If you’re wondering when you can start eating all the romaine lettuce again without fear, the answer is: hang tight.

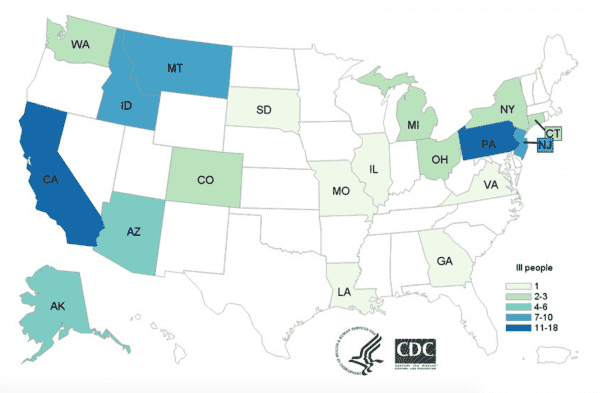

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with the Food and Drug Administration, are still searching for the source of E. coli-contaminated romaine lettuce, which has sickened 84 people across 19 states over the past two weeks. Of these cases, half have been hospitalizations, including nine people who developed kidney failure.

“Do not eat or buy romaine lettuce unless you can confirm it is not from the Yuma, Arizona, growing region,” the CDC warned on Wednesday. And that includes all types — from heads and hearts of romaine to chopped romaine and romaine used in salads and salad mixes.

But in reality, we should probably be a little wary of lettuce all the time — not just when there’s a big E. coli outbreak. As sales of precut and bagged greens have boomed, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: They’re now one of the most common sources of food poisoning in the US.

One in six Americans get sick from food — many of them from salads

Some 48 million people (one in six Americans) get sick from the food every year. Of those, about 128,000 wind up in hospitals and 3,000 die. And the foods most frequently implicated here are probably not what you think.

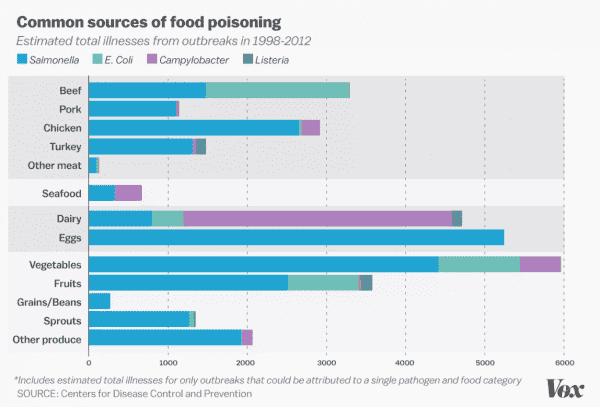

According to a 2015 estimate from the CDC, nearly half of all food-borne illnesses are caused by produce. Meanwhile, dairy and eggs cause 20 percent, meat and poultry are the culprits in only 22 percent of cases, and fish and shellfish just 6 percent.

A 2013 analysis by CDC of food poisoning cases between 1998 and 2008 found that leafy vegetables — salads and the like — caused almost a quarter of all food poisonings. That was more than any other food product, including dairy and poultry. Leafy vegetables were also the second most common cause of food poisoning-related hospitalizations.

“Back in the ’90s and early 2000s, E. coli cases linked to hamburgers represented almost all that I did,” said Bill Marler, one of America’s leading food safety attorneys. “Now it’s none of what I do. Now it’s just salads, raw vegetables.”

Michele Jay-Russell, a food safety researcher at the University of California Davis who has investigated salad-related poisoning outbreaks in the past, said the raw vegetables that are the most common culprits are basically all salad greens, but especially the chopped and bagged kind. “We really haven’t seen kale and some of the other greens [with contamination] problems, at least not yet. And romaine is one of the most common lettuce products that are used in salads.”

Why fresh produce is now a major source of food poisoning

So more people are now sickened by leafy greens than by their hamburgers or sushi. And there are a number of different drivers of this trend.

People are simply eating more fresh produce these days than they did just a few years ago. This means there’s more risk of exposure to pathogens that may be hanging out in fruits and veggies. (In a Washington Post’s story about the E. coli outbreak, one of the people who fell sick from the contaminated lettuce was a 16-year-old from Wilton, California, who had been eating salads every day in a bid to be healthier.)

And we tend to eat most produce raw. That means “there’s no kill step for the consumer to cook off the bacteria that might be lurking in our food,” said Jay-Russell.

There are many different strains of E. coli, and most of them live in our guts and don’t cause any harm. But the strain that’s led to the outbreak now — E. coli O157 — produces toxins that are dangerous for humans. The bacteria are typically transmitted from animals to humans through animal excrement that has contaminated food or water. The symptoms of infection include cramping, vomiting, diarrhea, and, rarely, kidney failure and death.

While there are extensive procedures to prevent this kind of food poisoning from happening, and regulations on farms have gotten stricter, some contamination can still slip through.

Some of the processes farms have in place to clean salads actually trap bacteria in the plants, making them impossible to wash away. “During harvest, workers core lettuce in the field, often with a knife soiled by pathogen-laden dirt,” explained Modern Farmer in an article about why lettuce keeps sickening people. “The plant then produces a milky latex that essentially traps any present pathogens in the plant.”

But contamination can happen “all along the spectrum of growing plants,” Jay-Russell added. “There can be animal intrusions or inputs like contaminated water sources that bring the bacteria into the field.”

There are also types of bacteria that you simply can’t wash off, or the contamination happens in places you typically don’t splash with water, like inside the core of a lettuce head. That can make it pretty hard to prevent food poisoning, even with the triple washing most bagged lettuces go through.

Our love of convenient, prepackaged salads amplifies the risk

Marler also blames Americans’ love of convenience for the problem. “Mass-produced chopped, bagged lettuce that gets shipped around the US amplifies the risk of poisoning,” he said.

Instead of shipping heads of lettuce or large carrot sticks that people wash, we chop them and mix them up in processing, then package them in plastic bags. In that process, Marler said, “The bacteria has a chance to grow. And a lot of people get sick.”

This prepackaging makes it harder to find the cause of a food poisoning outbreak. Different lettuces grown at different farms get mixed into bags that are distributed at supermarkets and restaurants all over the country, so food safety officials need to search for the common link among suppliers.

“When it gets processed, you might have four to five farms supplying the processor on any day. So was it farmer one, two, three, or four that was contaminated?” Marler asked. It also means that when something goes awry in a batch, it can cause a very widespread problem — like the one we’re seeing now.

“In a perfect world, nobody would mix and match lettuce so this problem wouldn’t happen,” he said. “I think the [question] is: Is the convenience worth the risk?”

Sourse: vox.com