashamed when they shouted, “Jews will not replace us.” They were not ashamed to wear Nazi symbols, to carry torches, to harass and beat counterprotesters. They wanted their beliefs on display.

It’s easy to treat people like them as straw men: one-dimensional, backward beings fueled by hatred and ignorance. But if we want to prevent the spread of extremist, supremacist views, we need to understand how these views form and why they stick in the minds of some people.

It’s important because they’re not going away. This weekend in Washington, DC, a second Unite the Right rally will convene. No one is really sure how many white nationalists will attend, or if the counterprotesters will greatly outnumber them. But they plan to meet in front of the White House to once again put their beliefs on proud display.

Last year, psychologists Patrick Forscher and Nour Kteily recruited members of the alt-right (a.k.a. the “alternative right,” the catchall political identity of white nationalists) to participate in a study to build the first psychological profile of their movement. The results, which were released in August 2017, are just in working paper form and have yet to be peer-reviewed or published in an academic journal.

That said, the study uses well-established psychological measures and is clear about its limitations. All the researchers’ raw data and materials have been posted online for others to review. Meanwhile, Forscher and Kteily are working on an extended, more rigorous version of the survey, which will pull from a nationally representative sample of Trump voters. (Read more about their plans here.)

So while last year’s survey is a preliminary assessment, it validates some common perceptions of the alt-right with data. It helps us understand this group not just as straw men but as people with knowable motivations.

A lot of the findings align with what we intuit about the alt-right: This group is supportive of social hierarchies that favor whites at the top. It’s distrustful of mainstream media and strongly opposed to Black Lives Matter. Respondents were highly supportive of statements like, “There are good reasons to have organizations that look out for the interests of white people.” And when they look at other groups — like black Americans, Muslims, feminists, and journalists — they’re willing to admit they see these people as “less evolved.”

But it’s the degree to which the alt-righters differed from the comparison sample that’s most striking — especially when it came to measures of dehumanization, support for collective white action, and admitting to harassing others online. That surprised even Forscher, the lead author and a professor at the University of Arkansas, who typically doesn’t find such large group difference in his work.

There was a time when psychologists feared that “social desirability bias” — people unwilling to admit they’re prejudiced, for fear of being shamed — would prevent people from answering such questions about prejudice truthfully. But this survey shows people will readily admit to believing all sorts of vile things. And researchers don’t need to use implicit or subliminal measures to suss it all out.

How Forscher and Kteily surveyed the alt-right

In April 2017, Forscher and Kteily got a sample of 447 self-identified alt-righters in an online survey on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (an online marketplace for gathering study participants and people for quick paid tasks) and led them through a barrage of psychological survey questions. They then compared the alt-righters to an online sample of 382 non-alt-righters. (See the demographic breakdown of the samples here.)

A note on some limitations: This survey was not designed to be representative of the entire “alt-right” movement or to generalize to other right-wing-leaning groups. It’s a convenience sample of alt-righters on the internet who were willing to take a survey for a small cash reward.

Even so, it’s instructive. The people who answered this survey are people who stood up and identified as alt-right, similar to the marchers in Charlottesville, and similar to those who are expected attend the August 11 rally in DC. Even if this survey only represents a small portion of the people who adhere to this ideology, it’s useful for understanding exactly how they are distinct as a group and what’s behind their divisive views.

Here are some of the biggest differences between the alt-right and control group the researchers found.

The alt-right scores high on dehumanization measures

One of the starkest, darkest findings in the survey comes from a simple question: How evolved do you think other people are?

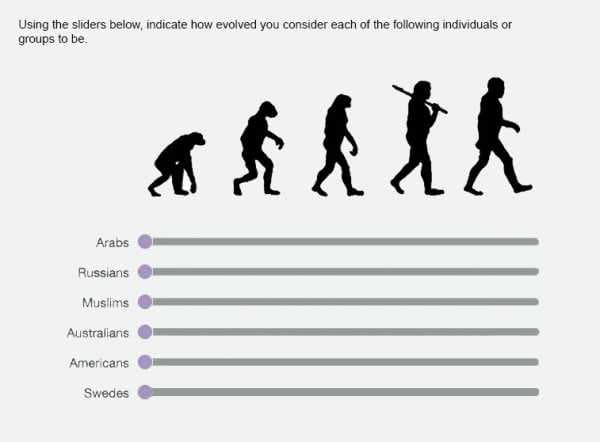

Kteily, the co-author on this paper, pioneered this new and disturbing way to measure dehumanization — the tendency to see others as being less than human. He simply shows study participants the following (scientifically inaccurate) image of a human ancestor slowly learning how to stand on two legs and become fully human.

Participants are asked to rate where certain groups fall on this scale from 0 to 100. Zero is not human at all; 100 is fully human.

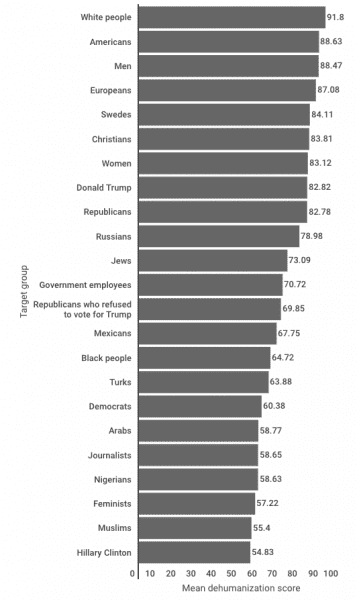

On average, alt-righters saw other groups as hunched-over proto-humans.

On average, they rated Muslims at a 55.4 (again, out of 100), Democrats at 60.4, black people at 64.7, Mexicans at 67.7, journalists at 58.6, Jews at 73, and feminists at 57. These groups appear as subhumans to those taking the survey. And what about white people? They were scored at a noble 91.8. (You can look through all the data here.)

The comparison group, on the other hand, scored all these groups in the 80s or 90s on average. (In science terms, the alt-righters were nearly a full standard deviation more extreme in their responses than the comparison group.)

“If you look at the mean dehumanization scores, they’re about at the level to the degree people in the US dehumanize ISIS,” Forscher says. “The reason why I find that so astonishing is that we’re engaged in violent conflict with ISIS.”

Related

The dark psychology of dehumanization, explained

Dehumanization is scary. It’s the psychological trick we engage in that allows us to harm other people (because it’s easier to inflict pain on people who are not people). Historically it’s been the fuel of mass atrocities and genocide.

The alt-right has high support for groups that support and work for the benefit of white people

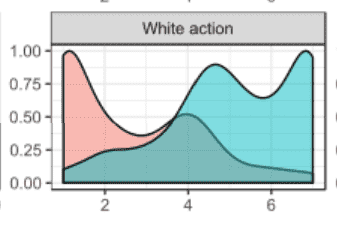

This is — unsurprisingly — the largest difference Forscher and Kteily found in the survey. They asked participants how much they agreed with the following statement: “I think there are good reasons to have organizations that look out for the interests of whites.”

And the differences between the alt-right and the control sample were about as big as you could possibly find on such a survey. The average difference was 2.4 points on a 1-to-7 scale. That’s nearly a full 1.5 standard deviations. “In my work, I’ve never seen a difference that big,” Forscher says.

Here’s what those distributions look like plotted. The green on the right represents the answers of the alt-right. The red on the left represents the comparison group. They’re mirror images.

The alt-right wants and supports organizations that look out for the rights and well-being of white people. Historically, such groups have done so by striking fear in the hearts of immigrants, Jews, and minorities.

The alt-right is more willing to express prejudice toward black people

These survey questions ask respondents the degree to which they agree with statements like, “I avoid interactions with black people,” “My beliefs motivate me to express negative feelings about black people,” and, “I minimize my contact with black people.”

Again, these questions showed huge differences. Forscher explains it like this. When he runs these questions on samples of college students, he usually sees average scores around 2 (out of 9, meaning people largely don’t agree with these questions.) “In the alt-right samples, I’m seeing numbers around 3 or 4, relatively close to the midpoint. In all the samples I’ve worked with, I haven’t seen means at that level.”

In other words, members of the alt-right are unabashed in declaring their prejudices.

Alt-righters are willing to report their own aggressive behavior

The survey also asked participants to state how often they engaged in aggressive behaviors, like doxxing, the releasing of private information without a person’s permission. They also asked about how often respondents physically threatened another online, or made offensive statements just to get a rise out of people.

Here, too, the alt-righters were much more likely to admit to engaging in these behaviors.

“In the comparison sample, people basically never did those things, or reported [doing them],” Forscher says. But it wasn’t like the alt-righters were uniformly admitting to these behaviors.

“We found evidence that there’s a much more extreme group of [alt-right] people who are reporting harassing and being offensive intentionally,” he says. He calls them “supremacists.”

“But there’s a group of people who doesn’t do that that much, or not that much at all,” he says. Forscher and Kteily label this less extreme group “populists.” They’re less aggressive and dehumanizing overall, and more concerned with government corruption. But even these milder “populists” are as supportive of collective white action, and as opposed to the Black Lives Matter movement, as the supremacists.

Personality traits that frequently show up among alt-righters: authoritarianism and Machiavellianism

Alt-righters in the survey scored higher on social dominance orientation (the preference that society maintains social order), right-wing authoritarianism (a preference for strong rulers), and somewhat higher levels of the “dark triad” of personality traits (psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism.)

Alt-righters aren’t particularly socially isolated or worried about the economy

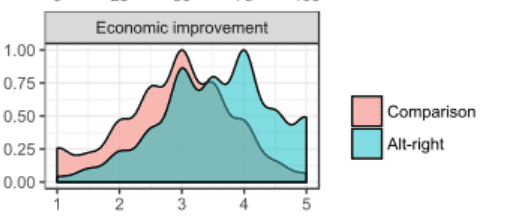

Among the measures where the alt-right and comparison groups don’t look much different in the survey results is closeness and relationships with other people. The alt-righters reported having about equal levels of close friends, which means these aren’t necessarily isolated, lonely people. They’re members of a community.

Also important: Alt-righters in the sample aren’t all that concerned about the economy. The survey used a common set of Pew question that asks about the current state of the economy, and about whether participants feel like things are going to improve for them. Here, both groups reported about the same levels of confidence in the economy.

What’s more, “the alt-right expected more improvement in the state of the economy relative to the non-alt-right sample,” the study states (perhaps because their preferred leader is president).

It goes to show: The alt-right is motivated by racial issues, not economic anxiety.

But it goes deeper than that. The survey revealed that the alt-righters were much more concerned that their groups were at a disadvantage compared with the control sample. The alt-right (and white nationalists) is afraid of being displaced by increasing numbers of immigrants and outsiders in this country. And, yes, they see themselves as potential victims.

Knowing the psychology of the alt-right may be the key to stop white supremacist views from spreading

This is the quixotic hope behind a lot of social science research: The first step to solving a problem is defining the nature of that problem.

Once we understand the psychological motivations behind the alt-right worldview, maybe we can learn to stop it.

This survey is just a first step in that direction. “One of the biggest reasons I wanted to do this in the first place was to find some leverage points for change,” Forscher says. If we know, for instance, that alt-righters rapidly dehumanize others, we can turn to the psychological literature on dehumanization for clues to stage interventions (or prevention).

In their preliminary analysis, Forscher and Kteily found that willingness to express prejudice against black people was correlated with harassing behavior. “If we can change the motivation to express prejudice, maybe that gives us a way to prevent aggression,” they say.

Again, this is all early work. Forscher hopes to track some of these survey participants over the coming months and years, and see if they remain adhered to the alt-right. Or if not, he hopes to learn what caused them to ditch the worldview.

“When we’re thinking about current events, our thinking should be grounded in evidence rather than intuition,” he says. “This provides some evidence. It’s definitely not the be-all and end-all.”

Sourse: vox.com