The World Health Organization has declared the growing coronavirus outbreak in China to be a global health emergency. It’s a recognition that the outbreak — now with nearly 10,000 cases — may continue to spread beyond China, and that the nations of the world should lend their assistance and be prepared.

Just a month ago, this virus, called 2019-nCoV, was unknown to science. Now, health officials are working furiously to understand it, trying to prevent a pandemic (a larger global spread of an infection).

These are still early days. Critical questions about the virus — namely how it spreads, and how deadly it is — remain to be firmly answered. But it’s not too soon to wonder: How does this outbreak end?

Right now, infectious disease experts are outlining three broad scenarios for the future of this outbreak. Keep in mind there’s a lot of uncertainty about how this will unfold.

1) The spread of the virus gets under control through public health interventions

This is the best-case scenario, and essentially what happened with the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak in 2003.

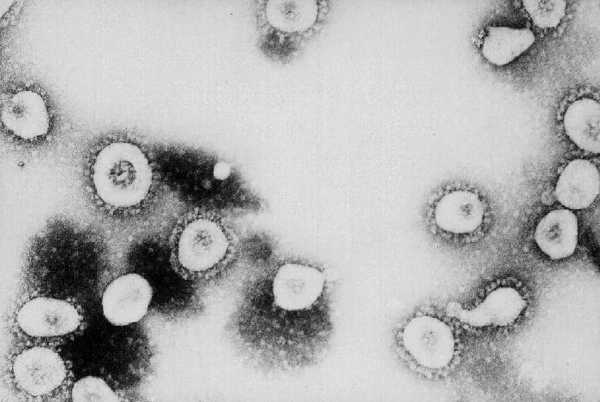

SARS, like this new virus, is also a coronavirus — a group of viruses that cause disease in mammals and birds. There several known coronaviruses that infect humans; others infect animals.

SARS mainly infects animals, but can jump to humans and start spreading among them. In late 2002 and 2003, SARS infected 8,096 people (mainly in China), and killed 774 people in 17 countries.

Remarkably: By 2004, SARS was basically gone. “SARS was the classic case of how various public health interventions can work and stop an outbreak,” Jessica Fairley, a professor of global health medicine at Emory University, explains.

During SARS, health authorities all worked toward identifying cases as quickly as possible, and putting infected people in isolation. That way, their immune systems can fight the virus without it spreading to anyone new. (In the unlucky cases, the virus will kill the patient, and it goes down with them.)

This takes a lot of coordination: Physicians looking out for the virus, good investigations into every case to find out who they came into contact with, and tight infection control measures in hospitals. ”And then you have more of the bigger things: travel restrictions, quarantines, or screening people at airports,” Fairley says.

It all happened fast. SARS was first reported in February 2003. By March, hundreds of people who have been exposed to SARS are quarantined in their homes. Travel advisories to the most affected areas were posted by the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, airports started screening international travelers, asking them questions about symptoms and whether they had any possible contact with the virus. And concurrently, doctors were getting more and more vigilant about diagnosing the disease, and getting patients into isolated care. By midsummer, many of the countries that had seen outbreaks were declared SARS free.

These days, SARS may still exist in animals. But it’s not spreading in humans.

Unfortunately, it might be hard to repeat the success of controlling SARS with this new outbreak. SARS was somewhat easier to contain. For one, infected people typically didn’t spread the disease until they were showing symptoms, like a fever. That means once a person got sick, they could be taken care of in quarantine, and transmission would stop there.

“If [SARS] cases were infectious before symptoms appeared, or if asymptomatic cases transmitted the virus, the disease would have been much more difficult, perhaps even impossible, to control,” a 2006 WHO retrospective on the outbreak said.

With the new outbreak, scientists are still figuring out whether the virus can be spread before symptoms arise. (Researchers now report one case where the virus was spread in this manner.) But if it can, that will make it harder to control, since some people won’t know they’re sick and may not seek medical care.

Also, in the case of SARS, health officials were a bit lucky as “it was not very efficient at transmitting outside of health care settings, and without the aid of superspreaders,” says Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Superspreaders are rare carriers who, due to either their behavior or makeup of their immune system, are disproportionately responsible for spreading disease. With SARS, once these people were identified, and put in isolation, it was easier to stop the disease. With the new virus, it’s not yet known what role superspreaders play.

What is known: The new outbreak is already larger than SARS. A new mathematical model published in The Lancet estimates that up 75,800 people could have been infected as of January 25 in the Chinese city Wuhan where this outbreak originated, noting that “some of those infected may be undercounted in the official register.” The researchers suggest that if the transmission of the virus is reduced by a quarter, the outbreak’s growth rate would slow.

Ultimately, an outbreak can also end with the invention of a new vaccine: But even in the fastest scenario, that could take years. “So it really comes down to how good individual public health agencies are at detecting cases, getting them care, putting them into isolation, and how good the people who are infected are at their own hygiene,” Nathan Grubaugh, an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health, says.

2) The virus burns itself out after it infects all or most of the people most susceptible to it

Disease outbreaks are a bit like fires. The virus is the flame. Susceptible people are the fuel. Eventually, a fire burns itself out if it runs out of kindling. A virus outbreak will end when it stops finding susceptible people to infect.

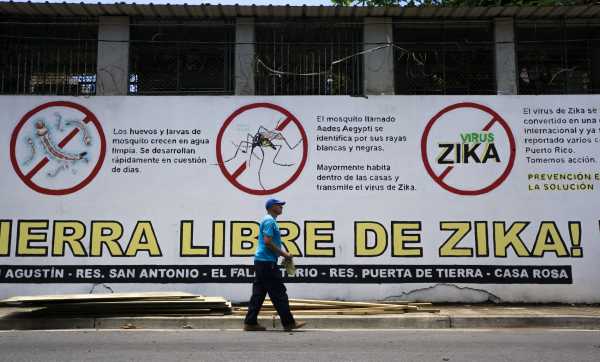

Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health, offers the 2015-2016 Zika virus epidemic in Puerto Rico and South America as an example of an epidemic that essentially burned itself out. “Tons and tons of people got infected very rapidly,” he says. (There were more than than 35,000 cases in Puerto Rico in 2016.) But then the number of people susceptible to the disease dwindled. Those who were most at risk of coming into contact with the disease-carrying mosquitoes already got the disease. “And that ultimately leaves fewer people for those viruses to go in and infect.”

Zika is still circulating to a smaller degree in Brazil. But in Puerto Rico, officials report, it’s not really spreading anymore.

With the new coronavirus, it’s still hard to how it might burn out on its own. That’s because “we don’t totally know exactly who is susceptible” to the virus, Mina says. There could be people with more of an immunity to it that others — which would limit its reach. Also once the outbreak does begin to naturally burn out, public health authorities might have an easier time stamping it out with quarantines and screenings.

It’s also possible that the virus could largely burn out in China, while good surveillance keeps it from taking hold in other countries.

This isn’t a desirable scenario. It will involve many more people getting sick, possibly dying. How bad it would be depends on aspects of the disease officials are trying to understand: how many people who catch the infection get sick, how many of those people die, and how easy is it to spread from one person to the next.

“Usually with outbreaks there’s a peak, and then it comes down,” Fairley says. “The question will be if we’ll able to completely control it, or if there will be ongoing transmission.”

Which brings us to …

3) Coronavirus becomes yet another common virus

There’s a third scenario about how this outbreak ends. That it doesn’t.

This has happened before. In 2009, a new strain of the H1N1 flu virus encircled the globe in a pandemic. But, “after a while it became a part of our normal repertoire of what might come up each flu season,” Mina says.

Adalja explains there are now four coronavirus strains that commonly infect humans as common colds or pneumonia. It’s possible that this virus becomes the fifth — and like the flu, it could come and go with the seasons. Possibly, it could become a seasonal virus in China. Or, it could, like the flu, envelop the whole world.

“It may be that our policies have some impact on containing this outbreak” outside of China, he says. “In China, it may become a seasonal coronavirus.” Though, he stresses “it’s hard to say what’s going to happen.” This is just a possibility.

It’s also not a great one. Humanity doesn’t really need another common virus to contend with. “It does seem to have some capacity to cause severe disease,” Adalja says. “It’s not just causing common colds. We have people that have died from it. We have people in ICUs — all of that makes it something you want to get a handle on. It doesn’t quite seem as severe as SARS but it definitely seems more severe than the other coronaviruses that we’re used to dealing with every year.”

Sourse: vox.com