Lee Tomlinson wasn’t a smoker. He wasn’t a drinker. He was a longtime professional tennis player and marathoner based in Los Angeles, “the healthiest guy anyone knew,” he says.

That’s why, in 2012, at the age of 62, he was shocked to learn that he had stage-three throat cancer.

Until fairly recently, most oropharyngeal cancers — cancers of the back of the throat, the tonsils, and the base of the tongue — mainly showed up in people who smoked and drank heavily, and usually quite late in life.

But Tomlinson’s illness was caused by something else: human papillomavirus, or HPV, a sexually transmitted infection that can be genital or oral.

As a young athlete traveling the world, Tomlinson — who’s now 68 and still recovering from cancer treatment — said he had his share of sexual dalliances with women. But he had no idea this youthful experimentation, and oral sex in particular, could lead to cancer. He had no symptoms and hadn’t even heard of HPV until he was staring down his diagnosis.

While public health campaigns about STDs have helped to dramatically reduce HIV rates and improve condom usage, many Americans are still ignorant about the risks of HPV. It’s the most common STD in the country that will infect almost every sexually active person at some point in their lives — and one of a few that can cause cancer.

As we’ve shifted toward having more partners and more oral sex, HPV-related cancer cases are creeping up, while HPV vaccine rates are lagging.

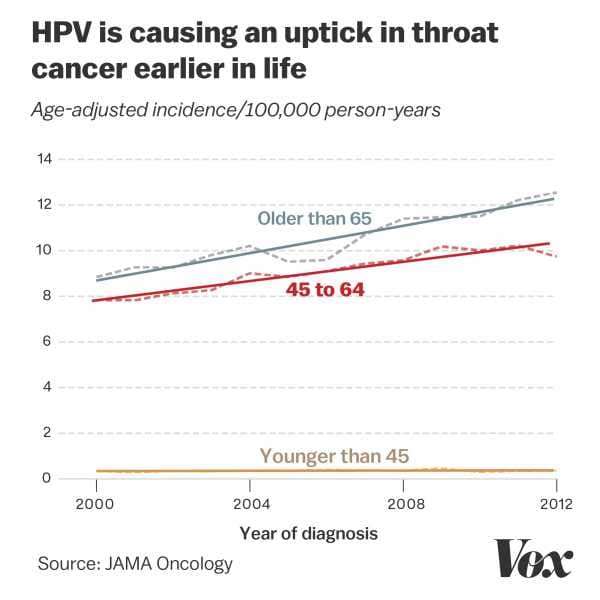

One of the most worrisome developments is HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers in middle-aged men, like Tomlinson. Between 1999 and 2015, this kind of cancer increased 2.7 percent per year among men and 0.8 percent per year among women. Many of the men who get cancer this way say they had no clue they had the virus, or that it put them at risk.

Other HPV-related diseases like genital and anal cancers in men and women are on the rise, too. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of new HPV cancers reported annually went up from 30,115 in 1999 to 43,371 in 2015. HPV now causes nearly all cervical cancers, 95 percent of anal cancers, and 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancers.

There are more than 200 strains of the virus. Most are considered low risk, with little chance of leading to cancer. But 14 “high-risk” strains can cause oral or genital cancers.

And the prevalence of those dangerous HPV types is high. According to an April 2017 CDC report, one in four men and one in five women in 2013 to 2014 had a high-risk strain of genital HPV, while one in 25 men and women had a high-risk strain of oral HPV. (Not everyone who has one of these strains will develop cancer.)

The good news is that most of these high-risk strains are targeted by the HPV vaccine. The shots have already been shown to prevent cervical cancer, and new evidence is emerging that shows that it can prevent oral cancers (like Tomlinson’s) too. That’s why doctors are now calling the HPV vaccine “one of the most significant cancer prevention tools ever developed.”

Yet too many Americans are still wary — or unaware — of the vaccine. It’s recommended for boys and girls ages 9 to 26, but only six in 10 girls and half of boys get the shot. That’s much lower than the uptake of other routine vaccinations — such as the polio or measles-mumps-rubella vaccines — which typically hovers around 80 or 90 percent.

To Tomlinson, the opportunity to prevent oral or genital cancers should be a no brainer for parents and young people. “There are parents who don’t inoculate their kids because they think it’ll make them more promiscuous. I ask them: ‘Would you rather your kids be sexually promiscuous or would you rather they be dead’?” Tomlinson said. “It’s a simple choice.”

How the sexual revolution ushered in the HPV era

Since the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the advent of the birth control pill, Americans have been experimenting with sex at younger ages, and with more sexual partners, increasing their risk of sexually transmitted infections like HPV.

They’ve also been having more oral sex across age groups as the taboo around it has diminished. Today, teenagers report having oral sex more frequently and having vaginal sex less frequently than teens before them — in part because they believe that oral sex is safer.

What’s missed with that strategy is that HPV can be spread quite easily through sex, even when condoms are used, and especially through condom-free oral sex.

Michael Douglas became the de facto poster-child for HPV when, in 2013, he famously said his throat cancer “came about from cunnilingus.” There was more uncertainty back then about the link, but researchers who study and treat oral HPV cancers now say it’s clear: This is a new disease trend that’s being driven by our sexual habits.

“We think HPV as the cause of [oropharyngeal] cancers is probably due to changing sex practices — specifically oral sex,” said Ben Roman, a head and neck surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York.

The people who came of age during the sexual revolution, like Tomlinson and Douglas, were the first demographic group to experience the rise in HPV-related oropharynx cancers in their middle age, which is why researchers think oral sex is the main culprit here. Having HPV in the oral cavity gives people a 50-fold increase in risk for HPV-positive head and neck cancers.

As this group has aged, HPV-related head and neck cancers have followed them — but it’s also reaching younger people, even those in their 40s.

“When we started looking at this about 10 years ago, we were seeing the increase was most prominent at younger ages,” said Anil Chaturvedi, an NIH researcher who studies the epidemiology of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer.

Now, when researchers like Chaturvedi look at the data, they find HPV-related oral cancer is increasing in both the less than 60 years age group and in older groups as well — the people who are most likely to have had oral sex.

What we know about people who get HPV-related cancer

Since the 1980s, the percentage of HPV-related oropharynx cancers has been steadily increasing — and HPV is now the cause of the vast majority of tumors found in the oropharynx. At the same time, as smoking rates have declined, the incidence of oropharynx cancers that are not caused by HPV has dropped off dramatically.

To put that into clearer terms, HPV-negative oropharynx cancers dropped by half between 1988 to 2004, while HPV-positive oropharynx cancers increased by 225 percent.

Altogether, HPV infections are now causing about 43,000 cancers in men and women each year, according to the CDC. Cervical cancers are most common among women, and oropharyngeal cancers are the most common among men.

For people who didn’t smoke, the three-year survival odds for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers are high — around 90 percent. The odds of survival for cervical and anal cancers are similarly good when they’re caught early.

There are a couple of things we know about the people who get HPV-related cancers: They tend to have a high number of oral sex partners over their lifetime, and they also tend to be male and white. (Both HPV infection and related cancers are about three to five times more common in men than women.)

Researchers haven’t been able to figure out why men are more susceptible, but suspect it might be caused by the fact that women’s immune system seem to be able to ward off the virus’ cancer causing properties more readily.

Roman said that in his practice, he still sees more men than women with oropharyngeal HPV cancers, and they tend to be middle aged. Because the virus doesn’t cause any symptoms (unless genital warts are involved), the discovery tends to be a surprise. “The usual story is that a man was shaving and they felt a lump in their neck, and they went to primary care doctor and got antibiotics,” he explained. If the drugs don’t work, they eventually get a biopsy and HPV test, and often find out they have cancer.

Why only about half of Americans who should get the HPV vaccine are getting it

America lags behind other industrialized nations when it comes to HPV vaccine uptake. A major reason for the lag is that some parents are concerned about the vaccine’s safety — even though there’s no good data suggesting significant safety concerns. And it doesn’t help that politicians and popular media figures, like Michelle Bachman and Alex Jones, fearmonger about the shot.

In most states, the vaccine isn’t required for school entry, like the polio or measles-mumps-rubella vaccines is. According to the American Cancer Society, only Rhode Island, Virginia, and DC have HPV vaccine requirements in place (and Puerto Rico also has also recently added it to the list of routine shots).

There’s also hesitancy among doctors to recommend the vaccine, in part because of the sexual stigma around it. Yet the CDC reported that a doctor’s suggestion to get an HPV vaccine was strongly associated with a teen getting immunized, which is why oncologists are working on a rebranding effort for the vaccine to encourage pediatricians and family doctors to more forcefully recommend the immunization.

“Vaccination shows the greatest promise,” Chaturvedi said when I asked him about how we’ll bend this cancer curve. He expects that in two or three decades, as the first groups of children who were immunized against the virus reach middle age, we’ll see oropharyngeal cancer rates decline and thousands of HPV-related cancer deaths averted.

After three months of chemotherapy, and 35 radiation treatments between July and December 2012, Tomlinson still has sores in his mouth, and perpetual pain in his tongue. But he’s through the worst — the months when he could hardly speak at all, or when the pain of swallowing saliva “was like swallowing broken glass.” At those moments, he says he wanted to die.

If he had had the chance to avoid that pain with a vaccine, he would have happily taken it. Refusing a cancer-preventing shot, he says, “is lunacy.”

Clarification: A previous version of this article stated that HPV is the only STD known to cause cancer. In fact, Hepatitis B and C and HIV are also known to raise the risk of cancer.

Sourse: vox.com